Mugdha Deshpande and Devaki Gokhale

Symbiosis School of Biological Sciences Symbiosis International Deemed University Taluka: Mulshi, District: Pune-412115

Corresponding Author E-mail : devakijgokhale@gmail.com

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1949

Abstract

Undernutrition is a major cause of disability preventing children from reaching their full development potential due to various reasons like poor infant and child nutrition, suboptimal caregiver-child interaction. Assessment through infant and young child feeding practices (IYCF) based on breastfeeding practices recommended by WHO is of utmost importance as they directly influence child growth. Thus the aim of the study was to assess the knowledge, attitude and practice of infant and child feeding among lactating mothers from rural areas of Nanded, Maharashtra. A cross-sectional study was conducted among 141 mothers and their children aged less than 2 years across 4 Anganwadi centres using structured interviews and systematic random sampling. The purpose of the study was explained and informed consent was obtained on voluntary basis. A total of 90.1% of the women knew WHO recommendation on breast milk to be the first feed that should be consumed by the child after birth and complementary feeding to be initiated after 6 months. Majority of mothers (90%) had a positive attitude about breast-feeding their child on demand but almost a quarter of them (24.8%) had a lesser positive attitude. 79.4% children were breast-fed within an hour of their birth and 87.2% of children were exclusively breast-fed for the first six months of life. A quarter (25%) of women had good IYCF practices. It was observed that although women were aware of the IYCF and its importance, there were barriers to put it to practice. Hence, need further development towards behaviour change communications intervention strategies to bridge the gap between what is known and what is practiced through community health workers.

Keywords

Attitude; IYCF; Infant; Knowledge Practises

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Deshpande M, Gokhale D. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Infant and Young Child Feeding among Lactating Mothers from Rural Areas of Nanded, Maharashtra. Biomed Pharmacol J 2020;13(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Deshpande M, Gokhale D. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Infant and Young Child Feeding among Lactating Mothers from Rural Areas of Nanded, Maharashtra. Biomed Pharmacol J 2020;13(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/2M9Micv |

Introduction

Infant and Young Child feeding (IYCF) practices are the practices which focus on early initiation of breast feeding (within one hour after birth), exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months (180 days), introduction of home-made energy dense complementary feeds only after 6 months, continued breast-feeding for at least 2 years, use of World Health Organization (WHO) growth charts for monitoring growth of child and communication of mother with the child during feeding. Appropriate Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practices are essential for optimal growth, cognitive development, and overall well-being in early vulnerable years of life1–3 .

Growth stunting and severe muscle mass wasting together are responsible for 2.2 million deaths 4. An estimated 32%, or 186 million, child below two years of age in developing countries are stunted and about 10% or 55 million have muscle mass wasting. The new NFHS-4 data for 15 states including Maharashtra showed that 37% of children under age of five in these states are stunted, a fall of just five percentage points occurred in a decade. There are 200 million children under the age of 2 who fail to reach their cognitive developmental potential due to various reasons like poor infant and child nutrition and suboptimal caregiver–child interactions5. This supports that following correct feeding practices is not only beneficial for the child’s nutritional status, but also his developmental skills 6.

Unless massive improvements in child nutrition are made, it will be difficult to achieve millennium development goals which state eradication of extreme poverty and hunger and reduction in child mortality 7. The 2008 Lancet Nutrition Series on maternal and child malnutrition also covered the importance of optimal IYCF on child survival 4. There have been various studies demonstrating the association of IYCF practices and reduction in maternal mortality rate, infant mortality rate and related morbidities8–13

Knowledge, attitudes and practices associated with infant and young child feeding forms an essential first step for an intervention program designed to bring about positive behavioural change in infant health along with the assessment of infant feeding indicators by WHO14,15.IYCF practices including, breast-feeding are a direct factor influencing child survival, growth, development, intellect and sustenance16. Hence, their assessment is of utmost importance. The lack of evidence especially in Nanded district, on simple indicators of appropriate feeding practices in children aged 0-2 years has hampered progress in measuring and improving feeding practices thereby limiting improvements in infant and young child nutritional outcomes17

Materials and Methods

Study Locale

The study was conducted in the rural areas of Nanded District: Vishnupuri, Kalhal, Markand, Kaleshwar and Khupsarwadi. The data collection was performed in the recognized Anganwadi Centres of these villages. Here, occupations of women were limited to doing household chores at others houses like washing utensils, clothes, cleaning and dusting, etc., one of the participant had just started a small business from home of selling western tops and Indian kurtis, and about 2-3 were nurses in a Government Hospital nearby. The five areas were approximately 2-3 miles apart.

Sample Size

The data was collected for a sample size of n=141, calculated using formula [n= [[Z [1-α/2]2] X p X [1-p]]/d2] with 38% as the prevalence of undernutrition in Maharashtra, 95% confidence level and 8% degree of desired precision.

Data Collection Procedures

The data collection was conducted in a classroom at an Anganwadi center at Vishnupuri, Kalhal, Markand, Kaleshwar and Khupsarwadi. Instructions were given to the Anganwadi workers to help conduct the data collection process by calling women and children to the Anganwadi center on a given date and time. Objectives of the study were explained and those who voluntarily agreed to participate were taken through the consent processes. Possible benefits and/or risks of participating in the study were explained. Data was collected via interview method using structured questionnaires following completed consent forms.

Inclusion Criteria

Mothers of disease-free children in the age group of 0-2 years of age were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Mothers of children above the age group of 0-2 years, or children suffering from any abnormal genetic condition or metabolic syndrome were excluded from the study.

Data Collection Tools

The data was collected using three forms:-

Form A- Socio Demographic Data

This questionnaire had two sections, part one was information about the mother. It included her name, current age, age at last pregnancy and number of children she had conceived in the past including the current child. Part two contained information about the child. It included child’s name, age and parity.

Form B- KAP Questionnaire

This questionnaire was adapted from the standardized questionnaire of Food and Agriculture Organization FAO.

This questionnaire was used to assess knowledge, attitude and practices of women towards Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices. It was adapted from KAP Questionnaire by WHO on Infant and Young Child Feeding Practice. The questionnaire was divided into three parts: Knowledge, Attitude and Practice. Part one included questions about knowledge on exclusive breast feeding- its meaning, reasons, advantages to the mother and child, duration of breast feeding, frequency of feeding and reasons for initiating complementary feeds after six months. The second part included questions on attitude of mothers towards exclusive breast feeding and difficulty in feeding management. In addition, questions about attitudes of mothers towards expressing, storing and feeding the same milk to the child were also included. The last part included questions on practices such as type of food consumed by the child before 6 months, inclusion of complementary foods after 6 months. Upon completion the end, knowledge and practice score of participants was also calculated. For knowledge score, a scoring out of 11 was done. Score of 9-11 was considered as excellent, 7-8 as good and <7 as poor. Similarly, for practices, scoring out of 3 was done, 1 being poor, 2 being good and 3 being excellent.

Form C- IYCF Indicator Questionnaire

This questionnaire was adapted from the standardized questionnaire of WHO, 2010.

There are eight feeding indicators set by WHO and United Nations International Childrens Emergency Fund (UNICEF) for assessing compliance of population to Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices. These indicators are close ended questions with three options of “yes”, “no”, and “don’t know”. These indicators are initiation of breast-feeding within one hour of birth, exclusive breast-feeding for 6 months, continued breast-feeding for 2 years, initiation of complementary feeds after 6 months, minimum meal frequency, minimum meal diversity, minimum acceptable diet and consumption of iron rich foods. These questions were included in the questionnaire. For IYCF indicators, a scoring system was established. A score of 7-8 was considered as excellent, 4-6 as good and <4 as poor.

Ethical Considerations

Institutional Research Committee, Symbiosis School of Biological Science in September 2018 and Institutional Ethics Committee of Symbiosis International (Deemed University) in January 2019, approved the research proposal. Before commencement of data collection in the month of December, permission for collecting the data from Anganwadi centres was granted by the supervisor and those who voluntarily agreed to participate.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Majority (62.4%) of mothers were in the age group of 21-29 years. Half of the mothers (51.1%) had pre-pregnancy age of < 21 years with 46.1% of them being in the age group of 21-29 years. Maximum (29.8%) children participating in the study belonged to the age group of 12-18 months followed by 28.4% in 0-6 months and 18.4% from age group of 19-24 months. It was seen that 53.6% were male children and the remaining 46.4 % were female. Parity i.e number of children borne by the mother was two at its maximum (45.4%) and three or more than three at minimum (19.1%). (Table 1)

Table 1: Maternal and child socio-demographic data

| Parameter | Categories | Frequency

(n) |

Percentage

(%) |

|

Age of Mother |

≤21 | 37 | 26.2 |

| 21-29 | 88 | 62.4 | |

| ≥30 | 16 | 11.3 | |

|

Pre-pregnancy age (years) |

≤21 | 72 | 51.1 |

| 21-29 | 65 | 46.1 | |

| ≥30 | 4 | 2.8 | |

|

Age (years) |

0-6months | 40 | 28.4 |

| 6-12 months | 33 | 23.4 | |

| 12-18months | 42 | 29.8 | |

| 19-24months | 26 | 18.4 | |

| Gender | Male | 76 | 53.9 |

| Female | 65 | 46.1 | |

|

Parity |

1 | 50 | 35.5 |

| 2 | 64 | 45.4 | |

| ≥3 | 27 | 19.1 |

Knowledge of Respondents about IYCF Practices

Majority (90.1%) of participants realised that breast milk was the first feed that should be consumed by the child after birth. 87.9% of the women knew the meaning of breast-feeding. 87.9% women knew that exclusive breast-feeding means that an infant should receive only breast milk up to 6 months of life. 90.1% of participants realised that the children should be initiated with complementary feeding after 6 months. When asked the reason for exclusively breast-feeding their child for the first 6 months, 53.2% reported that it provides all the nutrients a baby needs for growth during the first six months while 28.4% women did not know the reasoning behind this practice. The frequency with which a child should be fed was perceived as ‘on demand’ by 57.4% women and 29.4% thought the infant should be fed after every 2 hours. 48.9% women reported that the child becomes healthy as a benefit behind exclusive breast-feeding while 31.9% mothers did not mention the reason. 78.7% mothers did not know the benefits of exclusive breast-feeding to the health of the mother. When asked about remedies for increasing breast milk, 70.9% mothers reported that the milk is improved if a mother consumes a nutritionally diverse diet. 40.4% mothers did not mention the reason for initiating complementary feeds after 6 months. (Table 2)

Table 2: Knowledge of mother towards IYCF practices

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Feed after birth | ||

| Breast milk | 127 | 90.1 |

| Other | 13 | 9.2 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 0.7 |

| Exclusive breast-feeding means | ||

| Infants gets only breastmilk and no other liquids or foods

|

124 | 87.9 |

| Other | 1 | 0.7 |

| Don’t know | 16 | 11.3 |

| Knowledge of exclusive breast-feeding | ||

| Yes | 124 | 87.9 |

| No | 17 | 12.1 |

| Period of breast feeding | ||

| From birth to 6 months | 129 | 91.5 |

| Other | 3 | 2.1 |

| Don’t know | 9 | 6.4 |

| Initiation of complementary feeds | ||

| At 6 months | 127 | 90.1 |

| Other | 8 | 5.7 |

| Don’t know | 6 | 4.3 |

| Reason for exclusive breast-feeding | ||

| Provides all the nutrients and liquids a baby needs in its first six months

|

75 | 53.2 |

| Baby cannot digest other foods | 6 | 4.3 |

| Other | 13 | 9.2 |

| Don’t know | 40 | 28.4 |

| Decreased appetite | 7 | 5.0 |

| Number of times breast-feeding | ||

| On demand | 81 | 57.4 |

| Other | 10 | 7.1 |

| Don’t know | 8 | 5.7 |

| After every 2 hours | 42 | 29.4 |

| Benefits of exclusive breast-feeding to child | ||

| Health and development | 69 | 48.9 |

| Protection from diarrhoea and other infections | 12 | 8.5 |

| Protection against obesity and chronic diseases in adulthood | – | – |

| Other | 15 | 10.6 |

| Don’t know | 45 | 31.9 |

| Benefits of exclusive breast-feeding to mother | ||

| Delays fertility | 2 | 1.4 |

| Helps lose the weight gained during pregnancy | 6 | 4.3 |

| Lowers risk of cancer (breast and ovarian) | 1 | 0.7 |

| Lowers risk of losing blood after giving birth | 3 | 2.1 |

| Improves the relationship between the mother and baby | 2 | 1.4 |

| Other | 16 | 11.3 |

| Don’t know | 111 | 78.7 |

| Remedies for low breast milk | ||

| Manually expressing breastmilk | 8 | 5.7 |

| Having diversified nutritious diet | 100 | 70.9 |

| Drink enough liquids during the day | 5 | 3.5 |

| Other | 16 | 11.3 |

| Don’t know | 11 | 7.8 |

| Medicines | 1 | 0.7 |

| Reasons for initiating complementary feeds | ||

| Cannot supply all the nutrients needed for growth after 6 months of age | 30 | 21.3 |

| Other | 9 | 6.4 |

| Don’t know | 57 | 40.4 |

Attitude of Respondents towards IYCF Practices

The majority of participants reported that breastfeeding is good for the health of child, but a few (5%) were ambivalent . Approximately 80% reported that breast-feeding their baby is not difficult. However, 17% felt that it is difficult. Majority of mothers (90%) had a positive attitude i.e they agreed to breast-feed their child on demand but a huge portion of them (24.8%) thought of it to be less positive. Despite positive reports of breastfeeding shared by the participants, only 5.7% of the mothers felt confident when they actually breastfed their child and a majority of them did not have the clarity on the same. Interestingly, even though the majority of the mothers indicated that breastfeeding was healthy for their infant, 92% of the cohort reported being unsure of procedures related to expressing and storing breastmilk, with only 6% indicating a level of confidence (Table 3)

Table 3: Attitude of mother towards IYCF practices

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Breast feeding is good | ||

| Very good | 133 | 94.3 |

| Not sure | 7 | 5.0 |

| Not good | 1 | 0.7 |

| Breast feeding is difficult | ||

| Very difficult | 24 | 17.0 |

| Somewhat difficult | 5 | 3.5 |

| Not difficult | 112 | 79.4 |

| Breast feeding on demand is good | ||

| Very good | 90 | 63.8 |

| Not sure | 16 | 11.3 |

| Not good | 35 | 24.8 |

| Ability to breast feed | ||

| Able to breastfeed | 8 | 5.7 |

| Not sure | 122 | 86.5 |

| Unable to breastfeed | 11 | 7.8 |

| Ability towards expressing and storing breast milk | ||

| Able to express and store breastmilk | 6 | 4.3 |

| Not sure | 43 | 30.5 |

| Unable to express and store breastmilk | 92 | 65.2 |

IYCF Practices

A total of 79.4% children were breast-fed within an hour of their birth and 20.6% were not. 87.2% of children were exclusively breast-fed for the first six months of life and 41.1% children were continually breastfed for 2 years. 92.2% children started with complementary feeds after 6 months. 69.1% children had minimally diverse meals which included 4 or more than 4 food groups every day. 34.8% c 6-8 months infants were breastfed at least 2 times/day, 40.4% children of age 9-23 were breastfed at least 3 times/day, 7.8% children who were not breastfed and were fed solid food at least 4 times/day, 17% children were fed fewer number of times than those mentioned above. 60.3% children had minimal acceptable diet and 39.7% did not. Minimal acceptable diet was calculated by the researcher based on minimum meal frequency and minimum diet diversity of the participant. If a child does not fulfil either of those criteria, he/she was not considered to have a minimal acceptable diet. Nutritional analysis revealed that 36.2% children consumed iron-rich foods, 45.4% did not and 18.4% mothers were not sure about the same. (Table 4)

Table 4: IYCF Practices

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Breast feeding within one hour | ||

| Yes | 112 | 79.4 |

| No | 29 | 20.6 |

| Exclusive breast feeding for first 6 months | ||

| Yes | 123 | 87.2 |

| No | 18 | 12.8 |

| Continued breast feeding for 2 years | ||

| Yes | 58 | 41.1 |

| No | 66 | 46.8 |

| Don’t know | 17 | 12.1 |

| Initiation of complementary feeds after 6 months | ||

| Yes | 130 | 92.2 |

| No | 9 | 6.4 |

| Don’t know | 2 | 1.4 |

| Minimum diet diversity (≥4) | ||

| Yes | 96 | 69.1 |

| No | 45 | 31.9 |

| Minimum meal frequency of complementary foods | ||

| 2 times for breastfed infants 6–8 months | 49 | 34.8 |

| 3 times for breastfed children 9–23 months | 57 | 40.4 |

| 4 times for non-breastfed children 6–23 months | 11 | 7.8 |

| No | 24 | 17.0 |

| Minimum acceptable diet | ||

| Yes | 85 | 60.3 |

| No | 56 | 39.7 |

| Consumption of iron-rich foods | ||

| Yes | 51 | 36.2 |

| No | 64 | 45.4 |

| Don’t know | 26 | 18.4 |

|

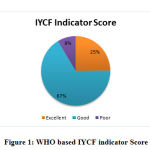

Figure 1: WHO based IYCF indicator Score |

There are eight core indicators set prescribed by WHO and UNICEF for assessing the correctness of feeding infant and young children. The above figure demonstrates the scores of mothers of children in the age group of 0-2 years. A quarter of women had an “excellent” IYCF indicator score meaning a score of more than 7 out of 8, 67% have “good” scores, meaning a score of more than 4 and mere 8% show “poor” scores with a score of less than 4. (Figure 1)

Discussion

Overall it was observed that mothers had good knowledge about IYCF practices. It was reported in one study that 59.1% mothers knew about duration of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) and 50.2% knew the benefits of EBF to the child. In the same study, 62.1% mothers knew about duration of breast-feeding, 52.8% knew the frequency with which breastmilk should be given, 76.4% knew the duration, and 62.3% knew the initiation time of complementary feeds18. A similar study also revealed good knowledge perceived by the mothers about IYCF practices with a less favourable attitude 19.

Mother’s attitude about IYCF practices was less evidenced than the general knowledge base. In a similar study by Rajput R., 2017, 82.2% mothers had a positive attitude about EBF20. On the contrary, other study by Jain S, 2017 did not find a desirable attitude of mothers towards IYCF practices even though the mothers perceived good knowledge. It was reported that imparting knowledge without changing the attitude of mothers towards IYCF practices will not give rise to good practices 19. Similar finding were supported in the current study as well.

Poor practices on the other hand, can be one of the reasons for poor growth of children. In a study conducted in Solapur city of Maharashtra, only 41.25% mothers exclusively breast-fed their child and 58.75% fed complementary foods to their children before 6 months of age21. One such study by Krishnendu.M, 2017 in Kerala reported that 84.1% mothers exclusively breast-fed their child22. It was reported that mothers practice in feeding the child was poor despite of mothers having good knowledge. 19–21. Hence, it reinforces the fact that only imparting knowledge is not enough, but imparting it through hands on training and practical exposure is the key to improve the feeding practices.

IYCF indicators followed by the children in the present study were good. It has been reported that 76.3% mothers breastfed their child for first 6 months, 78% children were introduced to complementary feeds after 6 months and had excellent IYCF score whilst the present study had good scores on the IYCF indicators23. In a study by Abdi Guled et al., 2017, 47% mothers initiated breast-feeding the child within one hour of birth which is lower than the current study. In addition, 92% of the mothers recognised the recommended duration for early breast feeding, 96.9% knew about the duration for exclusive breastfeeding, although only 25% knew about the time to start complementary feeds20. In a study conducted in Mumbai, it was reported that 46% infants were breast-fed within one hour of birth, 63% were breast-fed exclusively, 74% were breast-fed for 12 months and only 41% were started with complementary feeds at age of 6months, a mere 13% fulfilled the criteria for minimum diet diversity, 43% for minimum meal frequency and 5% had minimum acceptable diet i.e food consumed apart from breastmilk 24. A similar study by Tegegne M, 2017 reported fulfilment of minimum meal frequency and minimum meal diversity by 28.5% and 68.4% respectively25. This is true for minimum meal frequency i.e consumption of atleast 2-3 meals a day reported in the current study and not for diet diversity i.e the no. of food groups consumed per day, as it is comparatively higher. Iron consumption based on the nutrient analysis was also found to be higher in other studies as compared to the present study23.

There have been studies indicating how knowledge may not always translate into good attitude and vice-versa. Guled et al, 2017 did not find a significant association between knowledge and favourable attitude20. Knowledge gaps were found to be common in Hyderabad too26. Jain. S, 2017 did not find a desirable attitude of mothers towards IYCF practices even though the mothers perceived good knowledge. 19. Although, good knowledge should give rise to correct practices and the fact that such is not the case here highlights the importance of an intervention 20,27. Further changes in the practices of mothers can be accomplished by imparting practical knowledge such as hands on training about breastfeeding, storing of breastmilk, preparation of complementary feeds under hygienic conditions and overall the importance of carrying out good practices and its impact on child growth and survival.

The significant difference between knowledge and actual practise may be underlying factor for child malnutrition in India. Though a strong knowledge base is important for supporting the mother in feeding practices to optimize health of the child, our study indicates that practical application, may further support IYCF practices.

Strengths and Limitations

The questionnaire utilised for this study is based on the WHO IYCF Indicators parameters as well as pilot study was also conducted for its implementation in an Indian scenario. This study was the first to be conducted in rural areas of Nanded. However the limitation of the study is that it was conducted among lactating mothers that opted for post-natal services and hence, the findings of this study may not be representative of the situation of infant and young child feeding practices for the community at large.

Conclusions

Overall mothers had good knowledge and a fair attitude about IYCF practices. However, owing to a higher percent prevalence, specific nutrition guidelines related to food and nutrient intakes such as iron and nutrient dense meals, counselling on IYCF practices should be planned for the mothers attending post natal checkups. Behaviour change communications intervention strategies, which would support IYCF practices, should be introduced in mothers to bridge the gap between knowledge and practices.

Conflict of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the mothers who participated in this study and the Anganwadi supervisor and Anganwadi workers for smooth conduct of the study.

References

- Puri S. Transition in Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices in India. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2017;13(5). doi:10.2174/1573399812666160819152527

- TIWARI S, KETAN BHARADVA, BALRAJ YADAV, et al. Infant and Young Child Feeding Guidelines, 2016. Indian Pediatrics. 2016;15;53.

- Weltgesundheitsorganisation. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: WHO. 2003:30p.

- Black R. et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. (Maternal and Child Undernutrition Series. 2008.

- Bentley ME, Johnson SL, Wasser H, et al. Formative research methods for designing culturally appropriate, integrated child nutrition and development interventions: an overview: Formative methods for integrated interventions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2014;1308(1):54-67. doi:10.1111/nyas.12290

- Black MM, Perez-Escamilla R, Fernandez Rao S. Integrating Nutrition and Child Development Interventions: Scientific Basis, Evidence of Impact, and Implementation Considerations. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal. 2015;6(6):852-859. doi:10.3945/an.115.010348

- Childhood Development in Developing Countries Series. 2007.

- Debes AK, Kohli A, Walker N, Edmond K, Mullany LC. Time to initiation of breastfeeding and neonatal mortality and morbidity: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(Suppl 3):S19. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S19

- Johnson TJ, Patel AL, Bigger HR, Engstrom JL, Meier PP. Economic Benefits and Costs of Human Milk Feedings: A Strategy to Reduce the Risk of Prematurity-Related Morbidities in Very-Low-Birth-Weight Infants. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal. 2014;5(2):207-212. doi:10.3945/an.113.004788

- Khan J, Vesel L, Bahl R, Martines JC. Timing of Breastfeeding Initiation and Exclusivity of Breastfeeding During the First Month of Life: Effects on Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity—A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015;19(3):468-479. doi:10.1007/s10995-014-1526-8

- Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica. 2015;104:3-13. doi:10.1111/apa.13147

- Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475-490. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7

- Chaudhary N, Raut A, Singh A. Faulty feeding practices in children less than 2 years of age and their association with nutritional status: A study from a rural medical college in Central India. International Journal of Advanced Medical and Health Research. 2016;3(2):78. doi:10.4103/2349-4220.195943

- Norhan Zeki Shaker, Dr. Sawsan I.I. AL-Azzawi, Dr. Kareema Ahmad Hussein. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) of Mothers toward Infant and Young Child Feeding in Primary Health Care (PHC) Centers, Erbil City. ). J Kufa J Nurs Sci. 2014;(3;2(2).

- Patel A, Pusdekar Y, Badhoniya N, Borkar J, Agho KE, Dibley MJ. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in young children in India: secondary analysis of National Family Health Survey 2005-2006: Complementary feeding practices in India. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2012;8:28-44. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00385.x

- Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475-490. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7

- World Health Organization (WHO). Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Conclusions of a Consensus Meeting Held 6-8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. Washington, D.C.: World Health Organization (WHO); 2008.

- Choudhary A, Bankwar V, Choudhary A. Knowledge regarding breastfeeding and factors associated with its practice among postnatal mothers in central India. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health. 2015;4(7):973. doi:10.5455/ijmsph.2015.10022015201

- Jain S, Thapar RK, Gupta RK. Complete coverage and covering completely: Breast feeding and complementary feeding: Knowledge, attitude, and practices of mothers. Medical Journal Armed Forces India. 2018;74(1):28-32. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2017.03.003

- Abdi Guled et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of mothers/caregivers on infant and young child feeding in Shabelle zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. 2017;6(2):42-54.

- Rajput RR, Haralkar SJ, Mangulikar SK. A study of knowledge and practice of breast feeding in urban slum area under urban health centre in Solapur city, Western Maharashtra. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health. 2017;4(12):4692. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20175352

- Krishnendu M, Devaki G. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Breasfeeding among Lactating Mothers in Rural Areas of Thrissur District of Kerala, India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal. 2017;10(02):683-690. doi:10.13005/bpj/1156

- Khor G, Tan S, Tan K, Chan P, Amarra M. Compliance with WHO IYCF Indicators and Dietary Intake Adequacy in a Sample of Malaysian Infants Aged 6–23 Months. Nutrients. 2016;8(12):778. doi:10.3390/nu8120778

- Bentley A, Das S, Alcock G, Shah More N, Pantvaidya S, Osrin D. Malnutrition and infant and young child feeding in informal settlements in Mumbai, India: findings from a census. Food Science & Nutrition. 2015;3(3):257-271. doi:10.1002/fsn3.214

- Tegegne M, Sileshi S, Benti T, Teshome M, Woldie H. Factors associated with minimal meal frequency and dietary diversity practices among infants and young children in the predominantly agrarian society of Bale zone, Southeast Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. Archives of Public Health. 2017;75(1). doi:10.1186/s13690-017-0216-6

- Mane SS, Chundi PR. Infant and young child feeding practices among mothers in Hyderabad, Telangana. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health. 2017;4(10):3808. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20174255

- Nankumbi J, Muliira JK, Kabahenda MK. Feeding Practices and Nutrition Outcomes in Children: Examining the Practices of Caregivers Living in a Rural Setting. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition. 2012;4(6):373-380. doi:10.1177/1941406412454166

Abbreviations

KAP: Knowledge attitude practices, EBF: exclusive breastfeeding, IYCF: Infant and Young Child feeding Practices, WHO: World Health organisation, NFHS: National Family Health Survey