Aroonika. S. Bedre1, Radhika Arjunkumar2 and Muralidharan N. P3

1Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University Chennai, India.

2Department of Periodontics, Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University Chennai, India.

3Department of Microbiology Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University Chennai, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: radhikaarjunkumar@gmail.com

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1424

Abstract

This study focuses on evaluating the concentration dependent antimicrobial efficacy of herbal dentifrice (tooth paste) in comparison with a conventional non dentifrice. One non -herbal dentifrice and three herbal dentifrices were selected for this study. Saliva samples were collected from 10 healthy individuals. All toothpaste samples were diluted in saline in 25%, 50% and 100% concentrations. Their antimicrobial activity was determined by modified agar well diffusion method. Five wells were cut at equidistance in each of the nutrient agar plates. The plates were seeded with saliva sample. Dentifrice dilutions were introduced into the wells. The plates were incubated overnight and the diameter of zones of inhibition was measured. The antimicrobial efficacy was similar in herbal and non-herbal dentifrices and also in their different concentrations. We can advocate herbal dentifrices, as there is a sudden surge in the concern over using chemical and non-herbal products. Thus, comparable properties with standard pastes makes herbal pastes a viable option for plaque control.

Keywords

Antimicrobial Efficacy; Dentifrices; Herbal Toothpaste; Non-Herbal Toothpaste; Salivary Micro Flora

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Bedre A. S, Arjunkumar R, Muralidharan N. P. Evaluation of Concentration Dependent Antimicrobial Efficacy of Herbal and Non Herbal Dentifrices Against Salivary Microflora – An In Vitro Study. Biomed Pharmacol J 2018;11(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Bedre A. S, Arjunkumar R, Muralidharan N. P. Evaluation of Concentration Dependent Antimicrobial Efficacy of Herbal and Non Herbal Dentifrices Against Salivary Microflora – An In Vitro Study. Biomed Pharmacol J 2018;11(2). Available from: http://biomedpharmajournal.org/?p=20437 |

Introduction

Dental plaque can be defined as the soft deposits that form the biofilm adhering to the tooth surface or other hard surfaces in the oral cavity, including removable and fixed restorations.1 Microorganisms present in dental plaque cause dental caries and periodontal diseases.2 Dental caries is a localized, transmissible infectious process that ends up in the destruction of hard dental tissue. It results from accumulation of plaque on the surface of the teeth and biochemical activities of complex micro-communities. Streptococcus mutans is one of the main opportunistic pathogens of dental caries,3 which plays a central role in fermenting carbohydrates resulting in acid production, and leading to the demineralization of the tooth enamel. In addition, other microflora like Escherichia coli and Candida are also associated with active caries lesions. Candida albicans is the most common yeast isolated from the oral cavity. It is by far the fungal species most commonly isolated from infected root canals, showing resistance to intracanal medication.4 Poor oral hygiene is one of the reasons for accumulation of these microbes and their harmful activities. Periodontal diseases are bacterial infections that affect the supporting structure of the teeth (gingival, cementum, periodontal membrane and alveolar bone). The hydrolytic enzymes, endotoxins, and toxic bacterial metabolites are involved in this disease. Gingivitis, an inflammatory condition of gum, is the most common form of periodontal disease. Serious forms of periodontal disease that affect the periodontal membrane and alveolar bone may result in tooth loss. Streptococci, Spirochetes and Bacteroides are found to be the possible pathogens responsible for the disease.5

Biofilm formation is a natural process in the oral environment, but needs to be controlled through regular brushing in order to prevent the development of caries and periodontal diseases.6 Tooth brushing with toothpaste is the most widely practiced form of oral hygiene in most countries.7 Nevertheless, in many individuals, the customary oral hygiene method of tooth brushing is, by itself, usually insufficient over a long period to provide a level of plaque control consistent with oral health.8 Hence, the addition of antimicrobial agents to toothpaste has been suggested as one possible method to improve the efficacy of mechanical tooth-cleaning procedures, aiding the control of dental plaque and preventing dental caries and periodontal diseases.11,12 When these substances are added to oral products, they kill microorganisms by disrupting their cell walls and inhibiting their enzymatic activity. They prevent bacterial aggregation, slow multiplication and release endotoxins.12-14 Several clinical studies have demonstrated the inhibitory effects of antimicrobial dentifrices, commonly known as tooth- pastes, on oral bacteria and gingiva.8,10,15 Also, the antimicrobial agents in dentifrices can significantly reduce contamination of toothbrushes.16,17

Fitzgerald, Jordan, and Achard in 1964,18 demonstrated that dental caries would not occur in the absence of microorganisms. Complete removal of microorganisms from the oral cavity is impossible, but reduction in microbial count may reduce the cariogenic effect. Oral cavity is an ecological niche, which contains 500–1000 different types of bacteria along with fungi, protozoa, and occasionally viruses. Oral microflora increases due to frequent intake of sucrose and carbohydrate and poor oral hygiene and decreases due to various preventive measures such as topical fluoride application, pit and fissure sealants, etc., the mechanical measures used in our daily routine, such as tooth brushing, dental flossing, etc., if complimented with a dentifrice having antimicrobial efficacy, can reduce the microbial count of the oral cavity on a daily basis and, thus, reduce the prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease.

Routinely used synthetic dentifrices contain fluoride and triclosan, which are known to produce harmful side effects such as mucosal ulceration, circum-oral dermatitis, dental fluorosis, etc. on prolonged use.19,20 Hence, despite the efficacy of many synthetic toothpaste formulations with antibacterial properties,21,22 there is an increasing societal desire to rely on naturally occurring compounds for health care, which has also found its way into dentistry.23 Consumers who gravitate towards using herbal products often view these products as being much safer. Their efficacy can be attributed to various properties such as anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, astringent action, anti-diabetic, anti-fungal, analgesic and antiseptic properties.24 herbs have been used in India and south Asia for thousands of years to clean and fight bacterial and fungal infections.25 Herbal medicine has made significant contribution to modern medical practice as well.26 The antimicrobial activity of the herbs is due to the presence of secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, flavonoids, polyphenols, and lectins.27 This study focuses on evaluating the concentration dependent antimicrobial efficacy of 3 herbal dentifrices in comparison with a conventional non herbal dentifrice.

Materials and Methods

Four toothpastes namely one non herbal toothpaste: Pepsodent Germicheck and three herbal tooth pastes: Lever – Ayush Anti Cavity Clove Oil, Dabur Red and Himalaya Sparkling White were selected for assessment of their in vitro antimicrobial activity. The products were collected from local market, Chennai. Approval was obtained from the Institution’s Ethical Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Selection of Patients

Inclusion Criteria

10 participants in the age group of 19–21 years with good general health following routine oral hygiene procedures and agreement to comply with the study visits were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Participants suffering from systemic diseases, currently using antibiotics, undergoing orthodontic treatment, using additional oral

Hygiene aids other than toothbrush & toothpaste, having adverse habits like smoking, alcohol consumption were excluded from the

Study.

Method of Saliva Collection and Storage

The subjects were told to rinse with water; saliva was allowed to accumulate in the floor of the mouth for approximately two minutes and by asking the subject to spit in uricol container. By following the above mention method, 10 samples were collected in the early morning time. The samples were transported immediately to the laboratory.

Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of Toothpastes

All toothpaste samples were diluted in saline and prepared series dilution. The concentrations considered – 25%, 50% and 100%.

Antimicrobial Assay

The antimicrobial activity of different concentrations of the dentifrices was determined by modified agar well diffusion method. In this method, nutrient agar plates were seeded with 0.5 ml collected saliva sample for 24h. The plates were allowed to dry for 1 h. A sterile 8 mm cork borer was used to cut one central and two wells at equidistance in each of the plates. Dentifrice dilutions at different concentrations were introduced into each of the three wells. The plates were incubated at 37ºc for 24 h. The antimicrobial activity was evaluated by measuring the zone of inhibition around the wells.

Results

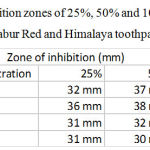

From Table 1 and Figure 1, non -herbal tooth paste (Pepsodent Germicheck) showed zones of inhibition of 32 mm, 37 mm, and 37 mm in 25%, 50% and 100% concentrations respectively.

Herbal toothpaste a (Ayush clove oil) showed zones of inhibition of 36 mm, 38 mm, and 32 mm in 25%, 50% and 100% concentrations respectively.

Herbal toothpaste b (Dabur Red) showed zones of inhibition of 31 mm, 32 mm, and 35 mm in 25%, 50% and 100% concentrations respectively.

Herbal toothpaste c (Himalaya sparkling white) showed zones of inhibition of 31 mm, 30 mm, and 33 mm in 25%, 50% and 100% concentrations respectively.

Comparing the zones of inhibition across the varying concentrations of the different dentifrices it was observed that the antimicrobial efficacy was similar in herbal and non-herbal toothpastes and also in their different concentrations.

Table 1: Shows inhibition zones of 25%, 50% and 100% concentrations of Pepsodent, Ayush, Dabur Red and Himalaya toothpastes.

|

Table 1: Shows inhibition zones of 25%, 50% and 100% concentrations of Pepsodent, Ayush, Dabur Red and Himalaya toothpastes.

|

|

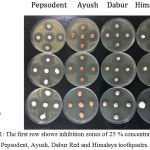

Figure 1: The first row shows inhibition zones of 25 % concentrations of Pepsodent, Ayush, Dabur Red and Himalaya toothpastes.

|

The second row shows inhibition zones of 50 % concentration of the toothpastes. And the third row shows inhibition zones of 100 % concentration of the tooth pastes.

Discussion

Microorganisms play a vital role in causation of dental caries. Various studies [18] have provided evidence of bacterial specificity in caries aetiology. Complete removal of microorganisms from the oral cavity is impossible, but their count can be reduced so that it becomes less cariogenic with the help of various preventive measures, for example, probiotics, antibiotics, fluorides, and oral hygiene aids. Various oral hygiene measures are available, such as tooth brushing, dental flossing, mouthwashes, dentifrices, etc., among which tooth brushing with dentifrice is the most commonly used. These mechanical measures are feasible, cost-effective, and can easily be used by children. Dentifrices are therapeutic mechanical aids which are available as tooth powder or toothpaste and aid in removal of plaque. Their antimicrobial effect has been proven in various studies.28

In our study, four toothpastes namely one non herbal toothpaste (pepsodent germicheck) and three herbal tooth pastes (ayush clove oil, dabur red and himalaya sparling white) were selected for assessment of their in vitro antimicrobial activity.

Tooth paste – a (pepsodent germicheck magnets) contains calcium carbonate, water, sorbitol, hydrated silica, sodium lauryl sulphate, flavour, cellulose gum, sodium silicate, benzyl alcohol, sodium saccharin, potassium nitrate, triclosan, sodium monofluoro phosphate and titanium dioxide. Tooth paste- b (lever ayush anti cavity clove oil) contains clove oil and dasanakathi choornam. Tooth paste -c (dabur red) contains clove oil, pudina satva,tomar beej (zanthoxylum alatum) and sunthi (ginger). Tooth paste- d (himalaya sparkling white) contains miswak, almond, pineapple, papaya, cinnamon and clove.

In fluoridated dentifrice, fluoride is mostly available in the form of sodium fluoride or sodium monofluorophosphate.29 Antimicrobial activity of fluoridated toothpastes occurs by interfering with the glucose transport, carbohydrate storage, extracellular polysaccharide formation and acid formation by oral streptococci.15

Triclosan (2,4,4’-trichloro-2’hydroxydiphenylether) is a phenolic agent with broad-spectrum antibacterial activity that disrupts bacterial cytoplasmic membranes by blocking fatty acid biosynthesis i.e., the enzyme enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (enr).2,30,31,32

Although the commonly used and recommend toothpastes by WHO, ADA, FDI is the fluoride and triclosan containing, some of the constituents of these toothpastes have undesirable side effects like staining, abrasions and taste alterations.13,25 Moreover, these pastes are not recommended in high fluoridated belt and also in children under 3 years of age as they could cause dental fluorosis, skeletal fluorosis and destruction of epithelial layer of intestine.33 Thus, the quest for a dentifrice which has less abrasive effect, less chemical agents, and more antimicrobial property made the researchers focus on age-old medicinal alternative “herbs.”29

The antimicrobial activity of plant extracts is due to the presence of secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolics, polyphenols, quinines, flavones, flavonols, tannins, terpenoids, lectins, polypeptides, proanthocynidins, tannins, and quercetin.34 plant extracts provide protection by immune stimulation and do not have any known side effects.35 clove oil has biological activities, such as antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal and antioxidant properties, and is used traditionally as a savoring agent and antimicrobial material in food .36,37,38 In addition, clove oil is used as an antiseptic in oral infections.39,40 This essential oil has been reported to inhibit the growth of molds, yeasts and bacteria.41 The high levels of eugenol contained in clove essential oil are responsible for its strong biological and antimicrobial activities. It is well known that both eugenol and clove essential oil phenolic compounds can denature proteins and react with cell membrane phospholipids changing their permeability and inhibiting a great number of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria as well as different types of yeast.42,43 Meswak herb is a rare, potent, priceless wonder herb that delivers incredible oral care benefits. It is scientifically proven to reduce tartar and plaque, fights germs and bacteria to keep the gum healthy, helps prevent tooth decay, eliminates bad breath, and ensures strong teeth. In sa. Persica (meswak), a natural component benzylisothiocyanate (bit) is present that acts as an inhibitor of bacterial growth and their acidic products. Also, the antibiotic effects found in meswak may prevent the attachment of bacteria.44 the antibacterial effects of cinnamon is due to its active constituents such as cinnamaldehyde and eugenol.45 the antibacterial activity and inhibition activity of ginger extracts could be attributed to zingiberene. Other components include β- sesquiphellandrene, bisabolene and farnesene, which are sesquiterpenoids, and trace monoterpenoid fraction, (β sesquiphellandrene, cineol and citral).46 The principle active constituents of peppermint are the essential oils, which comprise about 1% of the herb. The oils are dominated by monoterpenes, mainly menthol, menthone and their derivatives (e.g., isomenthone, neomenthol, acetylmenthol, pulegone). These essential oils dilate blood vessels and inhibit bacteria. Especially menthol has a broad spectrum antibacterial activity.47The antibacterial activity of Carica papya may be attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds such as phenols, saponin, steriods, alkaloids and flavonoids .48

In our study, the antimicrobial efficacy was similar in herbal and non-herbal tooth pastes and also in their different concentrations. Based on another study by Mahesh R. K. et al, there is a trend to believe that the herbal toothpastes possess significant salivary glucose inhibitory activity and favor transient increase in salivary ph.49 The anti-plaque and anti-gingival effects of herbal toothpaste, which were comparable to those of conventional toothpastes.50,51,52,53,54 In a study by Vyas Y.K., Arodent, a herbal tooth paste possesses good antibacterial activity against both cariogenic bacteria S. mutans and L. acidophilus, and its antibacterial activity is comparable to the standard dentifrice Colgate.55 Another study by Neha Bhati et al states that the three test dentifrices (tooth brushing using non-herbal fluoridated dentifrice, A. Vera containing dentifrice, and meswak containing dentifrice) have equal antimicrobial efficacy.29 it can be inferred from the above results that the herbal dentifrice is as efficacious as the conventionally formulated dentifrice and could be used as an alternative for people interested in natural products.

Although the bacterial count had shown reduction in 15 days and remained the same over a period of 1 month (30 days), the prolonged effect on the bacterial count, as well as whether the reduced count is stabilized or the counts return back to baseline values need to be checked. Whether there is any bacterial resistance developing to these products also needs to be monitored carefully in further studies.29 Herbal products had less potency as an antimicrobial agent in a study, but the tannins, flavonoids and lectins present in it definitely strengthens the periodontium and gingival tissue.56 It can definitely be used in children upto 3 years of age to avoid fluoride toxicity as fluoride uptake upto 0.3-0.6ppm is sufficient for this age group which generally met through the dietary supplements and drinking water as specified by the AAPD guidelines 2013.57

Conclusion

We can advocate herbal dentifrices, as there is a sudden surge in the concern over using chemical and non-herbal products. Thus, comparable properties with standard dentifrices make herbal dentifrices a viable option for plaque control.

References

- Carranza. Clinical periodontology. 9th edi. Philadephia: w.b. saunders. 2002;97.

- Kachare et al. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of two commercially available dentifrices (fluoridated and herbal) against salivary microflora. Int j pharm pharm sci. 2004;6(6):72-74.

- Gamboa F, Estupinan M, Galindo A. Presence of streptococcus mutansin saliva and its relationship with dental caries: antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolates. Universitas scientiarum. 2004;9(2):23–7.

- Oztan M.d, Kiyan M, Gerceker D. Antimicrobial effect, in vitro, of gutta-percha points containing root canal medications against yeasts and enterococcus faecalis. Oral surg oral med oral pathol oral radiol endod. 2006;102(3):410–6.

CrossRef - Prasanth M et al. Antimicrobial efficacy of different toothpastes and mouthrinses: an in vitro study. Dent res j (isfahan). 2011;8(2):85–94.

- Davies R.M. Toothpaste in the control of plaque/gingivitis and periodontitis. Periodontology. 2008;2000(48):23–30.

CrossRef - Pannuti C.M, Mattos J.P, Ranoya P.N, Jesus A.M, Lotufo R.F, Romito G.A. Clinical effect of a herbal dentifrice on the control of plaque and gingivitis: a double-blind study. Pesqui odontol bras. 2003;17(4):314–8.

CrossRef - Menendez A, Li F, Michalek S.m, Kirk K, Makhija S.K, Childers N.K. Comparative analysis of the antibacterial effects of combined mouthrinses on streptococcus mutans. Oral microbiol immunol. 2005;20(1):31–4.

CrossRef - Moran J, Addy M, Newcombe R. The antibacterial effect of toothpastes on the salivary flora. J clin periodontol. 1988;15(3):193–9.

CrossRef - Fine D.H, Furgang D, Markowitz K, Sreenivasan P.K, Klimpel K, De Vizio W. The antimicrobial effect of a triclosan/copolymer dentifrice on oral microorganisms in vivo. J am dent assoc. 2006;137(10):1406–13.

CrossRef - White D.J, Kozak K.M, Gibb R, Dunavent J, Klukowska M, Sagel P.a. A 24-hour dental plaque prevention study with a stannous fluoride dentifrice containing hexametaphosphate. J contemp dent pract. 2006;7(3):1– 11.

CrossRef - Ozaki F, Pannuti C.M, Imbronito A.V, Pessotti W, Saraiva L, De Freitas N.M, et al. Efficacy of a herbal toothpaste on patients with established gingivitis a randomized controlled trial. Braz oral res. 2006;20(2):172–7.

CrossRef - Bou-Chacra N.A, Gobi S.S, Ohara M.T, Pinto T.J.A. Antimicrobial activity of four different dental gel formulas on cariogenic bacteria evaluated using the linear regression method. Revista brasileira de ciencias farmaceuticas. 2005;41(3):323–31.

CrossRef - Herrera D, Roldan S, Santacruz I, Santos S, Masdevall M, Sanz M. Differences in antimicrobial activity of four commercial 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthrinse formulations: an in vitro contact test and salivary bacterial counts study. J clin periodontol. 2003;30(4):307–14.

CrossRef - Jabbarifar S.E, Tabibian S.A, Poursina F. Effect of fluoride mouth rinse and toothpaste on number of streptococcal colony forming units of dental plaque. Research in medical sciences, isfahan university of medical sciences journal. 2005;10(6):363–7.

- Quirynen M, De Soete M, Pauwels M, Gizani S, Van Meerbeek B, Van Steenberghe D. Can toothpaste or a toothbrush with antibacterial tufts prevent toothbrush contamination?. J periodontol. 2003;74(3):312–22.

CrossRef - Efstratiou M, Papaioannou W, Nakou M, Ktenas E, Vrotsos Ia, Panis V. Contamination of a toothbrush with antibacterial properties by oral microorgan-isms. J dent. 2007;35(4):331–7.

CrossRef - Mcdonald R.E, Avery D.R, Dean J.A. 8th ed. Ch 10. Mosby; Dentistry for the child and adolescent. 2004;205.

- Davies R., Scully C., Preston A.J. dentifrices–an update. Med oral patol oral cir bucal. 2010;1;15(6):976–982. [pubmed] CrossRef

- Goldstein B.H, Epstein J.B. Unconventional Dentistry: part iv. Unconventional dental practices and products. J can dent assoc. 2000;66(10):564–568.

- Gunsolley J.C. A meta-analysis of six-month studies of antiplaque and antigingivitis agents. Journal of the american dental association (1939). 2006;137(12):1649-57.

CrossRef - Bratthall D, Hänsel-Petersson G, Sundberg H. Reasons for the caries decline: what do the experts believe? European. journal of oral sciences 1996;104(4 (pt 2)):416-22; discussion 23.

CrossRef - Lee S.S, Zhang W, Li Y. The antimicrobial potential of 14 natural herbal dentifrices: results of an in vitro diffusion method study. Journal of the american dental association (1939). 2004;135(8):1133-41.

CrossRef - Mahesh R. Khairnar, efficacy of herbal toothpastes on salivary ph and salivary glucose – a preliminary study. J ayurveda integr med. 2017;8(1): 3–6.

CrossRef - De Oliveira S.M, Torres T.C, Pereira S.L, Mota O.M, Carlos M.X. Effect of a dentifrice containing aloe vera on plaque and gingivitis control. A double-blind clinical study in humans. J appl oral sci. 2008;16:293–6.

CrossRef - Almas K, Dahlan A, Mahmoud A. Propolis as a natural remedy: an update. Saudi dental society. 2001;13(1):45-9.

- Fatima S, Farooqi A.h, Kumar R, Khanuja S.P. Antibacterial activity possessed by medicinal plants used in tooth powder. Arom pl sci 2000;22:187-9.

- Leyster C.W. An investigation of the levels of antimicrobial efficacy in commercial dentifrices on streptococcus mutans and lactobacillus. St martin’s univ bio j. 2006;1:155–66.

- Neha Bhati, Shipra Jaidka, and Rani Somani. Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of Aloe vera and Meswak containing dentifrices with fluoridated dentifrice: An in vivo study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5(5): 394–399.

CrossRef - Davies R. M, Ellwood R P, Davies G. M. The effectivenessof a toothpaste containing triclosan and polyvinyl-methyl ether maleic acid copolymer in improving plaque control and gingival health: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:1029-1033.

CrossRef - Kampf G, Kramer A. Epidemiologic background of hand hygiene and evaluation of themost important agents for scrubs and rubs. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:863-893.

CrossRef - Russell A D. Whither triclosan? .J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:693-695.

CrossRef - Susheela A.K. Dental fluorosis. In: A treatise on fluorosis. Fluorosis Research and Rural Development Foundation: Delhi. 2003;43-57.

- Cowan M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(56):45-82.

CrossRef - Fatima S, Farooqi A.H, Kumar R, Kumar T.R, Khanuja S.P. Antibacterial activity possessed by medicinal plants used in tooth powder. J Med Arom Pl Sci. 2000;22:187-9.

- Huang Y, Ho S.H, Lee H.C, Yap Y.L. Insecticidal properties of eugenol, isoeugenol and methyleugenol and their effects on nutrition of Sitophilus zeamais Motsch. J. Stored Prod. Research. 2002;38:403–412.

CrossRef - Lee K.G, Shibamoto T. Antioxidant property of aroma extract isolated from clove buds. Food Chem. 2001;74:443–448.

CrossRef - Nuñez L, D Aquino M, Chirife J. Antifungal properties of clove oil (Eugenia caryophylata) in sugar solution. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2001;32:123–126.

CrossRef - Meeker H.G, Linke H.A.B. The antibacterial action of eugenol, thyme oil, and related essential oils used in dentistry. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 1988;9:33–40. Shapiro S, Meier A, Guggenheim B. The antimicrobial activity of essential oils and essential oil components towards oral bacteria. Oral Microbiol. Immunol.1994;9:202–208.

CrossRef - Matan N, Rimkeeree H, Mawson A.J., Chompreeda P, Haruthaithanasan V, Parker M. Antimicrobial activity of cinnamon and clove oils under modified atmosphere conditions. J. Food Microbiol. 2006;107:180–185.

CrossRef - Chaib K, Hajlaoui H, Zmantar T, Kahla-Nakbi A.B, Rouabhia M, Mahdouani K, Bakhouf A. The chemical composition and biological activity of clove essential oil, Eugenia caryophyllata (Syzigium aromaticum L. Myrtaceae): a short review. Phythoter. Res. 2007;21:501–506.

CrossRef - Walsh S.E, Maillard J.-Y, Russell A.D, Catrenich C.E, Charbonneau D.L, Bartola R.G. Activity and mechanisms of action of selected biocidal agents on Gram-positive and – negative bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;94:240–247.

CrossRef - Ahmad H, Ahamed N. Therapeutic properties of Meswak chewing sticks: A review. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11(148):50–7.

- Seyed Fazel Nabavi, Arianna Di Lorenzo, and Seyed Mohammad Nabavi. Antibacterial Effects of Cinnamon: From Farm to Food, Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Industries. Nutrients. 2015;7(9):7729–7748.

CrossRef - Kamrul Islam, Asma Afroz Rowsni, M.D. Murad Khan and M.D. Shahidul Kabir* Antimicrobial activity of Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) extracts against food-borne pathogenic bacteria. International Journal of Science, Environmentand Technology. 2014;3(3):867 – 871.

- Bupesh C. Amutha S. Nandagopal A. Ganeshkumar P. Sureshkumar K. Saravana Murali.2007. Antibacterial activity of Mentha piperita L. (peppermint) from leaf extracts – a medicinal plant. Acta agriculturae Slovenica. 2007;1-89.

CrossRef - Murugan M. and Mohan V. R. Antibactrial of Maducusatropurpura. 2(3):277-280.

- Mahesh R. Khairnar Arun S. Dodamani and Manjiri A. Deshmukh. Efficacy of herbal toothpastes on salivary pH and salivary glucose – A preliminary study. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2017;8(1):3–6.

CrossRef - George J, Hegde S, Rajesh K.S, Kumar A. The efficacy of a herbal-based toothpaste in the control of plaque and gingivitis: A clinic-biochemical study. Indian J Dent Res. 2009;20:480–2.

CrossRef - Radafshar G, Mahboob F, Kazemnejad E. A study to assess the plaque inhibitory action of herbal-based toothpaste: A double blind controlled clinical trial. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4(11):82–6.

- Ozaki F, Pannuti C.M, Imbronito A.V, Pessotti W, Saraiva L, de Freitas N.M, et al. Efficacy of a herbal tooth paste on patients with established gingivitis–a randamised controlled trial. Braz Oral Res. 2006;20:172–7. [PubMed] CrossRef

- Sushma S, Nandlal B, Srilatha K.T. A comparative evaluation of a commercially available herbal and non-herbal dentifrice on dental plaque and gingivitis in children- A residential school based oral health programme. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2011;3:109–13.

- Mazumdar M, Chatterjee A, Majumdar S, Mahendra C, Patki P.S. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of complete care herbal toothpaste in controlling dental plaque, gingival bleeding and periodontal diseases. J Homeop Ayurv Med. 2013;2:1–5.

- Vyas Y.K, Bhatnagar M, Sharma K. In vitro evaluation of antibacterial activity of an herbal dentifrice against Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Indian J Dent Res 2008;19:26-8.

CrossRef - Sadhan A.I, Almas K A. Ra’ed I, and Miswak (chewing Stick): and Scientific Heritage 1999;80-8.

- Rahul R. Deshpande, Priyanka Kachare, Gautami Sharangpani, Vivian K. Varghese, Sneha S Bahulkar. Comparative Evaluation of Antimicrobial Efficacy of Two Commercially Available Dentifrices (Fluoridated And Herbal) Against Salivary Microflora. Int J Pharm Sci. 2014;6(6):72-74.