Siti Nor Aqilah Mohd Noor1 , Umar Idris Ibrahim1

, Umar Idris Ibrahim1 , Shazia Jamshed2

, Shazia Jamshed2 , Nurulumi Ahmad1

, Nurulumi Ahmad1 , Aslinda Jamil1

, Aslinda Jamil1 , Rosliza Yahaya3

, Rosliza Yahaya3  and Pei Lin Lua1*

and Pei Lin Lua1*

1Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kampus Besut, Besut, Terengganu, Malaysia,

2School of Pharmacy, International Medical University (IMU), Bukit Jalil, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia,

3Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kampus Perubatan, Jalan Sultan Mahmud, Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia

Corresponding Author E-mail:peilinlua@unisza.edu.my

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/3015

Abstract

Depression remains a major global health crisis, impacting millions worldwide. The swift progression of digital health technology has intensified interest in employing mobile health (mHealth) applications to tackle mental health concerns, particularly depression. mHealth applications for depression management constitute a groundbreaking method, providing globally scalable and accessible solutions that can significantly enhance mental health care. This study sought to assess the existing evidence about the utilization and effectiveness of mHealth applications in the management of depressive symptoms. Studies were identified by literature searches in three electronic databases (Scopus, Science Direct, and PubMed) from 2000 to 2024. Studies were chosen according to a set of inclusion criteria and reviewed narratively (n = 21). Research indicates that six studies investigated the prevalence of depression, whereas twelve studies emphasized the function and features of mHealth applications in symptom management. Significant enhancements in mental health outcomes were documented in seven studies (n = 7), showing the efficacy of these programs in engaging users and reducing depressive symptoms. The primary limitations of current mHealth literature are: 1) focus on screening rather than follow-up care; 2) limited accessibility; 3) insufficient user engagement; 4) small sample sizes; 5) absence of cost-effectiveness statistics; and 6) inconsistent app quality. To address these challenges, the focus must be directed toward optimal application design and enhanced accessibility. All these research gaps are crucial to be overcome for advancing evidence-based solutions and empowering the digital health sector to improve mental health outcomes for this cohort.

Keywords

Depression; Depression Screening; Digital Health; Mhealth; Mobile Application

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Noor S. M. A. M, Ibrahim U. I, Jamshed S, Ahmad N, Jamil A, Yahaya R, Lua P. L. Bridging the Gap: The Promise and Pitfalls of Mobile Health Apps for Depression Management. Biomed Pharmacol J 2024;17(4). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Noor S. M. A. M, Ibrahim U. I, Jamshed S, Ahmad N, Jamil A, Yahaya R, Lua P. L. Bridging the Gap: The Promise and Pitfalls of Mobile Health Apps for Depression Management. Biomed Pharmacol J 2024;17(4). Available from: https://bit.ly/41MWW0D |

Introduction

Depression is a mental health disorder affecting more than 280 million people worldwide1. Depression is a major factor contributing to the increasing prevalence of mental health issues globally. The high occurrence of this issue is especially concerning since it significantly affects people’s overall well-being, limiting their ability to do daily activities, disturbing their professional and personal connections, and potentially causing severe harm to their physical and mental health. It significantly influences the child’s daily functioning, quality of life, and increases the risk of suicide, particularly among young adult2. As a result of COVID-19, the need for easily accessible mental health interventions has increased, and depression rates have risen worldwide3.

In response to the increasing demand for mental health services, mobile health (mHealth) technology has become essential for delivering prompt and accessible therapies4. These technologies, particularly via smartphone applications, provide scalable solutions that address traditional healthcare gaps by offering mental health services to individuals from diverse environments and backgrounds5. mHealth applications provide self-monitoring, prompt assistance, and tailored feedback, so empowering users to actively participate in the management of their mental health6. Moreover, internet-based mental health treatment offers significant benefits, such as improved accessibility to services regardless of location, sustained care via remote assistance, and financial savings for healthcare systems7.

As mHealth tools continue to progress, digital interventions are increasingly essential to modern mental healthcare. Mental health applications are progressively integrating screening instruments, cognitive behavioural treatment (CBT) methodologies, and mood monitoring, all aimed at being accessible and user-friendly8. This accessibility is essential for those in rural or underserved regions and corresponds with the global initiative for more inclusive mental health solutions9. This study seeks to explore the prevalence of depression, assess the potential of digital health technologies, and evaluate the efficacy of mHealth applications in enhancing mental health outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This brief review was performed using comprehensive literature searches across three electronic databases: Scopus, Science Direct, and PubMed, encompassing the period from 2000 to 2024. The search for pertinent research utilized the terms “depression,” “mental health,” “depression screening,” “mHealth,” and “mobile application.” Boolean operators like ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were employed to enhance the search for both sensitivity and specificity.

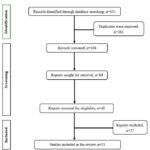

The studies discovered through this search were subjected to manual review for inclusion. Eligible studies were required to fulfil the following criteria which could be either quantitative or qualitative, published in English, freely accessible, and especially focused on the utilization of mobile applications for depression screening. Studies were omitted if they were review articles, did not directly investigate depression in relation to mobile applications, or largely addressed stress or anxiety instead of depression. A simplified flow summary is presented in the selecting process (Figure 1).

This study employed a narrative methodology to offer a comprehensive synthesis of research investigating the utilization and efficacy of mHealth applications in the management of depressive symptoms. The focus was directed towards research assessing the application of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) screening instrument in mobile applications, user engagement, and mental health outcomes across various demographics. No formal statistical analysis was conducted; rather, the collected material was qualitatively evaluated to discern patterns and obstacles associated with the utilization of mobile applications for depression management.

|

Figure 1: Flow summary of the article Click here to View Figure |

Results and Discussion

Prevalence and Impact of Depression

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) reports that at least 3.8% of the global population is affected by depression. Of this, 5% are men, 6% are women, 5.7% are individuals over 60 years old, with the global number of depressed people reaching approximately 280 million. Prevalence is nearly 50% higher among women than men. Moreover, over 10% of pregnant women and new mothers suffer from depression10. Every year, over 700,000 people commit suicide, making it the fourth leading cause of death among people aged 15 to 29. Depression contributes to 7.5% of all disability-adjusted life years (YLDs) worldwide and is the leading cause of disability globally1.

In Malaysia, surveys done recently have pointed out the rise in depression among the youth and the teachers, in detail. For example, the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) of 2019 reported that 2.3% of Malaysians suffer from depression11, while educators are more prone to depression due to job pressure12. Research indicates that 43% of secondary school teachers in Klang displayed symptoms of depression, underscoring the mental health burden on Malaysian educators13.

The global prevalence of depression among teachers has worsened due to the pandemic. Research in Chile indicated that 67% of educators exhibited depression symptoms during the pandemic, highlighting the mental health challenges faced by educational sectors globally14. In addition, a global study found that 35.4% of educators experienced depression symptoms15. In Kazakhstan, depression affected 46% of faculty members in medical colleges, emphasizing its widespread impact16. Similarly, in Spain, 32.2% of educators in the Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre exhibited depressive symptoms, reflecting the significant prevalence of depression in the teaching profession17.

Therefore, there is a need to promote timely and sustainable mental health support by using effective, scalable interventions like mHealth apps (Table 1).

Table 1: Prevalence of depression.

| Reference | Sample Size/Population | Method | Prevalence of depression | Country |

| 12 | n=70Academics from International Medical University, IMU | · Self-reported Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)· Randomized controlled trial | 32.9% | IMU, Malaysia |

| 13 | n= 356Six secondary school teachers | · Malay version of DASS-21 | 43.0% | Klang, Malaysia |

| 14 | n= 313Primary & secondary school teachers | · Self-reported DASS-21· Cross-sectional study | 67.0% | Chile |

| 15 | n=381Teachers from schools, colleges & universities | · Self-reported DASS-21· Cross-sectional web-based survey | 35.4% | Bangladesh |

| 16 | n=596Educators from 6 large medical universities from different regions. | · Self-reported DASS-21· A quantitative observational cross-sectional study | 40.6% | Kazakhstan |

| 17 | n=1633Teachers from the department of education in the Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre | · Spanish version of DASS-21 | 32.2% | North of Spain |

The Features of Digital Health in Depression Screening

The role of mobile health applications in mHealth is pivotal since they have received massive public attention and have been developed rapidly to address mental health issues globally. Many mobile health applications incorporate tools like the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a widely used screening instrument for depression, offering several advantages such as easy access, privacy and cost-effectiveness18,19. Furthermore, mobile apps are expected to lift the weight of many obstacles that would stand in the way of the promotion mental health services20. It has been recognized that mobile applications for screening, diagnosing, and providing treatment, as well as creating awareness about mental health issues such as depression, and anxiety, are among the most promising, cost-effective, and engaging tools available today21. What’s more, mobile health apps are simple and easy to use, require very little time input, can be used at any hour, and the elimination of social fear makes them a favorite among users, making them an excellent mental health resource20.

Studies from various countries have demonstrated the potential of these mobile apps in mental health. For example, a study in the Philippines found that the ability of mobile phone software programs to adapt has allowed professionals from various fields of science and medicine to collect physiological information from the patients thus facilitating the screening, diagnosis, and treatment22. An Australian study of the same type indicated that the use of the app Mood Prism, which is centered on reflection, leads to better mental health, as well as life satisfaction21. Similarly, in the UK, it was determined that the introduction of mobile health applications brought about a significant change in stress management practices and overall well-being of individuals over time23. The Happy Mother app in South Korea enhanced health-promoting activities and ameliorated depressive outcomes in postnatal moms24. In the USA (Massachusetts), the Mindset for Depression app, employing cognitive behavioural treatment (CBT), demonstrated great feasibility and acceptability among individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD)25.

The researchers have concluded that young people will likely accept mental health apps. The studies have given preference to the prototype of the mental health app, whereas the young Icelanders have used the app for a long time26. A feasibility study on the Personalized Real-time Intervention for Motivational Enhancement (PRIME) app, designed for individuals with recent-onset schizophrenia, demonstrated that mobile interventions offering social engagement and goal-sharing opportunities within a recovery framework are effective treatment strategies for young people with schizophrenia27. In addition, in Canada, a trial of the mobile application (DeStressify) among universities has found it to be useful to students who were struggling to cope with the stigma associated with mental health issues20. Furthermore, a different study has indicated that a mobile health app was able to guide some users in the appropriate direction for the diagnosis of depression19.

Another very important factor is that these can keep users engaged due to personalized feedback. Research has shown that user-tailored feedback based on individual characteristics is better than standardized feedback23, 28. Applications of machine learning (ML) algorithms can guide users in their mental health journeys using these apps29. By utilizing machine learning algorithms and behavioral data, these apps can offer customized recommendations that guide users through their mental health care journey29 (Table 2).

Table 2: The features of digital health in depression screening and management

| Feature | Description | Benefit | Reference |

| PHQ-9 Screening Tool | Incorporates Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),Widely uses as depression screening tool | Enables easy and accessible depression assessment | 18,19 |

| Accessibility | Mobile health apps are simple to use, require minimal time, available anytime, and reduce social fears, making them highly accessible and appealing | Widens outreach and reduces stigma | 20 |

| Adaptability | Apps can be tailored for different professional and local needs, enabling data collection and enhancing accessibility across demographics. | Guarantees relevance across various populations | 22 |

| Self-Reflection and Life Satisfaction | Apps like Mood Prism encourage user self-reflection, which is linked to better mental health and life satisfaction. | Facilitates self-reflection and insight | 21 |

| Stress management | Mobile health applications as demonstrated in UK-based studies contribute:- improved stress management- Enhanced well-being when used regularly | Promotes resilience in stress management | 23 |

| Postnatal Depression Support | Apps, such as the Happy Mother app, promote health-positive activities and reduce depressive symptoms in new mothers. | Facilitates postnatal well-being | 24 |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Apps incorporating CBT techniques, like the Mindset for Depression app, are feasible and well-received for addressing major depressive disorder (MDD). | Offers accessible, organized therapeutic assistance | 25 |

| Youth Mental Health Engagement | Apps are well accepted among young people, with studies showing long-term engagement and positive impacts on youth mental health. | Promotes mental health awareness among youth or adolescents | 26, 27 |

| Stigma Reduction | Apps like DeStressify help reduce mental health stigma, particularly among university students. | Reduces stigma, promoting candid discussions about mental health. | 20 |

| Guidance Toward Diagnosis | Some mobile health apps direct users toward professional mental health diagnosis, providing an accessible path to formal treatment. | Encourages professional help-seeking | 19 |

| Personalized Feedback | Tailored feedback based on individual characteristics has been shown to improve user engagement and treatment outcomes compared to standardized feedback. | Enhances engagement and effectiveness | 23, 28 |

| Machine Learning Integration | Machine learning algorithms enable apps to provide personalized recommendations and guidance throughout users’ mental health journeys, | Offers a customized care experience | 29 |

Effectiveness of mHealth apps

mHealth apps are versatile and helpful in various settings. In a study evaluating the “Mindset for Depression” app, 93% of users expressed their readiness to recommend the app to others, while significant improvements in mood and significant reductions in depressive symptoms were detected25. The “Health Monitor App”, which employs the PHQ-9 to screen for depression, has demonstrated high accuracy in recognizing users with high depressive symptoms in different countries19. In Europe, the Kelaa Mental Resilience App was proven to be the most effective for enhancing workplace mental health and stress management23. Another study conducted in South Korea revealed that the “Happy Mother App” was the most beneficial alleviating postpartum depression symptoms among new mothers24.

The DeStressify app, utilized by university students in Canada, significantly mitigates mental health stigma by offering a friendly forum that promotes candid discussions regarding mental health. This application has demonstrated considerable potential in assisting students in managing the adverse views linked to mental health difficulties, therefore fostering a more positive mental perspective20. Moreover, the PRIME application, intended for persons with recent-onset schizophrenia, proved effective in engaging youth through its social and goal-sharing functionalities within a recovery-focused paradigm. It provides an efficacious mental health intervention technique that fosters users’ social relationships and goal attainment, both crucial for recovery27.

mHealth applications have gained prominence owing to their capacity to deliver tailored and accessible mental health care, particularly in regions where conventional mental health services are insufficient. They provide advantages of scalability, cost efficiency, and anonymity, giving them attractive tools for mental health interventions30. Research demonstrates that customized health communications, conveyed via mHealth applications, can enhance engagement and yield superior mental health results compared to generic messages28. Nonetheless, despite its prevalent application, obstacles persist, including data privacy issues and the digital divide, which may restrict accessibility for some demographics31.

Although these studies emphasize the immediate advantages of mHealth applications, further investigation is needed to determine their long-term efficacy in the management of mental health disorders. Nonetheless, the research indicates that mHealth applications possess significant promise for tackling mental health challenges on a broad scale, especially in resource-limited areas. The digital format facilitates personalized therapies, hence augmenting their efficacy in mental health care32. In conclusion, mHealth applications signify a promising opportunity for enhancing mental health outcomes, providing accessible and user-friendly platforms to tackle depression, anxiety, and various mental health difficulties across multiple contexts (Table 3).

Table 3: Effectiveness of mHealth Apps on Mental Health

| Reference | App/Intervention | Mental Health Condition | Population/Setting | Key Findings |

| 25 | Mindset for depression | Depression | Massachusetts, individuals with Major Depressive Disorder | 93% of users would recommend the app; significant improvement in mood and depressive symptoms |

| 19 | Health Monitor App | Depression | · United States (US)· Canada· United Kingdom (UK)

· New Zealand · Australia |

Among 2,538 individuals, 322 indicated major depressive symptoms, resulting in a 74% completion rate for follow-up and 38% seeking professional assistance. |

| 23 | Keela Mental Resilience App | StressMental health | · Europe, workplace setting (employees) | Enhanced stress management, overall well-being, and sleep quality among employees |

| 24 | Happy Mother App | Postpartum depression | South Korea(new mother) | The app demonstrated considerable effectiveness to improve health-promotion behaviours among mothers, suggesting that prolonged usage may further reduce depressive outcomes. |

| 20 | DeStressify | Canada | The utilization of DeStressify shown a significant reduction in trait anxiety (P=.01) and enhancement in overall health (P=.001), energy (P=.01), and emotional well-being (P=.01) among university students. | |

| 27 | PRIME | Schizophrenia | United StatesCanadaAustralia | PRIME is a viable, acceptable, and effective technique for enhancing mood and motivation in adolescents with a severe mental disorder. |

| 28 | N/A | Depression | Resident of Australia(60 years of age and above) | Tailored messages delivered through applications were read more often, remembered more effectively, and regarded as more pertinent. |

Limitations of the Current Literature

Despite the promising results of mHealth apps, several gaps remain. First, many mHealth apps focus predominantly on screening, with less emphasis on facilitating follow-up care. For example, although the Health Monitor App successfully diagnosed users with depression, merely 38% of them pursued assistance from a professional doctor19. This split between screening and the provision of treatment indicates an urgent necessity for better care alternatives, which could be included in the app. Another problem with these tools is that they may be inaccessible to a broad range of potential users. Many applications are available in just 1 or 2 languages, and they often fail to consider the cultural aspects leading to different demographic groups. In addition, the majority of mHealth apps are designed for individual users, with little emphasis on integrating support from mental health professionals or social networks, which could be vital to ensuring better outcomes.

Furthermore, a few limitations were recognized, especially insufficient app engagement, which prevented a comprehensive evaluation of its efficacy in enhancing mental health outcomes24. They underscored the necessity for more regular changes to app material to ensure relevance, as well as the absence of communication options between users and mental health professionals, which constrained the app’s support functionalities. The brief duration of the trial hindered the assessment of long-term impacts, and the exclusion of iPhone users from the study undermined the random sampling method, hence impacting the generalizability of the results.

Additionally, many studies have small sample sizes, which limits the generalizability of findings. For example, the study on the “Mindset for Depression” app utilized a limited sample group, perhaps unable to represent the program’s efficacy across other ethnicities25. Likewise, the evidence on the cost-effectiveness of these technologies is also scant, more particularly in low-resource conditions, when the population may be deprived of smartphones and the internet. Otherwise, the quality, and design of mHealth apps are not constant and several studies on the specific characteristics that lead to the efficacy of these applications, differentiating things like user interface, engagement strategies, or feedback mechanisms have been rather few.

Future Directions

In the future, research should aim at overcoming the inadequacies and drawbacks that are currently present in this area of study. To better the functionality and usability of mHealth applications, the designers of these solutions should make it their priority to integrate follow-up care within the application such as telehealth consultations or automated referral systems. In addition, the endeavour to come up with apps that are culturally sensitive, and are available in a multitude of languages is a fine avenue of consequent steps to redress diversities issues in health care accessibility. Longitudinal studies to reveal the impact of mHealth interventions on depression outcomes over time, as well as their cost-effectiveness in various healthcare settings, are necessary. More so, the role of social support within these apps should take precedence in future studies, looking into how the actual encouragement users have in the health area can be improved when they use the peer or family network in this application. Moreover, research also needs to highlight the ethical implications associated with data confidentiality with reference to artificial intelligence (AI) in customizing feedback, and covering users’ data responsibly and securely.

Conclusion

mHealth applications have the potential to serve as global and scalable solutions to the mental health crisis, particularly in the treatment of depression. Their integration into existing care pathways and ability to deliver customized feedback are key factors that can motivate users to engage with services and seek professional help. Furthermore, these tools offer unique advantages, such as breaking down barriers of stigma, geography, and accessibility, thus widening mental health support to marginalized communities. However, to fully harness the potential of mHealth applications, numerous difficulties must be addressed. Prioritizing sustained user engagement, addressing various cultural and linguistic requirements, and protecting users’ data privacy and security are essential objectives.

Looking forward, the development of effective digital mental health solutions requires improvements in app design, emphasizing user-centred features that enhance engagement and usability. A broader approach to accessibility must be adopted, ensuring inclusivity across demographics and regions, while a strong commitment to ethical data practices will build user trust. In conclusion, with continuous innovation and a dedicated focus on addressing these challenges, mHealth applications can significantly alter mental health care.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin for providing the necessary resources and support for this project. We also appreciate all the peers who helped with data extraction and the writing process of this manuscript, including Dr. Nurul Afiedia Roslim, Siti Maisarah Mohd Noor, Intan Anis Mohd Saupi, and Nur Kamilah Mohd Fauzy.

Funding Source

This project is being funded by the ‘Dana Penyelidikan UniSZA’ (DPU 2.0) Grant Scheme (grant number: UniSZA/2022/DPU2.0/15).

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability

This statement does not apply to this article

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not requires.

Clinical Trial Registration:

This research does not involve any clinical trials

Authors’ Contribution

Siti Nor Aqilah Mohd Noor: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft.

Umar Idris Ibrahim Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing

Shazia Jamshed: Review & Editing

Nurulumi Ahmad: Review & Editing

Aslinda Jamil: Review & Editing

Rosliza Yahaya: Review & Editing

Pei Lin Lua: Review, Visualization & Supervision

References

- World Health Organization: WHO, World Health Organization: WHO. Depressive disorder (depression). 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Le N., Belay Y. B., Le L. K. D., Pirkis J., Mihalopoulos C. Health-related quality of life in children, adolescents and young adults with self-harm or suicidality: A systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2023;57(7):952-965.

CrossRef - Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., Hatch S., Hotopf M., John A. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–892.

CrossRef - Firth J., Torous J., Nicholas J., Carney R., Pratap A., Rosenbaum S. The efficacy of smartphone‐based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):287–98.

CrossRef - Torous J., Firth J., Huckvale K., Larsen M. E., Cosco T. D., Carney R. The Emerging Imperative for a Consensus Approach Toward the Rating and Clinical Recommendation of Mental Health Apps. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2018;206(8):662–666.

CrossRef - Naslund J. A., Aschbrenner K. A., Araya R., Marsch L. A., Unützer J., Patel V. Digital technology for treating and preventing mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries: a narrative review of the literature. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):486–500.

CrossRef - Kazdin A. E., Rabbitt S. M. Novel Models for Delivering Mental Health Services and Reducing the Burdens of Mental Illness. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1(2):170–191.

CrossRef - Larsen M. E., Nicholas J., Christensen H. Quantifying App Store Dynamics: Longitudinal Tracking of Mental Health Apps. JMIR Mhealth and Uhealth. 2016;4(3):e96.

CrossRef - Hollis C., Morriss R., Martin J., Amani S., Cotton R., Denis M. Technological innovations in mental healthcare: harnessing the digital revolution. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;206(4):263–5.

CrossRef - Woody C. A., Ferrari A. J., Siskind D. J., Whiteford H. A., Harris M. G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017;219:86–92.

CrossRef - Kassim M. S. A., Ahmad N. A., Ibrahim. N., Mohd Sidik S., Idris I. B., Abdul Aziz S., Selamat Din S. H., Harith A. A., Seman Z., Mahmud M. A. F., Abd Rahims F. , Hasim @ Hisham H., Mohd Hisham M. F., Sandanasamy K. S. Depression. Putrajaya: Institute for Public Health (IPH), National Institutes of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2020. (National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019: Vol. I: NCDs – Non-Communicable Diseases: Risk Factors and other Health Problems).

- Quek J. H., Lee X. X., Yee R. L. K., Tan X. Y., Ameresekere L. S. N., Lim K. G. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Medical University Lecturers in Malaysia during COVID-19 Pandemic. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry. 2022;31(1):7–12.

CrossRef - Othman Z., Sivasubramaniam V. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Secondary School Teachers in Klang, Malaysia. International Medical Journal . 2019;26(2):71–74.

- Lizana P. A., Lera L. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Teachers during the Second COVID-19 Wave. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(10):5968.

CrossRef - Hossain M. T., Islam M. A., Jahan N., Nahar M. T., Sarker M. J. A., Rahman M. M. Mental Health Status of Teachers During the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Web-Based Study in Bangladesh. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022;13.

CrossRef - Uristemova A., Myssayev A., Meirmanov S., Migina L., Pak L., Baibussinova A. Prevalence and associated factors of depression, anxiety, and stress among academic medicine faculty in Kazakhstan: a Cross-sectional Study. PubMed. 2023;64(2):215–225.

- Santamaría M. D., Mondragon N. I., Santxo N. B., Ozamiz-Etxebarria N. Teacher stress, anxiety and depression at the beginning of the academic year during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cambridge Prisms Global Mental Health. 2021;8.

CrossRef - Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. W. The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–13.

CrossRef - BinDhim N. F., Alanazi E. M., Aljadhey H, Basyouni M. H., Kowalski S. R., Pont L. G. Does a Mobile Phone Depression-Screening App Motivate Mobile Phone Users With High Depressive Symptoms to Seek a Health Care Professional’s Help? Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2016;18(6):e156.

CrossRef - Lee R. A., Jung M. E. Evaluation of an mHealth App (DeStressify) on University Students’ Mental Health: Pilot Trial. JMIR Mental Health. 2018;5(1):e2.

CrossRef - Bakker D., Rickard N. Engagement in mobile phone app for self-monitoring of emotional wellbeing predicts changes in mental health: MoodPrism. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017;227:432–442.

CrossRef - Cheng P. G. F., Ramos R. M., Bitsch J. Á., Jonas S. M., Ix T., See P. L. Q. Psychologist in a Pocket: Lexicon Development and Content Validation of a Mobile-Based App for Depression Screening. JMIR Mhealth and Uhealth. 2016;4(3):e88.

CrossRef - Weber S., Lorenz C., Hemmings N. Improving Stress and Positive Mental Health at Work via an App-Based Intervention: A Large-Scale Multi-Center Randomized Control Trial. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10.

CrossRef - Seo J. M., Kim S. J., Na H., Kim J. H., Lee H. Effectiveness of a Mobile Application for Postpartum Depression Self-Management: Evidence from a Randomised Controlled Trial in South Korea. 2022;10(11):2185.

CrossRef - Wilhelm S., Bernstein E. E., Bentley K. H., Snorrason I., Hoeppner S. S., Klare D. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Efficacy of a Smartphone App–Led Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression Under Therapist Supervision: Open Trial. JMIR Mental Health. 2024;11:e53998.

CrossRef - Kenny R., Dooley B., Fitzgerald A. Developing mental health mobile apps: Exploring adolescents’ perspectives. Health Informatics Journal. 2014;22(2):265–275.

CrossRef - Schlosser D. A., Campellone T. R., Truong B., Etter K., Vergani S., Komaiko K. Efficacy of PRIME, a Mobile App Intervention Designed to Improve Motivation in Young People With Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2018;44(5):1010–1020.

CrossRef - Titov N., Dear B. F., Ali S., Zou J. B., Lorian C. N., Johnston L. Clinical and Cost-Effectiveness of Therapist-Guided Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Older Adults With Symptoms of Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavior Therapy. 2014;46(2):193–205.

CrossRef - Torous J, Nicholas J., Larsen M. E., Firth J., Christensen H. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: evidence, theory and improvements. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2018;21(3):116–119.

CrossRef - Phillips E. A., Gordeev V. S., Schreyögg J. Effectiveness of occupational e-mental health interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment & Health. 2019;45(6):560–576.

CrossRef - Depp C. A., Ceglowski J., Wang V. C., Yaghouti F., Mausbach B. T., Thompson W. K. Augmenting psychoeducation with a mobile intervention for bipolar disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;174:23–30.

CrossRef - Schroder H. S., Yalch M. M., Dawood S., Callahan C. P., Donnellan M. B., Moser J. S. Growth mindset of anxiety buffers the link between stressful life events and psychological distress and coping strategies. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;110:23–26.

CrossRef