Manuscript accepted on :14-12-2024

Published online on: 29-12-2024

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Nina Mariana and Dr. Shoheb Shaikh

Second Review by: Dr. Ayan Chatterjee

Final Approval by: Dr. Patorn Promchai

Thikra Hilal Hamed Al Dhuhli1, Ruwaida Nasser Abdulla AL-Lamki2 and Mohamed Mabruk1*

and Mohamed Mabruk1*

1Department of Biomedical Science, Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman

2Department of Microbiology, Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman

Correspondong Author E-mail: mabruk@squ.edu.om

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/3064

Abstract

Bacteriuria is common in pregnancy and is associated with the risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality. In Oman, no studies have been done to determine the percentage of symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant Omani patients. This study investigated the prevalence and incidence of antibiotic resistance patterns of symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria among pregnant Omani women. A total of 230 urine samples were collected from symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant Omani female patients. Clinical patient information was gathered from the Hospital Information System (HIS). Bacterial pathogens were identified in the urine samples using microscopic examination, cultures, and serological techniques. Antibiotic sensitivity tests were performed on the isolated bacterial pathogensBacteriuria was found in 14 (6.08%) of the 230 urine samples. Among the 14 bacteriuria-positive samples, 6 were symptomatic (2.06%) and 8 were asymptomatic (3.47%). The most common bacteria were Escherichia coli (35.71%) and Streptococcus agalactiae (21.43%). Most of the clinical isolates were completely resistant to ampicillin. Asymptomatic bacteriuria was more common than symptomatic bacteriuria in the pregnant Omani population. The detection of antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria, especially in asymptomatic pregnant Omani women, underscores the importance of implementing strict guidelines for the prevention of this public health issue. This includes advising and encouraging pregnant women to follow strict hygiene protocols to avoid Urinary tract infection (UTI) during pregnancy, as this type of infection may have adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

Keywords

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria; Antibiotic Resistance; Pregnancy; Symptomatic Bacteriuria

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Al Dhuhli T. H. H, AL-Lamki R. N. A, Mabruk M. Microbiological and Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern Among Pregnant Women in The Sultanate of Oman: Comparison Between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. Biomed Pharmacol J 2024;17(4). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Al Dhuhli T. H. H, AL-Lamki R. N. A, Mabruk M. Microbiological and Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern Among Pregnant Women in The Sultanate of Oman: Comparison Between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. Biomed Pharmacol J 2024;17(4). Available from: https://bit.ly/40bKKWec |

Introduction

Bacteriuria is the manifestation of bacterial pathogens in the urine with and without causing apparent clinical manifestations1,2 Biologically, the urinary tract is sterile and designed to prevent infections3. The bladder and ureters are structured to stop urine from backing up toward the kidneys. The flow of urine during urination washes bacteria out of the urinary tract4 However, infections can still occur because of some influencing factors, such as variations in the host’s natural defense mechanisms, premenopausal and menopausal factors and age2. Urinary tract infection (UTIs) may result in serious complications such as cystitis, urethritis, and pyelonephritis5. Symptomatic and asymptomatic UTIs result in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes2.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is a subclinical infection that is existing in cases where the urine culture shows a bacterial pathogen growth of higher than 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per ml of urine and without apparent UTI clinical manifestations in the patient1 . Proper management of asymptomatic bacteriuria can decrease its incidence by 80%–90% 6,7,8

The causative agent that accounts for more than 80% of all UTIs during pregnancy is Escherichia coli9. Other causes include Proteus mirabilis, , Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Klebsiella pneumoniae 3,8,9.

A previous study in Nigeria on urine samples obtained randomly from 125 pregnant patients, showed that 40% of patients were positive for bacteriuria10. Another study in the United Arab Emirates showed that the highest rate of infection among symptomatic pregnant UTI patients was with E.Coli followed by Group B streptococcus 11. The percentage of bacteriuria is high in pregnant women due to many factors12. One factor is women’s immune status during pregnancy. Pregnant women are considered immunocompromised UTI hosts8. . Other factors include the physical and hormonal changes1,8,12. For example, during pregnancy, there is a great increase in fluid discharges, which enhance bacterial growth. In addition, progesterone stimulates urethral smooth muscle resting, causing urinary stasis, which is significant in the etiology of cystitis9,13. During pregnancy, the urine pH reaches an appropriate level for E. coli growth13.

Undetected asymptomatic bacteriuria is linked to unfavorable obstetric and fetal outcomes, because of the increased chance of its progression to symptomatic bacteriuria 14,15. Therefore, screening and management of bacteriuria during pregnancy are essential to avoid UTI these adverse effects3.

The aims of the present study were to investigate the prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria Omani among pregnant women and to identify the causative bacterial pathogens, and finally to determine the antibiotic resistance patterns of the bacterial pathogens isolated from this unique group of patients.

Materials and Methods

Specimens

Detection of pathogenic bacteria in urine by routine culture

Microscopic examination of the urine samples was carried out by loading 60 μL of each urine sample into microtiter plate wells. Then, the urine specimens were examined under an inverted light microscope for the detection of epithelial cells, casts ,crystals, white and red blood cells. A UTI was diagnosed by bacterial culture. All the urine specimens were inoculated aseptically using a bacteriological 3 mm loop on cysteine lactose electrolyte deficient agar (CLED).

Following inoculation of the urine samples on CLED agar, the agar plates were incubated at 37˚C for 24 hours. The results were reported depending on the shape and number of colonies. The colonies were counted to determine the degree of significance, which depended on the loop size used. Only plates with more than 11 colonies were reported as significant. When three or more types of bacterial colonies were present, the sample was reported to have urogenital contamination. The CLED agar plates were examined for the presence of yellow or green colonies, which may indicate the presence of lactose-fermenting or non-lactose-fermenting bacteria.

Pathogenic bacteria identification and antibiotic sensitivity tests

Biochemical identification of the pathogenic microorganisms in the urine samples and antibiotic sensitivity tests of the isolated bacterial pathogens were carried out for suspected colonies using the BD Phoenix™ 100 (Becton Dickinson, USA). The bacteria isolated from the urine samples were suspended in 0.85% NaCl and diluted to 0.5 McFarland. Then, they were loaded into specific panels and analyzed using the BD Phoenix™ 100.

Detection of Streptococcus agalactiae

S. agalactiae detection in the urine samples was conducted using the Alere BinaxNOW® Streptococcus agalactiae Antigen Card (Abbott, USA), which is a rapid assay for the qualitative detection of S. agalactiae (Group B Streptococci) antigen in a patient’s urine sample. The test was carried out by immersing a swab in the urine sample, and then the swab was inserted into the card. The reagent was added to the swab, and the result appeared after 15 minutes. If two lines appeared (control and test), a positive result was indicated. Positive samples by Alere BinaxNOW® Streptococcus agalactiae Antigen Card were confirmed by the isolation of S. agalactiae, followed by antibiotic sensitivity testing.

Data analysis

All patient data were collected and tabulated using the Excel program (Excel 2013). . SPSS software.

Results

Clinical features

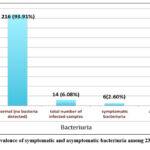

Of the 230 urine samples analyzed, 216 (93.91%) samples were negative for bacteriuria, while 14 (6.03%) samples were positive. The 14 samples were categorized according to the patients’ symptoms into symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria. Table 1 shows the symptoms of the symptomatic bacteriuria patients; some symptomatic patients showed more than one clinical manifestation [Table 1]. The most common observed clinical manifestations were dysuria followed by lower abdominal pain [Table 1]. Six symptomatic patients (2.06%) were positive for bacteriuria, while eight asymptomatic patients (3.47%) were positive for bacteriuria. [Figure 1], shows the rate of symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria among the 230 isolated samples.

Table 1: Symptoms that appeared in symptomatic bacteriuria patients (Total number of symptomatic bacteriuria patients (14). Some patients showed more than one clinical manifestation)

| UTI Symptoms | Number of cases |

| Dysuria | 5 |

| Lower abdominal pain | 2 |

| Fever | 1 |

| Urinary Frequency | 1 |

| Flank pain | 1 |

Identity and prevalence of bacterial pathogens in symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria

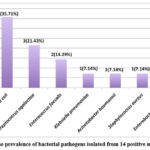

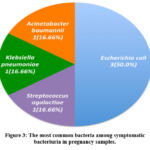

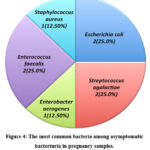

The most common bacterial pathogen isolated from the samples of the 14 pregnant patients with bacteriuria was E. coli. Figure 2, shows the prevalence of the bacterial pathogens detected in the 14 positive urine samples obtained from both the symptomatic and the asymptomatic pregnant women. E. coli was identified in 5 (35.71%) patients, followed by S. agalactiae (Group B Streptococci), in 3 patients (21.43%) and Enterococcus faecalis in 2 patients (14.29%). K. pneumoniae, Acintobacter baumannii, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterobacter aerogenes were each detected in one patient (7.14%). The most common bacteria identified in the urine samples obtained from the symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women are shown in [Figures 3 & 4].

|

Figure 1: The prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria among 230 urine samples. |

|

Figure 2: The prevalence of bacterial pathogens isolated from 14 positive urine samples |

|

Figure 3: The most common bacteria among symptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy samples. |

|

Figure 4: The most common bacteria among asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy samples. |

Antibiotic susceptibility

The results of the antibiotic sensitivity tests for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and E. aerogenes are shown in [Table 2]. These bacteria were all sensitive to meropenem, while E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii were resistant to ampicillin [Table 2]. Table 3 presents the antibiotic sensitivity test results for Group B streptococci (S. agalactiae), which was fully sensitive to linezolid, vancomycin, and penicillin [Table 3]. Table 4 shows the S. aureus antibiotic sensitivity test results, indicating complete sensitivity to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, tetracycline, linezolid, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Table 5 demonstrates the antibiotic sensitivity of the two samples with E. faecalis, which were completely sensitive to ampicillin, linezolid, and vancomycin and completely resistant to tetracycline and erythromycin.

Table 2: Antibiotics sensitivity test results for Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acintobacter baumannii and Enterobacter aerogenes.

| Bacterial

Strains |

N (%) | AMP | |||||||

| E.coli | 5 (35.71%) | 0 | 75% | 80% | 60% | 100% | 80% | 60% | 75% |

| K.pneumoniae | 1(7.14%) | 0 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| A.baumannii | 1(7.14%) | 0 | 100% | 100% | 0 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| E.aerogenes | 1(7.14%) | 100% | 0 | 100% | 0 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

AMX = Ampicillin; CIP = Ciprofloxacin; ERY = Erythromycin; LZD = Linezolid; TNC = Tetracycline; TEI = Teicoplanin; VAN = Vancomycin; CRO = Ceftriaxone; CXM = Cefuroxime; SXT = trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; AMK = amikacin; IMP = Imipenem; MEM = Metropenem

Table 3: Antibiotics sensitivity test results for Streptococcus agalactiae

| Bacterial

Strains |

N(%) | CLI | ERY | LZD | PNC | TNC | VAN |

| S. agalactiae | 3(21.43%) | 33.3% | 33.3% | 100% | 100% | 0 | 100% |

AMX = Ampicillin; CIP = Ciprofloxacin; ERY = Erythromycin; LZD = Linezolid; TNC = Tetracycline; TEI = Teicoplanin; VAN = Vancomycin; CRO = Ceftriaxone; CXM = Cefuroxime; SXT = trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; AMK = amikacin; IMP = Imipenem; MEM = Metropenem

Table 4: Antibiotics sensitivity test results for Staphylococcus aureus

| Bacterial

Strains |

N(%) | AMP | PNC | CIP | ERY | TNC | TMP/SMX | LZD | IMP |

| S. aureus | 1(7.14%) | 0 | 0 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0 |

AMX = Ampicillin; CIP = Ciprofloxacin; ERY = Erythromycin; LZD = Linezolid; TNC = Tetracycline; TEI = Teicoplanin; VAN = Vancomycin; CRO = Ceftriaxone; CXM = Cefuroxime; SXT = trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; AMK = amikacin; IMP = Imipenem; MEM = Metropenem

Table 5: Antibiotics sensitivity test results for Enterococcus faecalis

| Bacterial

Strains |

N (%) | AMP | CIP | ERY | LZD | TNC | TEI | VAN |

| E.faecalis | 2(14.29%) | 100% | 50% | 0 | 100% | 0 | 100% | 100% |

AMX = Ampicillin; CIP = Ciprofloxacin; ERY = Erythromycin; LZD = Linezolid; TNC = Tetracycline; TEI = Teicoplanin; VAN = Vancomycin; CRO = Ceftriaxone; CXM = Cefuroxime; SXT = trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; AMK = amikacin; IMP = Imipenem; MEM = Metropenem.

Discussion

In this study, among the 230 urine samples collected from pregnant Omani female patients admitted to Sultan Qaboos University Hospital and screened for bacteriuria, only 14 (6.08%) cases were positive for the presence of bacteriuria. Among the 14 positive samples, 6 (2.06%) of the symptomatic pregnant patients were positive for bacteriuria, while 8 (3.47%) of the asymptomatic pregnant patients were positive for bacteriuria. These findings are comparable to a study conducted in Saudi Arabia, where 419 (15.8%) out of 2642 cases were positive for the presence of bacteriuria15. Of the 419 positive subjects, 188 (7.1%) subjects were asymptomatic for bacteriuria, and 231 (8.7%) were symptomatic15.

In the present study the most common symptoms seen in symptomatic patients were dysuria followed lower abdominal pain. These findings were in contrast to previously published study in United Arab Emirates were lower abdominal pain was the most common followed by dysuria11.

In the existing study, E. coli (35.71%) was the most frequent cause of bacteriuria in both the asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant patients. This finding is consistent with studies carried out in Saudi Arabia and UAE respectively, where E. coli was the most common contributing agent to bacteriuria11,15. The detection of E. coli can be explained by the difficulty in maintaining hygiene during pregnancy9. In addition, in pregnancy, urine pH reaches a level appropriate for E. coli growth9. Conversely, the results are inconsistent with a study conducted in Brunei, where the leading cause of bacteriuria in pregnancy was Klebsiella spp. (2.94%), followed by E. coli16. In our study, the most common bacterial pathogens present in the symptomatic bacteriuria patients after E. coli (35.71%) were S. agalactiae, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii (all 16.66%). The most common bacterial pathogens present in the asymptomatic bacteriuia patients after E. coli (25.00%) were S. agalactiae (25.00%), E. faecalis (25.00%), S. aureus (12.50%), and E. aerogenes (12.50%).

In the present study the isolated E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii were all completely resistant to ampicillin. This finding is coherent with a study performed in India, where most of their isolates were highly resistant to ampicillin17. This suggests that ampicillin should not be used as a first line of defense against UTIs in pregnancy in Oman. In the present study, Imipenem and meropenem were sensitive for most of the clinical isolates, so they might provide effective alternatives for treatment. In the present study Group B streptococci (S. agalactiae), was fully sensitive to linezolid, vancomycin, and penicillin. This finding is constant with previously published studies 11,18,19,20 . Antibiotic over Prescribing for UTI results in the emerging of antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens.21 Asymptomatic bacteriuria caused by antibiotic resistant organisms is alarming and screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy is of great importance to avoid adverse maternal and fetal outcomes22.

Conclusion

Our data suggest asymptomatic bacteriuria is more predominant than symptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant patients in Muscat, Oman. E. coli, S. agalactiae, and E. faecalis were the most common contributors to bacteriuria in pregnant women in Muscat, Oman. The outcomes of this investigation provide valuable understanding into the dynamics between symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. In addition, the present study shows the importance of frequent urine testing during pregnancy for early detection and treatment of UTI. Also, the present study shows the need for implementing new guidelines to prevent UTIs during pregnancy, with special reference to educating and encouraging pregnant women on the importance of personal hygiene in preventing UTIs during pregnancy and ultimately, preventing any adverse effect on the developing fetus.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Microbiology Department, SQUH for their support.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics statement

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials

Author contributions

Thikra Hilal Hamed Al dhuhli; Methodology, Analysis, Review;

Ruwaida Nasser Abdulla AL-Lamki: Supervised-Methodology, Review;

Mohamed Mabruk: Conceptualization, Design Supervision , Review-Editing.

References

- Ansaldi Y, de Tejada Weber BM. Urinary Tract Infection in Pregnancy. Clin Microbiol & Infect. 2023; 29(10): 1249-1253

CrossRef - Chelkeba L, Fanta K, Mulugeta T, and Melakucorresponding T . Bacterial profile and antimicrobial resistance patterns of common bacteria among pregnant women with bacteriuria in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obste.2022; 306(3): 663–686.

CrossRef - Al-Badr A & Ghadeer G. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections Management in Women: review. SQU Med J. 2013; 13 (3) :359– 367.

CrossRef - Najar, M, Saldanha C and Banday K. Approach to urinary tract infections. Indian J. Nephrol 2009; 19(4):129.

CrossRef - Heyns C. Urinary tract infection associated with conditions causing urinary tract obstruction and stasis, excluding urolithiasis and neuropathic bladder World J. Urol. 2011; 30(1):77-83. .

CrossRef - Siakwa M, Ankobil A, Hansen- Owoo. E. Pregnancy Outcomes: A Comparison of Women with Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Cape Coast, Ghana. African J Preg & Childbirth 2014; 2(2): 27-30.

- Alghamdi A, Almajid M, Raneem, A, Mjad A, Alghamdi I. Evaluation of asymptomatic bacteruria management before and after antimicrobial stewardship program implementation: retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis; 2021; 21: 869.

CrossRef - Flores-Mireles A., Walker J, Caparon M and Hultgren S. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Rev. Microbiol. 2015; 13(5):269-284.

CrossRef - Bien J, Sokolova O, Bozko Role of Uropathogenic E.Coli Virulence Factors in Development of Urinary Tract Infection and Kidney Damage. Int. J. Nephrol.2012; 1-15.

CrossRef - Ajayi AB, Nwabuisi C, Aboyeji AP, Ajayi NS, Fowotade A, Fakeye O. Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Antenatal Patients in Ilorin, Nigeria. Oman Med J 2012; 27(1):31–35.

CrossRef - Dube R, Al-Zuheiri STS, Syed M, Harila L, Zuhaira AL, Kar SS. Prevalence, Clinico-Bacteriological profile and antibiotic resistance of symptomatic Urinary tract infections in pregnant women. Antibiotics 2023; 12(1) 33:1-12.

CrossRef - Kline K, Schwart D, Gilbert N, Lewis, A. Impact of Host Age and Parity on Susceptibility to Severe Urinary Tract Infection in a Murine Model. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(5) :e97798.

CrossRef - Macejko AM, Schaeffer AJ. Asymptomatic bacteriuria and symptomatic urinary tract infections during pregnancy. Clin. North Am 2007;34(1) :35-42.

CrossRef - Kehinde, A, Adedapo K, Aimaikhu, C, Odukogbe A, Olayemi O. and Salako B. Significant Bacteriuria Among Asymptomatic Antenatal Clinic Attendees In Ibadan, Nigeria. Trop Med & Health 2011; 39(3) :73-76.

CrossRef - Abduljabbar H, Moumena R, Mosli H, Khan A, Warda, A. Urinary Tract Infection in Pregnancy. Ann Saudi Medicine 1991; 11(3):322-324.

CrossRef - Muharram, S, Ghazali S, Yaakub H, Abiola O. A Preliminary Assessment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria of Pregnancy in Brunei Darussalam. Malaysian J of Med Sci 2018; 21(2):34-39.

- Sujatha R. Prevalence of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria and its Antibacterial Susceptibility Pattern Among Pregnant Women Attending the Antenatal Clinic at Kanpur, India. J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8(4): 1–3.

- Balachandran L, Jacob L, Al Awadhi R, Yahya LO, Catroon KM, Soundararajan LP, Wani S, Alabadla S, Hussein YA. Urinary Tract Infection in Pregnancy and Its Effects on Maternal and Perinatal Outcome: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2022; 14, e21500.

CrossRef - Al-Zuheiri ST, Dube R, Menezes G, Qasem S. Clinical profile and outcome of Group B streptococcal colonization in mothers and neonates in Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates: A prospective observational study. Saudi Med. J 2021; 9, 235–240

CrossRef - Basu A , Sanyal A , Bhattacharyya K. A Clinico-microbiological Study of Urinary Tract Infections in Pregnant Women attending Antenatal Clinic of a Tertiary-level Hospital with Special Reference to Antimicrobial Sensitivity. Afro-Egypt . J Infect Endem Dis, 2024;14(1):61-74.

- Ghouri F, Hollywood A.. Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care for Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) in Pregnancy: An Audit Study. Med Sci (Basel). 2020 Sep 17;8(3):40.

CrossRef - Alenazi AM, Taher IA, Taha AE, Elawamy WE, Alshlash AS, El-Masry EA, Ghazy AA. Pregnancy-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria and antibiotic resistance in the Maternity and Children’s Hospital, Arar, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2023 Dec 31;17(12):1740-1747.

CrossRef