M. I. Ofili and B. P. Ncama

School of Nursing and Public Health, Howard College, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

*Corresponding Author E-mail: isiomamary@yahoo.com

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/450

Abstract

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is presently one of the most important risk factors for the development of cardiovascular diseases. In 2002, World Health Organization, (WHO), reported that hypertension causes one in every eight deaths worldwide making the disease the third killer in the world and more than 30 million people in Africa have hypertension. Hypertension increases the risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke and kidney dysfunction. Cultural perception has been identified to affect disease progression and management. Several developed and developing nations including Nigeria have adopted various initiatives to prevent and/or manage hypertension. However, the success of such strategies need to be constantly assessed and adjustments made if it becomes imperative.

Keywords

Hypertension; Heart; Kidney; High bloodpressure; Nigeria; Stroke

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Ofili M. I, Ncama B. P. Strategies for Prevention and Control of Hypertension in Nigeria Rural Communities. Biomed Pharmacol J 2014;7(1) |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Ofili M. I, Ncama B. P. Strategies for Prevention and Control of Hypertension in Nigeria Rural Communities. Biomed Pharmacol J 2014;7(1). Available from: http://biomedpharmajournal.org/?p=2834 |

Demography of Hypertension

Hypertension literarily means “High Blood Pressure”. (World Health Organization, 2002) defined it is as a persistent rise in blood pressure above what is considered normal for that age and that sex. It is a major public health problem in most African countries. (Graziano, 2005). It is the leading cause of death in developed and many developing countries being responsible for the deaths of 17 million people each year (World Health Organization, 2002). Hypertension affects approximately 50 million individuals in the United States and approximately 4 billion individuals Worldwide (Aram, George, & Henry, 2006). In Ghana, among urban adults, the prevalence of hypertension was 8% to 13% compared to 4.5% among rural adults (Muna, 1993). In a university community in South West Nigeria, the overall crude prevalence among a working population was 21% in the respondent population (Erhun, Olayiwola, & Agbani, 2005).

The latest estimate of the World Health Organization is that more than 30 million people in Africa have hypertension (Graziano, 2005). World Health Organization also predicts that if nothing is done about it by 2020, three quarters of all deaths in Africa will be attributable to hypertension (Graziano, 2005). The African Union has also called hypertension ’one of the continent’s greatest health challenges after HIV/AIDS (Graziano, 2005). Recent data from the Framingham Heart study showed the life time risk of hypertension to be approximately 90% for men and women who were non-hypertensive at 55 or 65 years and survived to age 80-85 years (Aram, et al., 2006).

Epidemiological evidence demonstrates a multifactorial cause for this condition with major risk factors including obesity, diet (specifically high sodium, low potassium and excess energy intake), stress and physical inactivity. Rural–urban migration coupled with acculturation and modernization has also been implicated in development of high blood pressure. The epidemiological studies conducted in Ghana and Kenya corroborates this finding. In a survey carried out in the rural community of Mamre, located in the Western Cape – South Africa, high prevalence of smoking, heavy alcohol use (in men), obesity (in women) and physical inactivity were reported as the major predictors/determinants of high blood pressure in the community. (Kaufman, Tracy, & Durazo – Arvizu, 1997). In this same survey, the prevalence of hypertension in people aged 15 years or more was 13.9% in men and 16.3% in women. Of the hypertension subjects, 27% were not aware of their hypertension, a further 14.4% were not on treatment and only 16.8% has blood pressure (BP) controlled below 140/90mm Hg.

A study published in 2003, showed a crude prevalence of 23.8% in the capital city of Accra, Ghana (Burket, 2006). (Lore, 1997) in what looks like an historical account stated that until the Second World War, normotension was the norm among many African countries like Kenya but about twenty-five years ago, high blood pressure became established in Kenya and the neighboring countries in particular Uganda. These trends were also observed in West Africa notably Ghana, Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Cameroon and Zaire in the central Africa region. (Lore, 1997). (Akinkugbe, 1996) in a cross-sectional study in Nigeria noted hypertension prevalence increase across the gradient from rural farmers to urban poor to railway workers as 14, 25 and 29 percent respectively. Also in a university community in southwest Nigeria, the overall crude prevalence among a working population was 21% in the respondent population (Erhun, et al., 2005). These trends if unchecked portend great danger for these developing countries. It is therefore easy to understand the worries over escalation of the disease and the health professionals’ efforts to checkmate its growth. The present study is part of that global effort.

Global Perspectives and Strategies for the Prevention and Control of High Blood Pressure

World-wide perspectives

Hypertension is ubiquitous, though the public health burden it represents relatively differs from country to country. Its ubiquity as a major public health problem was the justification for the World Conference 1995. There are many approaches to the prevention and control of hypertension in the world’s populations, and in most of these approaches, populations have roles to play. This conference has enabled the World Hypertension League (WHL) to obtain a global view of the approaches, difficulties and solutions associated with the prevention and control of hypertension, which should benefit all participants and societies. A review of selected national programs of hypertension control and cardiovascular disease prevention has shown the importance of mobilizing broad segments of the society, including medical and non-medical organizations, acting in partnership (Frohlich, 1995). Hypertension control programs must include provision for evaluation with regard to process and outcome as well as its impact on the levels of blood pressure of the populations or communities for which the programs are designed (Gy•rf•s & Strasser, 1995). Developing countries may need specific consideration in this regard and much can be achieved with modest means, if there is adequate societal support. Thus, hypertension control measures should be firmly based in primary health care. Health education, lifestyle counseling and screening programs especially in the rural settings can be powerful support measures.

The conclusions of the World Conference on Hypertension Control 1995 may be summed up as follows:

The goals of the World Hypertension League should continue to be emphasized and supported.

The establishment and building up of national leagues and societies in developing countries and in other countries with economic constraints needs particular attention.

The commitment of national leagues and societies to the control and prevention of hypertension should be stimulated. National societies concerned mainly with research on hypertension and the communication of research findings, may benefit from their programs practical aspects of hypertension control. Coalitions of national associations and leagues dedicated to hypertension prevention and control should be fostered, and should promote the concept of hypertension control as an important component of health promotion.

Co-operative international projects concerned with assessing the quality and impact of hypertension control programs or promoting the education of patients are concrete approaches to the advancement of hypertension control. Through such programs and similar activities, the World Hypertension League complements the International Society of Hypertension, the International Society and Federation of Cardiology and the World Health Organization.

By emphasizing that hypertension control programs should be continued with comprehensive cardiovascular health risk reduction, the World Hypertension League can contribute to the improvement of the health of the populations throughout the world.

Strategies for the Prevention and Control of High Blood Pressure

The prevention and control of high blood pressure no doubt would have a strong impact on the health, quality of life and mortality rate among rural communities in Nigerian. It would also reduce the health care expenditure needs of cardiovascular diseases.

Program Strategies

The short and long-term program outcomes will be achieved through the development and implementation of strategies involving both health and other developmental sectors. These strategies will address the behavioral and environmental factors associated with high blood pressure prevention and control in order to achieve three sub goals (prevention, early detection and control of hypertension). There are three main strategies namely: Community Health Promotion, Health Services System and System Support Strategy.

Theoretical Bases

The Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and Health Belief Model (HBM)

According to (Becker, 1974), the HBM hypothesizes that health-related action depends upon the simultaneous occurrence of three classes of factors

The existence of sufficient motivation (or health concern) to make health issues salient or relevant.

The belief that one is susceptible (vulnerable) to a serious health problem or to the sequel of that illness or condition.This is often termed perceived threat.

The belief that following a particular health recommendation would be beneficial in reducing the perceived threat, and at a subjectively-acceptable cost. Cost here refers to perceived barriers that must be overcome in order to follow the health recommendation; it includes, but is not restricted to financial outlays.

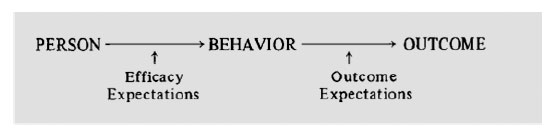

Bandura’s social learning theory (SLT), which he has been recently relabeled social cognitive theory (SCT) holds that behavior is determined by expectancies and incentives (Irwin, Victor, & Marshall, 1988). Behavior is regulated by its consequences (reinforcements), but only as those consequences are interpreted and understood by the individual. Thus, for example, in prevention and control of high blood pressure, individuals who value the perceived effects of changed lifestyles (incentives) will attempt to change if they believe that (a) their current lifestyles pose threats to any personally valued outcomes, such as health or appearance (environmental cues), (b) that particular behavioral changes will reduce the threats (outcome expectations) and (c) that they are personally capable of adopting the new behaviors (efficacy expectations).

Social cognitive theory has made at least two contributions to explanations of health-related behavior that were not included in the HBM. The first is the emphasis on the several sources of information for acquiring expectations particularly on the informative and motivational role of reinforcement and on the role of observational learning through modeling (imitating) the behavior of others. The delineation of sources of expectations suggests a number of potentially-effective strategies for altering behavior through modifying expectations. A second major contribution is the introduction of the concept of self-efficacy (efficacy expectation) as distinct from outcome expectation. Outcome expectation (defined as a person’s estimate that a given behavior will lead to certain outcomes) is quite similar to the HBM concept of ”perceived benefits”. The distinction between outcome and efficacy expectations is important because both are required for behavior. The diagram below from Bandura shows the relationship

For example, in prevention and control of hypertension, a man (person) is to quit smoking (behavior) for health reasons (outcome), he must belief both that cessation will benefit his health (outcome expectation) and also that he is capable of quitting (efficacy expectation).

This study adopted the HBM and SCT. This is because there are some ideas/concepts in the SCT that are not in the HBM which brings out the true picture of the study. Actually, a considerable overlap should be expected.

Philosophical Bases

Pragmatism and Community Empowerment

Pragmatism means for a layman the school of thought that insists on the relevance of practical consequences and values. The concept of any object should not be confused forgetting the concept of actual possible practical effects. In other words, reality should not be thwarted by digression, divergence and political rhetoric. Pragmatism is an empowerment in life as it instills wakefulness and relates life to here and now.

This study is focused on the potential of a pragmatist paradigm to empower a rural community by increasing their self efficacy and reducing the development of hypertension in that setting. Empowerment, in its most general sense, refers to the ability of people to gain understanding and control over personal, social, economic and political forces in order to take action to improve their life situations (Jenni, Frankish, & Glen, 2001). A critical element of community engagement relates to empowerment (mobilizing and organizing individuals, grass-roots and community-based organizations and institutions and enabling them to take action, influence and make decisions on critical issues). It is important to note that no external entity should assume that it can bestow on a community the power to act in its own self interest. Rather, those working to engage the community can provide important tools and resources so that community members can act to gain mastery over their lives.

First I will provide an overview of the empowerment concept both at the level of the individual, organization and community but focusing predominantly on community empowerment. Empowerment takes place at three levels: the (1) individual (2) organizational or group and (3) community levels (Rich, Edlestein, Hallman, & Wandersman, 1995); (Fawcett, Paine-Andrews, Francisco, & Vliet, 1993). Empowerment at one level can influence empowerment at the other levels (Fawcett, et al., 1995). At the individual level, it is generally referred to as psychological empowerment (McMillan, Florin, Stevenson, Kerman, & Mitchell, 1995);(Rich, et al., 1995). Individual level empowerment can be described along three dimensions: (1) intra-personal (an individual’s perceived personal capacity to influence social and political systems) (2) interactional (knowledge and skills to master the systems) and (3) behavioral (actions that influence the systems) (Rich, et al., 1995). This concept of psychological empowerment has been found to relate to an individual’s participation in organizations, the benefits of participation, organizational climate and the sense of community or perceived severity of problem.

At the group or organizational level, it distinguishes between (1) empowering organizations, which facilitate confidence and competencies of individuals and (2) empowered organizations, which influence their environment (Rich, et al., 1995). The degree to which an organization is empowering for its members may be dependent upon the benefits members receive and organizational climate as well as the levels of commitment and sense of community among members (McMillan, et al., 1995).

Community level empowerment (i.e. the capacity of communities to respond effectively to collective problems) occurs when both individuals and institutions have sufficient power to achieve substantially satisfactory outcomes (Rich, et al., 1995). Individuals and their organizations gain power and influence by having information about problems and an open process of accumulating and evaluating evidence and information (Rich, et al., 1995). Community empowerment focuses on the social contexts where empowerment takes place (Wallerstein and Bernstein, 1994).

Empowerment involves the ability to reach decisions that solve problems or produce desired outcomes requiring citizens and formal institutions working together to reach decisions (Rich, et al., 1995). In this light, if empowerment is defined as a continuous construction of a multi-dimensional participatory competence that encompasses both cognitive and behavioral changes (Fitzgerald, 2008), it shows the relationship between empowerment and pragmatist theory. That is, by the use of strategies such as engagement with subject matter, affective/ social learning strategies and pragmatist assessment and evaluation, learners can develop competence to bring about desired intellectual and life changes which can influence their particular learning communities. Thus the use of pragmatist learning strategies can help community members to develop the competence (and empowerment) they need to engage with their own learning communities fully.

Construction of knowledge must develop in a social context of communities and collaboration. Since all learners (community members) enter the process with different knowledge, backgrounds, experiences and cultural practices, a learning environment based on a combination of these two theoretical approaches can help to assure that each member can relate new concepts to existing knowledge in meaningful ways. Hence, in this study, empowering will encourage individuals to take more and greater responsibility for their own health issues, including community self reliance and self determination. The community members will have the right to determine their own needs and play an important role in the planning and delivery of health services. In doing this, the community workgroups who are seen as empowering.

engines in the community and serve as community organizations having leadership and system for communication will be needed. Community workgroups help to mobilize new groups and networks to search for new information, to search for knowledge required for problem solving, to manage problem solving and to influence the political and social environment in order to achieve a more supportive environment for social/political action and change.

Empowerment could also be seen as a process indicator. In this study, the community empowerment operational domains which has been modified by (Bush, Dover, & Mutch, 2002) will be discussed. The domains consist of four components 1) activation of the community 2) competence of the community in solving its own problems 3) program management skills and 4) ability of mobilizing resources (political, social, intellectual, financial and health). The activation of the community is understood as community members’ participation in community problem solving process, creation of community groups, leaders and networks and their involvement level and relationship quality. Competence of the community is defined as the knowledge and skills the community has to solve its problems, for problem-specific awareness, information dissemination skills and communication skills within and between groups. Program management skills are understood as the ability of the community groups to use evidence-based methods in identifying and solving their problems during program development, implementation and evaluation. Mobilizing resources is defined as the ability to invest in social, intellectual, political and financial capital. These operational domains represent those aspects of community empowerment that allow individuals and groups to organize and mobilize themselves towards commonly defined goals of political, social and health change (Laverack & Wallerstein, 2001).

Most authors have defined empowerment mainly as a process (Swift & Levin, 1987); (Wallerstein, 1992); (Rissel, 1994). It is understood as a process of increasing the ability of individuals, groups, organizations or communities to (1) analyze their environment (2) identify problems, needs, issues and opportunities (3) formulate strategies to deal with these problems, issues and needs and seize the relevant opportunities (4) design a plan of action (5) assemble and use effectively and on a sustainable basis resources to implement, monitor and evaluate the plan of actions and (6) use feedback to learn lessons (UNDP, 1995).

Community empowerment includes efforts to deter community threats, improve quality of life and facilitate citizen participation. The community empowerment model suggested by (Wallerstein, 1992) is multi-dimensional and includes the dimension of improved self-concept, critical analysis of the world, identification with the community members and participation in organizing community change (which is the main concept of this research study). In earnest, effective health interventions (for example guidelines for prevention and control of hypertension) require empowerment related processes and outcomes across multiple levels of analysis.

Conclusion

Hypertension control measures should be firmly based at primary level. The three main strategies (community health promotion, health services and system support strategy) for the prevention and control of high blood pressure no doubt would have a strong impact on the health, quality of life and mortality rate among rural communities in Nigeria. Epidemiological evidence demonstrates a multifactorial cause for this condition with major risk factors including obesity, diet (specifically high sodium, low potassium and excess energy intake), stress and physical inactivity. The theory of disease causation also known as the model of multiple causation discovers the causal relationship in order to understand why conditions (like hypertension) develop and offers effective prevention and protection. The application of pragmatism paradigm an empowerment in life, instills wakefulness and relates life to here and now. This is possible through community empowerment including community self reliance and self determination. The trend of this disease if unchecked especially in developing countries portend great danger.

References

- Akinkugbe, O. O. (1996). The Nigeria Hypertension Programme. Journal of Human Hypertension, 10(1), 43-46.

- Aram, V. C., George, I. B., & Henry, B. B. (2006). The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. United States: U.S Department of health and human services.

- Burket, B. A. (2006). Blood Pressure Survey in Two Communities in the Volta Region Ghana West Africa. Ethn Dis Winter, 16(1), 292-294.

- Bush, R., Dover, J., & Mutch, A. (2002). Community capacity manual. Melbourne: Centre for Primary Health Care, University of Queensland.

- Erhun, W. O., Olayiwola, G., & Agbani, E. O. (2005). Prevalence of Hypertension in a University Community in South West Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research, 8(1), 15-19.

- Fawcett, S. B., Paine-Andrews, A., Francisco, V. T., Schultz, J. A., Richter, K. P., Lewis, R. K., et al. (1995). Using empowerment theory in collaborative partnership for community health and development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 677-697.

- Fawcett, S. B., Paine-Andrews, A., Francisco, V. T., & Vliet, M. (1993). Promoting health through community development. In D. S. Glenwick & L. A. Jason (Eds.), Promoting health and mental health in children youth and families. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Fitzgerald, M. A. (2008). Empowerment and constructivism. Unpublished paper. St. Lawrence University Canton NY.

- Friedman, G. D. (1987). Primer of Epidemiology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Frohlich, E. (1995). Impact and interpretation of multiple guidelines and consensus documents. Journal of Human Hypertension, 10(1), 63-67.

- Graziano, T. A. (2005). The Financial Burden of Treating Hypertension in African Countries: A Cost Effective Analysis Comparing Two Approaches to Treating Hypertension in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Yaounde: Pan African Society of Cardiology

- Gy•rf•s, I., & Strasser, T. (1995). Lessons from worldwide experience with hypertension control. Journal of Human Hypertension, 10(1), 21-25.

- Jenni, J., Frankish, C. J., & Glen, M. (2001). Setting standards in the evaluation of community-based health promotion programmes- a unifying approach Health Pronmotion International, 16(4), 367-380.

- Kaufman, J. S., Tracy, J. A., & Durazo – Arvizu, R. A. (1997). Lifestyle Education and Prevalence of Hypertension in Populations of African Origin. Annals of Epidemiology, 7(1), 22-27.

- Laverack, G., & Wallerstein, N. (2001). An identification and interpretation of the organizational aspects of community empowerment. Community Development Journal, 36(2), 40-52.

- Lore. (1997). Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases in Africa with Special Reference to Kenya: An Overview. East Africa Medical Journal, 70(6), 357-361.

- McMillan, B., Florin, P., Stevenson, J., Kerman, B., & Mitchell, R. E. (1995). Empowerment praxis in community coalitions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 699-728.

- Muna, W. F. (1993). The Importance of Cardiovascular research in Africa today. Ethnicity and disease, 4(2), 8-12.

- Rich, R. C., Edlestein, M., Hallman, W. K., & Wandersman, A. H. (1995). Citizen participation and empowerment: the case of local environmental hazards. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 657-676.

- Rissel, C. (1994). Empowerment: The holy grail of health promotion. Health Promotion International, 9(1), 39-47.

- Swift, C., & Levin, G. (1987). Empowerment: An emerging mental health technology. Journal of Primary Prevention, 8(1), 71-94.

- UNDP. (1995). Capacity Development for Sustainable Human Development: Conceptual framework and operation signpost. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- Wallerstein, N. (1992). Powerlessness empowerment and health: Implications for health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion, 3(6), 197-205.

- World Health Organization. (2002). The World Health Report:Reducing Risks, Promoting Health Life Geneva: World Health Organization.