Manuscript accepted on :25-03-2022

Published online on: 30-03-2022

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. David Crompton

Second Review by: Dr. Tahmineh Mokhtari

Final Approval by: Dr. Ian James Martin

Sagayaraj Kanagaraj1* Kinjari Kancharla1

Kinjari Kancharla1 , C. N. Ram Gopal1

, C. N. Ram Gopal1  and Sundaravadivel Karthikeyan2

and Sundaravadivel Karthikeyan2

1Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Chettinad Hospital and Research Institute, Chettinad Academy of Research and Education, Kelambakkam, 603103, Tamil Nadu, India.

2Department of Clinical Psychology and Medical Science, National Institute for Empowerment of Persons with Multiple Disabilities, Chennai, 603112, Tamil Nadu, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: harrysagayaraj@gmail.com

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/2385

Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects individual social communication with a range of restricted behaviour patterns. People with ASD will also have difficulties with social emotional reciprocity, which is not predominantly found in neurotypical individuals. Individuals with ASD have difficulty connecting with neurotypical (i.e., nonautistic) people because they fail to identify other people's emotions and mental states. Alexithymia is a personality characteristic defined by a subclinical inability to identify and explain one's own emotions. Alexithymia is defined by a significant dysfunction in emotional awareness, social attachment, and interpersonal relationships. It is distinguished by impaired emotional awareness, which has been increasing in diagnostic frequency in a variety of neuropsychiatric diseases, with notable overlap with ASD. To empirically measure the condition of alexithymia in neurotypical individuals (N = 12) and people diagnosed with ASD (N = 12), were assessed with the Observer Alexithymia Scale (OAS) by Haviland et al., 2000. The mean age of the neurotypical is (M = 21.67; SD = 2.60) and the ASD is (M = 18.33; SD = 2.22). Using SPSS ver.20, the data was analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics methods. The results indicate the significant difference between neurotypical and autism spectrum disorder individuals with the condition of alexithymia. The path model, which was drawn from the SPSS AMOS version 20, emphasises the causal relationship between variables of interest from the Observer Alexithymia Scale. This study found that individuals with ASD have significant corroboration to alexithymia when compared to neurotypical individuals.

Keywords

Alexithymia; Autism Spectrum Disorder; Emotional Expression; Emotional Reciprocity; Neurodevelopmental; Neurotypical

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Kanagaraj S, Kancharla K, Gopal C. N. R, Kathikeyan S. Neuropsychological Approach on Expressed Emotion in Neurotypical and Autism Spectrum Disorder : A Path Model Analysis. Biomed Pharmacol J 2022;15(1). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Kanagaraj S, Kancharla K, Gopal C. N. R, Kathikeyan S. Neuropsychological Approach on Expressed Emotion in Neurotypical and Autism Spectrum Disorder : A Path Model Analysis. Biomed Pharmacol J 2022;15(1). Available from: https://bit.ly/3JUseXH |

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is commonly referred to as a pervasive developmental disorder, which indicates that it occurs in early childhood and affects many aspects of a child’s development. However, there is now a growing understanding that autism should not be considered as a condition but rather as a neurological diversity. This is why the terms “neurodiverse” and “neurodivergent” are used to refer to ASD 1. The revised diagnosis criteria for ASD are included in an update to the World Health Organization’s manual, “International Classification of Disease – eleventh revision (ICD-11)”. Autism, asperger syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) are all classified as ASD in the most recent version of the ICD-11 manual. Similar to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), the ICD-11 divides ASD symptoms into two categories: difficulty with social communication and social engagement; and repetitive or restricted pattern of behaviour 2. People with ASD, in particular, have been considered challenged by their capacity to understand other people’s viewpoints or attribute mental states to other people (often referred to as mind-blindness or a lack of theory of mind) and to have a lack of empathy. There is now a lot of evidence that ASD is largely caused by neuro-biological abnormalities and difficulties. That is, the typical social, communicative, and repetitive behaviours associated with autism are the developmental outcomes of a brain that is fundamentally wired and structured differently 3.

Alexithymia is a personality trait that causes difficulty recognising and reacting to emotions in oneself or others. However, the symptoms of alexithymia are not as severe as those associated with conditions such as ASD. Alexithymia is usually related to various mental health issues and developmental disabilities, most notably ASD. The difficulty in recognising, perceiving, or reacting to emotions is a distinguishing characteristic of alexithymia. This can lead to issues with empathy, difficulties with conflict resolution, and many people with alexithymia also struggle in their relationships with partners, friends, and family 4.

Researchers do not know the aetiology of Alexithymia. It is most probably the result of a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Children with alexithymia are more likely to have difficulty expressing socially acceptable emotions. Children who do not develop a constant connection with others or an understanding of feelings are more likely to struggle with emotional awareness later in life, because alexithymia frequently co-occurs with other mental health disorders. Individuals who develop the ability to perceive, explain, and react to emotions may experience less alexithymia symptoms and have fewer interpersonal relationship difficulties 5.

Individuals with high alexithymia scores have difficulties recognising and contextualising their internal emotional states, discriminating between numerous forms of the same subjective emotion, and communicating their emotional states to others. These people also have fewer imaginal processes and think in a stimulus-bound, externally focused manner (i.e., concrete thinking). Alexithymia is not a psychiatric diagnosis and of itself; rather, it is a three-dimensional personality trait that occurs to varying degrees in the general population and is linked to a number of medical, mental, and psychological issues 6-10. The purpose of this research was to get a thorough knowledge of alexithymia and to compare it to those who are normally developing and those who have ASD. This comparative research will look at the outcomes of expressed emotion, which includes recognising, perceiving, and regulating emotion in neurotypical and people with ASD.

Materials and Methods

Hypothesis

H0 There will be no significant difference between neurotypical and autism spectrum disorder individuals in the condition of alexithymia.

Sample Descriptions

A total of 24 participants took part in this study which include (Neurotypical N = 12), (Autism Spectrum disorder = 12). The mean age of neurotypical is (M = 21.67; SD = 2.60) with (Male N = 5; Female N = 7). The mean age of autism spectrum disorder individuals is (M = 18.33; SD = 2.22) with (Male N = 8; Female = 4). The participants from the autism spectrum disorder group were already been clinically diagnosed with the Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA) 11 and found to have mild and moderate levels of autism from the assessment.

Tools Used

The Observer Alexithymia Scale (OAS) by Haviland et al., 2000.12 (33 items) was used to collect information from the participants. It is a 4-point likert scale ranging from 0 = never; 1 = sometimes; 2 = usually; and 3 = all of the time. The scale has a test-retest reliability of (rtt) = 0.87 and an internal consistency of Cronbach alpha ranging from 0.88 to 0.89. The scale is validated with exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The scoring was computed as per the manual of the OAS. Higher the score indicate the high level of having the alexithymia condition.

Procedure

It is an observer measurement scale, so the acquaintances or relatives of the participants were asked to rate the subjects who took part in the study. The participants were informed about the purpose and significance of the study. Also, their anonymity and confidentiality were protected.

Ethical Consideration

This study was carried out with the approval of the Institutional Human Ethics Committee of Chettinad Academy of Research and Education (216/IHEC/Nov/2020), Kelambakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India as a part of supporting the doctoral research.

Data Analysis

The analysis of the collected data was computed using descriptive statistics mean (M), standard deviation (SD); and inferential statistics independent t test by using SPSS ver 20. The path model was drawn by using SPSS AMOS Ver 20.

Results and Discussion

While the current study’s goal is to empirically investigate the expressed emotions of neurotypical and autism spectrum disorder participants, other factors such as social background, economic background, and gender differences were not taken into account. Table 1 indicates the gender and age-wise details of the neurotypical participants from the study. It consists of male participants (N = 5; Age M = 21.81; SD = 2.41) and female participants (N = 7; Age M = 21.14; SD = 2.45). Table 2 indicates the gender and age-wise details of the autism spectrum disorder participants from the study. It has male participants (N = 8; age M = 18.15; SD = 2.34) and female participants (N = 4; age M = 18.00; SD = 1.58).

Table 1: Details of the Neurotypical Participants in Percentage

| Gender | Percentage | |

| Male | 5 | 42% |

| Female | 7 | 58% |

| Age | ||

| 18 years | 1 | 8% |

| 19 years | 2 | 17% |

| 20 years | 2 | 17% |

| 21 years | 1 | 8% |

| 22 years | 2 | 17% |

| 24 years | 2 | 17% |

| 25 years | 1 | 8% |

| 26 years | 1 | 8% |

Table 2: Details of Autism Spectrum Disorder Participants in Percentage

| Gender | N | Percentage |

| Male | 8 | 67% |

| Female | 4 | 33% |

| Age | ||

| 16 years | 2 | 17% |

| 17 years | 3 | 25% |

| 18 years | 3 | 25% |

| 19 years | 1 | 8% |

| 20 years | 2 | 17% |

| 24 years | 1 | 8% |

Table 3: Comparison between Neurotypical and Autism Spectrum Disorder Participants

| Mean | SD | T-Value | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | 95 % Confidence Interval of the Difference

Lower Upper |

||

| Neurotypical | 33.08 | 9.33 | 15.7* | .000 | 33.08 | 27.15 | 39.01 |

|

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

78.66 | 3.67 | 78.66 | 76.33 | 81.00 | ||

From Table 3, it was found that the Observer Alexithymia Scale (OAS) score of the neurotypical participants was (M = 33.08; SD = 9.33) and the autism spectrum disorder participants (M = 78.66; SD = 3.67). It is found that the independent sample t-test value of 15.7 is statistically significant at the 0.05 level, so the hypothesis that there is no difference between neurotypical and autism spectrum disorder people with alexithymia is false hence rejected. This means that there is a significant difference between neurotypical and autism spectrum disorder people with this condition. The capacity to perceive and comprehend emotional expressions on others faces is a basic skill in daily interactions, and it is especially essential early in life, before the onset of language 13. Face recognition is a key cue for social interaction and emotional communication. Facial expression recognition appears to develop gradually from birth and childhood and appears to persist into early adulthood 14. As a neurotypical person who has been exposed to various emotional cues throughout their childhood and neurological condition, they are wired in such a way that they can identify and perceive the emotion in a variety of ways. Because of the neuro developmental condition, people with ASD have a hard time understanding social and emotional cues.

|

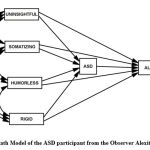

Figure 1: Path Model of the ASD participant from the Observer Alexithymia Scale. |

ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder

Alexithymia : Condition assessed by the Observer Alexithymia Scale Haviland et al., 2000

The domain distant from the observer’s alexithymia scale is completely negatively scored, hence the neurotypical participants scored less when compared to ASD participants. The items were positively assessed in nature but negatively scored for interpretation. Hence, in the path analysis model, the significant correlation of the domains such as uninsightful, somatizing, humorless, and rigid was presented in the figure 1.

Table 4: Neurotypical and Autism Spectrum Disorder participants scores based on the Observer Alexithymia Scale.

| Domains

(Total N=24; Neurotypical N = 12 and Autism N = 12) |

Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

| Distant | Neurotypical | 11.5833 | 4.66044 | 1.34535 |

| Autism | 29.0000 | 1.27920 | .36927 | |

| Uninsightful | Neurotypical | 9.3333 | 3.14305 | .90732 |

| Autism | 18.5000 | 1.62369 | .46872 | |

| Somatizing | Neurotypical | 5.0833 | 2.96827 | .85686 |

| Autism | 12.2500 | 1.65831 | .47871 | |

| Humorless | Neurotypical | 2.9167 | 2.39159 | .69039 |

| Autism | 11.0833 | 2.35327 | .67933 | |

| Rigid | Neurotypical | 4.3333 | 1.92275 | .55505 |

| Autism | 7.8333 | 1.58592 | .45782 | |

| Total | Neurotypical | 33.0833 | 9.33671 | 2.69528 |

| Autism | 78.6667 | 3.67630 | 1.06126 | |

In table 4, it was shown that persons with autism scored higher than neurotypical individuals in all aspects of the OAS. Uninsightful denotes an inability to perceive things deeply or, depending on the context. Somatization is the process through which psychological problems become physical symptoms. Things that are excessively serious, unsmiling, or unable to recognise humour are referred to be humourless. The inability to adjust or adapt one’s body language or facial expression is referred to as rigidity. All of these dimensions conceptually mirror the clinical state of alexithymia, which has been shown to be considerably higher in ASD patients.

|

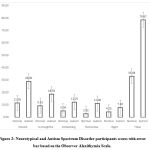

Figure 2: Neurotypical and Autism Spectrum Disorder participants scores with error bar based on the Observer Alexithymia Scale. |

Figure 2 represents the domain wise responses of the participants and the total mean score of the OAS. Error bars provide a broad notion of how accurate a measurement is, or, conversely, how distant the real (error-free) value may be from the reported value.

Conclusion

The research experimentally showed that there is a statistically significant difference between neurotypical and autism spectrum disorder people in emotional expression. When compared to neurotypical people, individuals with ASD are more prone to conditions such as a lack of emotional expression, being uninsightful, somatizing, being humourless, and rigidity. Persons with autism spectrum disorder are more likely to have alexithymia than neurotypical people, according to the findings.

Limitations

The number of participants in our research was limited since we were only interested in comparing ASD patients to non-ASD patients. In this research, we didn’t compare cognitive or behavioural functioning, which are two additional fundamental aspects of human functioning.

Acknowledgment

The corresponding author would like to thank and acknowledge former Prof. Dr. R. Murugesan, Director-Research, CARE and Prof. Dr. O. T. Sabari Sridhar, Head-Department of Psychiatry, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research for their valuable suggestions and support during the course of the work. He also extends his sincere gratitude to the Department of Clinical Psychology, National Institute for Empowerment of Persons with Multiple Disabilities (Divyangjan) for their constant support and cooperation throughout the study.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding Source

Chettinad Academy of Research and Education, Junior Research Fellowship (CARE – JRF) fund.

References

- Kapp S.K, Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement. Palgrave Macmillan, ; Springer (2020).

CrossRef - World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems.;(11th ed.) (2019).

- Volkmar F. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Hoboken, New Jersey.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (2014).

CrossRef - Fitzgerald M, Molyneux G. Overlap Between Alexithymia and Asperger’s Syndrome. American Journal of Psychology.; 161(11):2134-2135 (2004).

CrossRef - Poquérusse J, Pastore L, Dellantonio S, Esposito G. Alexithymia and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Complex Relationship. Frontiers in Psychology. 9:1196 (2018).

CrossRef - Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. Twenty-five years with the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Res;131:109940 (2020).

CrossRef - Westwood H, Kerr-Gaffney J, Stahl D, Tchanturia K. Alexithymia in eating disorders: systematic review and meta-analyses of studies using the Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Res;1(99):66–81 (2017).

CrossRef - Kajanoja J, Scheinin NM, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Karukivi M. Illuminating the clinical significance of alexithymia subtypes: a cluster analysis of alexithymic traits and psychiatric symptoms. Journal of Psychosomatic Res;1(97):111–7 (2017).

CrossRef - Hadji-Michael M, McAllister E, Reilly C, Heyman I, Bennett S. Alexithymia in children with medically unexplained symptoms: a systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research.;123:109736 (2019).

CrossRef - Berardis DD, Campanella D, Nicola S, Gianna S, Alessandro C, Chiara C, et al. The impact of alexithymia on anxiety disorders: a review of the literature. Current Psychiatry Reviews.;4(2):80-6 (2008).

CrossRef - Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. Scientific Report on Research Project for Development of Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism.; New Delhi: Government of India; 2009.

- Haviland MG, Warren WL, Riggs ML. An observer scale to measure alexithymia.Psychosomatics.; 41(5):385-92 (2000).

CrossRef - Leppänen JM, Nelson CA. Tuning the developing brain to social signals of emotions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.;10:37-47 (2009).

CrossRef - Somerville LH, Fani N, McClure-Tone EB. Behavioral and neural representation of emotional facial expressions across the lifespan. Developmental Neuropsychology.;36:408-28 (2011).

CrossRef