Rahee Borulkar* and Priti Dhande

and Priti Dhande

Department of Pharmacology, Bharati Vidyapeeth Medical College and Research centre, Dhankawadi, Pune, India

Corresponding Author E-mail:borulkar10@gmail.com

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/3115

Abstract

Background: Medication reconciliation (MedRec) is an often-neglected area when it comes to patient safety, which can prove detrimental to patients and put a strain on healthcare professionals. Awareness of this concept is important to improve and maintain the quality of patient care. Objective: To study the knowledge, practice and perception of health care workers regarding medication reconciliation and procedure evaluation in a tertiary care hospital in Pune. Methods: The study was conducted in three phases. The first phase assessed the knowledge, practice and perception (K, P, P) of 124 healthcare professionals in relation to MedRec using a questionnaire and the process of MedRec in a tertiary care hospital. The second phase involved the application of interventions to improve the K, P, P of healthcare staff and the MedRec process and the third phase was the re-evaluation of the above parameters. Results: The first phase of assessing participants' K, P, P showed less impressive results, especially for residents, followed by care managers. The MedRec process at admission was just 49%. However, the scenario changed in the post-intervention phase when the knowledge, perception and practice of all participants improved significantly (P ≤ 0.05). Participants showed improved knowledge, with over 90% answering correctly after the interventions, which also enhanced their practices and perceptions. An improvement was also observed in overall medication reconciliation where 74% cases had complete documentations of medications at admission, suggesting that the interventions were actually fruitful. Conclusion: Knowledge, perception and practice of healthcare workers regarding MedRec does have an impact on the procedure itself and hence it is important to be aware regarding the process to provide a good quality of patient services.

Keywords

Errors; Knowledge; Medication; Practice; Patient-safety; Reconciliation

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Borulkar R, Dhande P. Medication Reconciliation: An Exemplary Approach to Augment and Improve Patient Safety. Biomed Pharmacol J 2025;18(1). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Borulkar R, Dhande P. Medication Reconciliation: An Exemplary Approach to Augment and Improve Patient Safety. Biomed Pharmacol J 2025;18(1). Available from: https://bit.ly/3QqcPDD |

Introduction

Medication errors are the most common problem that a medical professional is regularly confronted with. Inadequate history when admitting patients, insufficient knowledge of medication, overworked medical staff, poor communication between doctors and patients are the main factors responsible for the occurrence of errors.1 A study of 400 discharged patients found that 66% of adverse drug events occurred, of which 13% were preventable if a proper patient and medication history was documented.2 It is therefore obvious that medication errors are one of the main causes of adverse events. Worldwide, medication review and reconciliation are two common methods for preventing errors. WHO defines medication reconciliation (MedRec), “A formal process of establishing and documenting a consistent, definitive list of medicines across transitions of care and then rectifying any discrepancies.”1 Simply put, medication reconciliation is a process of documenting the patient’s medications for their existing comorbidities and considering them when prescribing newer medications for their current condition. There are three MedRec checkpoints: on admission, on transfer from one site to another and on discharge.

MedRec often becomes a negligible event in patient care. This is due to a lack of awareness and interest on the part of healthcare professionals and improper practice methods, and this vicious circle continues. MedRec is a complex process and in the case of patient management, a fragmented organization is unacceptable. It has been observed that doctors spend a considerable amount of their time on administrative tasks. Therefore, it is essential to cultivate medication reconciliation as an important part of patient care and not as a tedious documentation task.3,4 The indifferent attitude of doctors and personal disinterest in MedRec, unable to keep up with the process due to their daily clinical commitments, lead to an increase in discrepancies in medication ordering. A constructive alliance between physicians, residents, nurses and clinical pharmacists with proper task assignment and clear responsibilities of each

party will enhance the co-ordination process and establish a workflow that is beneficial to the hospital. Nevertheless, the hierarchy factor should not be an obstacle to the implementation of the reconciliation process. Each team member has a moral responsibility to inform each other of discrepancies and correct them.

Finally, the information provided by patients in MedRec is important. It is important that the history of medications taken by patients is accurate, as it is crucial for further treatment. Considering these factors, this study was conducted to test the knowledge, practice and perception of hospital staff regarding medication reconciliation and the detection of discrepancies in the MedRec process at the study site. In addition, interventions were implemented to determine whether the above parameters improved.

Materials and Methods

A prospective intervention study was conducted from October 2020 to July 2022 in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Pune. The study population included physicians from department of Medicine & Intensive care unit, Residents of department of Medicine, Surgery & Anesthesia and Nursing in-charges. Approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Bharati Vidyapeeth Medical College, Pune (Approval: BVDUMC/IEC/88) was obtained. The study was divided into three parts. The first part was evaluating medication reconciliation process via case-file audit of comorbid patients in departments of Medicine and Intensive care units of the hospital and assessment of knowledge, perception and practice of healthcare workers using a questionnaire as study tool in January-February of 2021. The questionnaire was created after an extensive literature search and was pre-tested & pre-validated before commencement of the study. After obtaining informed consent from participants via the Google form itself, the questionnaire was filled by them. The second part was to apply interventions and observe change in MedRec process as well as knowledge, perception and practice of participants from March 2021 to October 2021. The interventions applied were training session of study participants to educate them in depth about the process of medication reconciliation and their continuous sensitization via educational posters containing information about MedRec in wards and out-patient departments from time to time so the lacunae in their knowledge and practice methods could be acknowledged. The study participants were asked to proactively interact with clinical pharmacists and vice versa, whenever discrepancies were identified by either of the party. Another set of interventions included educating patients through informative pamphlets with the help of nurses and acquainting them about the importance of communicating their medication list. The third part was to re-evaluate the MedRec process and knowledge, practice and perception of healthcare workers in November-December 2021. The study population was finalized on basis of the fact that the mentioned departments are exposed to a greater number of patients suffering from co-morbidities and the rate of discrepancies discovered in these patients is high.

Statistical analysis: The data is expressed in frequencies and percentages. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS software, version 21. Chi-square test was applied to observe difference in medication reconciliation process before and after interventions and for comparison of the responses by participants before and after the interventions. One-way ANOVA was used to observe improvement in each parameter in all the designation of the study population.

Results

The study population involved 124 healthcare personnel from various departments and of different designations. The designations of participants were first and second year post-graduate residents (JR1 AND JR2), Consultants and Nursing in-charges (Figure 1). Their knowledge, practice and perception regarding medication reconciliation was tested before and after the application of interventions.

|

Figure 1: Distribution of study participants according to their designationsClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 2: Comparison of Knowledge of study participants regarding MedRec before and after interventions.Click here to view Figure |

(*the results were significant if p ≤ 0.05)

The questions for knowledge section were as follows: (Correct answer presented in bold)

Q1. Are you familiar with the concept of Medication reconciliation? (Yes/No)

Q2. Who is responsible to complete Medical reconciliation process? (Options: Doctor, Nurses, Clinical pharmacists)

Q3. Are you aware about the current existing policy in your hospital for MedRec? (Yes/No)

Q4. Within what time frame should MedRec be completed after patient admission (Options: 12 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours)

Q5. Within what time frame should MedRec be done in patients who are on high risk drug? (Options: 6 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours?

Figure 2 depicts the responses by participants to 5 questions about knowledge of medication reconciliation. The majority of participants (93%) had some prior knowledge of medication reconciliation, which rose to 97% after interventions; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Prior to interventions, only 79% of respondents knew that it is the doctor’s duty to finish the MedRec process; this number dramatically increased to 93% (p= 0.002) after. The participants were questioned regarding their knowledge of the hospital’s medication reconciliation policy. 84% of them knew about the hospital’s MedRec policy prior to the intervention, and in the post-intervention phase, nearly all of them knew about the policy significantly [n (%) = 121(98 percent); p=0.00]. Hospital policy states that a patient’s medication reconciliation must be finished within 24 hours of their admission. Just 52% of respondents were aware of this rule prior to interventions. The response changed significantly as a result of the interventions, going from 52% to 93% (p= 0.00). The final knowledge category question asked participants if they knew the precise window of time for high-risk medications. 70% of participants were aware of the precise period of time during the pre-interventional stage. In the post-interventional phase, 96% of participants knew the precise window of time for high-risk medications (p= 0.00).

The comparison of study participants’ practice methods (Q6–9) and perceptions (Q10–13) regarding medication reconciliation before and after interventions is displayed in Table 1. 92% of the participants reported having attended formal medication reconciliation training, and following interventions, every participant acknowledged having attended the medication reconciliation training session (p= 0.001). In both study phases, all participants inquired about their patients’ medication histories when they arrived for medical attention. Just 22.5 percent of participants believed that more than 50% of patients take their prescribed medications as directed when asked what proportion of patients voluntarily give the doctor their list of medications prior to interventions. Following interventions, a shift in perspective was noted, with 64.5% of study participants stating that more than half of patients gave their medication list to their doctors. According to our hospital policy, healthcare professionals are required to record the MedRec process on an initial assessment form, so documentation on the proper document is essential. Only 75% of participants had written down their medications on the expected document prior to interventions; this number dramatically increased to 93% following the application of interventions (p= 0.00014). Participants were questioned about who they believed should be in charge of medication reconciliation when a patient is being transferred. Before the interventions, only 58% of participants thought that doctors should be in charge of it, and 41% thought that clinical pharmacists should be in charge. Following the interventional phase, this perception was considerably altered, with 91% of study participants agreeing that a doctor has a duty to finish MedRec when transferring a patient (p= 0.000). In both study phases, participants unanimously agreed that medication reconciliation should occur at the time of discharge. In addition, participants were asked to rate the usefulness of the medication reconciliation process. Across both phases, over 70% of healthcare professionals thought MedRec was an extremely beneficial procedure. Every participant concurred that reducing patient harm is possible through medication reconciliation.

Table 1: Comparison of Practice & Perception of participants regarding MedRec pre And post intervention (n = 124)

| Questions | Response options | Pre-Interventionn (%) | Post-Interventionn (%) | Chi-square P value |

| Attended formal training at work on role in medication reconciliation? | Yes | 114 (91.9) | 124 (100) | 0.001* |

| No | 10 (8.06) | 0 (0) | ||

| Do you routinely ask patients for a current list of medications when they arrive in your service? | Yes | 124 (100) | 124 (100) | – |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Percentage of patients communicate to you regarding current and chronic list of their medications when they arrive in your service? | <10% | 14 (11.29) | 0 (0) | Not applicable |

| 10-30% | 63 (50.8) | 19 (15.3) | ||

| 30-50% | 19 (15.3) | 25 (20.1) | ||

| >50% | 28 (22.5) | 80 (64.5) | ||

| Type of form is your medication reconciliation process documented on patient admission? | Initial assessment form | 93 (75) | 115 (92.74) | 0.00014* |

| Medication chart | 31 (25) | 9 (7.2) | ||

| Responsibility of reconciling medications upon transfer? | Physicians | 72 (58.06) | 113 (91.1) | 0.000* |

| Clinical Pharmacist | 52 (41.93) | 11 (8.8) | ||

| Are medications needed to be reconciled on discharge? | Yes | 124 (100) | 124 (100) | – |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Rate your perception of medication reconciliation as a valuable process for patient safety | Valuable | 34 (27.41) | 25 (20.16) | Not applicable |

| Very Valuable | 90 (72.5) | 99 (79.8) | ||

| Do you think Medication reconciliation will lead to reduction in patient harm? | Yes | 124 (100) | 124 (100) | – |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

(*the results were significant if p ≤ 0.05)

To determine which group of study participants had performed better in each category, an intergroup analysis was carried out using One Way ANOVA. For every study group, the pre- and post-interventional scores were acquired for every category of knowledge, practice, and perceptions. The scores of these groups were then compared to determine which performed better.

The pre- and post-interventional total knowledge scores are shown in Table 2, along with a comparison of them. The consultants’ group had the highest knowledge score during the pre-intervention phase, while the first year post-graduate residents’ group had the lowest (p <0.001). Every group showed a noteworthy progress, with first-year post-graduate residents showing the greatest improvement, followed by second-year post-graduate residents, nursing in-charges, and consultants (p <0.001). Before and after interventions, the relative change in scores was computed. Comparing these scores, it was found that the consultants’ group had the lowest score difference and the first junior resident group had the largest score difference between pre- and post-intervention knowledge. When the scores were compared between the groups, there was a significant difference (p= 0.003).

Table 2: Change in mean total Knowledge score pre & post intervention of participants regarding MedRec using One-way ANOVA test (n=124)

| Groups | Pre-intervention scores | Post-intervention scores | Difference in score |

| Consultants | 4.64± 0.48 | 4.93±0.26 | 0.0007±0.001 |

| First year post graduate residents | 3.23±1.4 | 4.84±0.4 | 0.0064±0.009 |

| Second year post graduate residents | 3.77±1.0 | 4.9±0.3 | 0.0047±0.007 |

| Nursing in-charges | 3.78±0.9 | 4.35±0.7 | 0.001±0.002 |

| Significance of change in score (p value) | < 0.001* | <0.001* | 0.003* |

(*the results were significant if p ≤ 0.05)

The comparison of the total practice scores acquired during the pre- and post-interventional phases is displayed in Table 3. During the pre-intervention phase, the consultants’ group had the highest practice score, while the second year post-graduate residents had the lowest (p = 0.004). All groups showed improvement, with second year post-graduate residents showing the greatest improvement, followed by first year post-graduate residents, nursing in-charges, and consultants. Nevertheless, the improvement was not statistically significant (p= 0.084). Pre-and post-intervention scores were compared to determine the relative change in scores. Comparing these scores, it was found that the consultants’ group had the lowest difference in score and the second year post-graduate resident group had the largest difference in pre- and post-intervention practice scores. When comparing scores within groups, there was a significant difference (p = 0.03).

Table 3: Change in mean total Practice score pre & post intervention of participants regarding MedRec using One-way ANOVA test (n=124)

| Groups | Pre-intervention scores | Post-intervention scores | Difference in score |

| Consultants | 2.96± 0.18 | 3.00±0.00 | 1.7±9.4 |

| First year post graduate residents | 2.58±0.6 | 2.91±0.2 | 23.2±52.7 |

| Second year post graduate residents | 2.50±0.5 | 2.97±0.1 | 26.66±40.9 |

| Nursing in-charges | 2.7±0.47 | 2.83±0.38 | 6.5±17.21 |

| Significance of change in score (p value) | 0.004* | 0.084 | 0.03* |

(*the results were significant if p ≤ 0.05)

The total perception scores acquired during the pre- and post-interventional phases are shown in Table 4, along with a comparison of them. During the pre-intervention phase, the group of consultants had the highest perception score, while the group of nursing in-charges had the lowest (p= 0.003). All groups showed a significant improvement, with second year junior residents showing the greatest improvement (p = 0.01), followed by consultants, first year post-graduate residents, consultants, and nursing in-charges. Pre- and post-intervention scores were compared to determine the relative change in scores. When these scores were compared, the first post-graduate resident group showed the largest difference in score between pre- and post-intervention perception, while the consultants’ group showed the lowest difference. When comparing scores within groups, there was a significant difference (p = 0.02). Based on these findings, it can be inferred that although the consultants had good knowledge, practice, and perception of medication reconciliation even prior to the application of interventions, the post-graduate residents in the study had only fair knowledge, practice, and perception of it, followed by nurses. The group of residents has significantly improved with the application of interventions in all questionnaire categories, particularly in first-year residents’ knowledge and second-year residents’ practice.

Table 4: Change in mean total Perception score pre & post intervention of participants regarding MedRec using One-way ANOVA test (N=124)

| Groups | Pre-intervention scores | Post-intervention scores | Difference in score |

| Consultants | 1.86± 0.3 | 1.96±0.1 | 10.7±31.4 |

| First year post graduate residents | 1.49±0.5 | 1.93±0.2 | 44.1±50.2 |

| Second year post graduate residents | 1.6±0.4 | 1.97±0.18 | 36.6±49.01 |

| Nursing in-charges | 1.39±0.49 | 1.74±0.44 | 34.78±48.69 |

| Significance of change in score (p value) | 0.003* | 0.01* | 0.02* |

(*the results were significant if p ≤ 0.05)

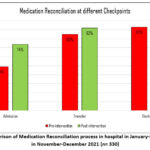

Moving on to the assessment of the medication reconciliation process, information was gathered from case files, and an audit was carried out in January–February 2021, prior to the interventions being implemented, as well as in November–December 2021, following their completion. The records of medication reconciliation completed at the time of the patient’s admission, during their transfer between hospital locations, and upon their discharge were evaluated in the files. Before the interventions, 51% of patient admission case files did not have medication reconciliation documentation. Following interventions, there was a noticeable shift in that 74% of case files had documentation for medication reconciliation at the time of admission (Figure 3). In the pre-intervention phase, transfer reconciliation was 85%, and this percentage improved in the post-interventional phase as well, with 92% of case files having comprehensive medication documentation. Ninety-three percent of case files had MedRec documentation during discharge, prior to interventions, and ninety-five percent of case files had it after. No medication documentation was observed because approximately 5% of patients in the post-intervention phase and 4% of patients in the pre-intervention phase did not survive.

|

Figure 3: Comparison of Medication Reconciliation process in hospital in January-February 2021 & in November-December 2021 (n= 330).Click here to view Figure |

Discussion

When it comes to providing high-quality patient care, Medication reconciliation has long been misinterpreted as being inconsequential. Having said that, those who are aware only possess a partial understanding of MedRec, which results in incorrect procedures leading to subpar patient care. Medication errors typically have a negative impact overall and have been shown to decrease with implementation of MedRec. Thus, it is imperative that healthcare professionals understand the concept of reconciliation and incorporate it into their daily responsibilities. The study evaluates knowledge, practice and perception regarding Medication Reconciliation of the doctors, residents and nurses, spots the lacunae and determines the measures required to enhance their capabilities via various effectual interventions. Along with this, the study also gauges the process of medication reconciliation in hospital and impact of healthcare workers’ knowledge, practice and perception on the MedRec process.

We compared the findings of our study with those of earlier research on related topics. Al-Hashar attempted to assess the extent to which physicians, nurses, and clinical pharmacists were knowledgeable about medication reconciliation. They found that physicians were aware of their primarily responsibility for completing the various tasks involved in the MedRec process. Furthermore, according to 81 percent of nurses, doctors must confirm the list and obtain a proper and accurate history of the patient’s medications. In our study, 70% of nurses claimed that during admission, doctors should reconcile any differences between the prescribed medication order and the medication history list. However, the many doctors in our study were not aware of this fact during pre-interventional phase. After comparing our findings with those of Al-Hashar5 our study has revealed yet another instance of a knowledge and communication gap among healthcare workers, with many of them being ignorant of the role of the physician in the MedRec process.

Boockvar assessed pharmacists’ and resident physicians’ perceptions of medication reconciliation. In addition to doubting the legitimacy of the process, study participants saw reconciliation primarily as an administrative procedure with minimum impact on patient care. In contrast, every member of our healthcare team felt that MedRec does, in fact, contribute to less patient harm.6 Physicians in the aforementioned study stated that, in comparison to other sections of the medical record, medication reconciliation documents are not as trustworthy sources of prescribing information. In light of this, depending on the patient’s condition, it is required to update the medication information at each checkpoint. Majority of our study participants were not aware of the appropriate document on which the admission reconciliation needed to be recorded prior to interventions.

Seliman M Ibrahim, evaluated knowledge, attitude and practice of physicians, pharmacists and nurses in a tertiary hospital. According to their study, 70% of physicians and about 80% of both pharmacists and nurses knew about medication reconciliation. In comparison to this overall 93% of our study participants knew about MedRec even before interventions. In Seliman M Ibrahim, et al study, when asked about existence of medication reconciliation policy in their hospital, 75% of their nurses were aware about the policy while only 58.5% of physicians responded to this question.7 In our study prior to interventions, 72% of 1st year junior residents, 87% of 2nd year residents and 78% of nurses knew about existence of MedRec hospital policy which improved post intervention to 100%, 97% and 100% respectively.

The World Health Organization prepared a document called “The High 5 Standard operating protocol assuring medication accuracy at transition in care: Medication reconciliation” which states that the best possible history should be obtained during admission and that reconciliation should be finished within 24 hours.8 Of first- and second-year residents, only 46% and 47%, respectively, were aware of obtaining the history and finishing the MedRec process within a day. The hospital MedRec policy mentions the 24-hour rule, but 52% nurses were also unaware of it.

During the preliminary stage of our intervention, a staggering 50% of our healthcare professionals claimed that less than half of the patients under their care shared their medication list. In order to delve deeper into this matter, Gionfriddo conducted a comprehensive evaluation by personally interviewing these healthcare workers. Astonishingly, 39% of the participants revealed that patients rarely carried their medication list with them, while 46% confirmed that patients did present their medication list. Surprisingly, 12% of the healthcare workers believed that patients brought their medications from home.9

However, after implementing our intervention, a remarkable transformation occurred. In the post-intervention phase, an impressive 64% of our dedicated participants reported that more than half of the patients now communicate their current medication list. This positive outcome showcases the effectiveness of our intervention in improving patient communication and medication reconciliation.

Upon acquiring a deeper understanding of the knowledge, perception, and practice of our healthcare professionals, the subsequent course of action involved assessing the medication reconciliation procedure in our hospital. A meticulous examination of case files during the preliminary phase highlighted a deficiency in the reconciliation process upon patient admission, in contrast to transfer and discharge, thus warranting immediate enhancement. Tahir and colleagues implemented a series of interventions in their comprehensive study, meticulously assessing the intricate process of medication reconciliation. They diligently educated their healthcare professionals, enlightening them on the importance of engaging in meaningful discussions regarding patients’ medication regimens with both the patients themselves and their families. To ensure the utmost adherence to this crucial task, constant reminders were provided to the residents to carry out the reconciliation. Furthermore, visual cues in the form of pamphlets were attached on the ward’s bullpen, reminding residents of their duty. The process was further enhanced by the providing informative posters, while appointment cards, included a gentle reminder for patients to bring their medications along to every appointment. These meticulously designed interventions exemplified the noble pursuit of enhancing patient care and safety even though the magnitude of the changes occurring were not significant.10 Our interventions, which followed a similar approach to the aforementioned study, yielded superior outcomes in comparison. We witnessed an improvement in admission reconciliation, with rates increasing from 49% to 74%.

In a study by Ouchida, they implemented a series of interventions that were seamlessly integrated into the medical students’ curriculum. These interventions included engaging multidisciplinary lectures, informative video demonstrations of medical procedures, and thought-provoking group discussions. The results were truly remarkable, as the students exhibited a significant improvement in their knowledge, attitude, and behaviour towards MedRec.11 Throughout our study, we observed a notable enhancement in the knowledge, practice, and perception of our healthcare staff following the implementation of educational strategies.

Clinical pharmacists play a pivotal role in the intricate process of medication reconciliation, by seamlessly applying their acquired knowledge on the current subject, in their day-to-day practice. In a study conducted by Dong, the impact of pharmacist-led intervention on medication reconciliation was examined. These skilled pharmacists not only imparted training to physicians but also embarked on a retrospective journey of medication reconciliation for a duration of two weeks, following the completion of the initial process by the physicians themselves. The outcome of this intervention was nothing short of astounding, as the percentage of geriatric patients encountering unintentional medication discrepancies upon admission witnessed a decline from an alarming 55.3% to a significantly improved 25.3%.12 Clinical pharmacists have a significant impact on medication reconciliation, as shown by our research as well. Quélennec found that 87.9% of medication discrepancies in patient admission were regrettable omissions of prescribed drugs. They uncovered these inconsistencies within 24 to 48 hours through patient interviews and medical history. The collaboration of physicians and pharmacists successfully identified deviations and reduced potential harm.13 Our study revealed that there were no instances of remote or potential patient harm detected during both the pre and post intervention phases. This can be attributed to the attentive oversight provided by our clinical pharmacists, who play a crucial role in ensuring patient safety. Such attention to detail is a standard practice at our esteemed hospital, in accordance with our MedRec policy.

It is of utmost importance that medication reconciliation is executed promptly and with utmost precision. Not only does it ensure the safety of the patient, but it also provides doctors with valuable insights for their subsequent treatment plans. The allocation of a certain amount of time towards MedRec has proven to enhance the quality of patient safety services in numerous hospital environments over an extended period. The integration of reconciliation into the regular practice of every physician is imperative, as it leaves no space for inadequate information or communication among healthcare professionals. This, in turn, leads to a clear understanding of individual responsibilities resulting in favourable outcomes for the patients.

Limitations

The study consisted of limited number of departments and hence the results cannot be generalised to other speciality fields. Similarly, the study was conducted in only one tertiary set up which does not take into consideration the aspect of medication reconciliation in other hospitals in the city or the state. More studies are required to explore the root cause of the unawareness in regards to Medication reconciliation amongst healthcare workers and find shortcomings in their practice of the same.

Conclusion

The process of medication reconciliation stands as a crucial element in ensuring the safety of patients, and our research substantiates this fact by illustrating how alterations in healthcare workers’ understanding, implementation, and viewpoint on MedRec can impact the reconciliation process. Our study demonstrated that how lack of awareness and improper practice methods can have an impact on reconciliation process. However, by implementing appropriate interventions, it is feasible to achieve substantial enhancements in the knowledge, practices, and perceptions of healthcare professionals, which will subsequently benefit the medication reconciliation process.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude for the unwavering dedication and tireless efforts exhibited by the clinical pharmacists who played an integral role in this study. Furthermore, they extend their heartfelt appreciation to all the study participants for their unwavering cooperation and invaluable contributions throughout the entirety of this research endeavor.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

We have obtained internal ethics committee approval. Approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Bharati Vidyapeeth Medical College, Pune (Approval: BVDUMC/IEC/88)

Informed Consent Statement

Consent was obtained from the study population who were eligible to participate prior to commencement of knowledge survey. The permission to utilise the patient records was obtained from hospital authorities before commencement of data collection.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials

Author contributions

- Dr Priti Dhande: The concept of medication reconciliation and the establishment of the standard operating procedure were introduced by Dr. Priti.

- Dr Rahee Borulkar: Data collection, statistical analysis, and the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Technical Series on Safer Primary Care: Medication errors; 2016 Accessed August 13, 2024. who.int. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511643

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The Incidence and Severity of Adverse Events Affecting Patients after Discharge from the Hospital. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(3):161.

CrossRef - Westbrook JI, Ampt A, Kearney L, Rob MI. All in a day’s work: an observational study to quantify how and with whom doctors on hospital wards spend their time. Medical Journal of Australia. 2008;188(9):506-509.

CrossRef - Dresselhaus TR, Luck JV, Wright B, Spragg RG, Lee ML, Bozzette SA. Analyzing the time and value of housestaff inpatient work. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13(8):534-540.

CrossRef - Al-Hashar A, Al-Zakwani I, Eriksson T, Al Za’abi M. Whose responsibility is medication reconciliation: Physicians, pharmacists or nurses? A survey in an academic tertiary care hospital. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2017;25(1):52-58.

CrossRef - Boockvar KS, Santos SL, Kushniruk A, Johnson C, Nebeker JR. Medication reconciliation: Barriers and facilitators from the perspectives of resident physicians and pharmacists. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2011;6(6):329-337.

CrossRef - Ibrahim S, Khawla Abuhamour, Farah Abu Mahfouz, Hammad E. Hospital Staff Perspectives toward Medication Reconciliation: Knowledge, Attitude and Practices at A Tertiary Teaching Hospital in Jordan. Jordan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2021;14(2). Accessed August 13, 2024. https://archives.ju.edu.jo/index.php/jjps/article/view/108002

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Patient Safety Solutions Aide Memoire Assuring Medication Accuracy at Transitions in Care.; Accessed August 13, 2024. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/patient-safety/patient-safety-solutions/ps-solution6-medication-accuracy-at-transitions-care.pdf?sfvrsn=8cc90bc8_6

- Gionfriddo MR, Duboski V, Middernacht A, Kern MS, Graham J, Wright EA. A mixed methods evaluation of medication reconciliation in the primary care setting. Shen L, ed. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0260882.

CrossRef - Tahir H, Ramagiri Vinod N, Daruwalla V, et al. Decreasing Unintended Medication Discrepancies in Medication Reconciliation through Simple Yet Effective Interventions. American Journal of Public Health Research. 2017;5(2):30-35.

CrossRef - Ouchida K, LoFaso VM, Capello CF, Ramsaroop S, Reid MC. Fast Forward Rounds: An Effective Method for Teaching Medical Students to Transition Patients Safely Across Care Settings. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(5):910-917.

CrossRef - Dong PTX, Pham VTT, Nguyen LT, et al. Impact of pharmacist‐initiated educational interventions on improving medication reconciliation practice in geriatric inpatients during hospital admission in Vietnam. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2022;47(12):2107-2114.

CrossRef - Quélennec B, Beretz L, Paya D, et al. Potential clinical impact of medication discrepancies at hospital admission. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2013;24(6):530-535.

CrossRef