Ravina Yadav1 , Ruchi Jakhmola Mani1

, Ruchi Jakhmola Mani1 , Arun Kumar2

, Arun Kumar2 , Saif Ahmad3

, Saif Ahmad3 and Deepshikha Pande Katare1*

and Deepshikha Pande Katare1*

1Proteomics and Translational Research Lab, Centre for Medical Biotechnology, Amity Institute of Biotechnology, Amity University, Noida. India.

2Department of Pharmacology, Amity Institute of Pharmacy, Amity University, Gurugram, Haryana, India.

3Department of Translational Neuroscience, Barrow Neurological Institute 350 West Thomas Road Phoenix, Arizona.

Corresponding Author E-mail: dpkatare@amity.edu

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/2990

Abstract

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) is a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Several epidemiological studies have reported a pathological association between AD and T2DM and have declared AD as a comorbidity of T2DM making T2DM a major risk factor for AD. Impaired insulin signaling elevates the risk for AD development and this can result in neurodegeneration via Aβ formation or increased inflammation in response to intraneural β amyloid. Insulin resistance, impaired glucose, carbohydrate and protein metabolism, and mitochondrial dysfunction are some characteristics common to both AD and T2DM. These features appear much before the clinical examination of both neurodegenerative diseases. It has now become extremely crucial to know the events that appear in the prodromal phases of these neurodegenerative disorders that elevate neurodegeneration risk. This has given rise to the idea that medications designed to treat T2DM may also help to alter the pathophysiology of AD and maintain cognitive function. This review highlights the recent and past evidence that correlates AD and T2DM, focusing on the shared pathogenic processes, and then evaluates the numerous medications given at clinical stages for assessing their potential activity in AD. Few molecular processes and their associated genes, altered protein metabolism (IAPP, Fyn/ERK/S6), altered carbohydrate metabolism (GLUT1, GLUT3, GLUT4), Impaired Acetylcholine (Ach) Synthesis (ACHE, ChAT), altered cholesterol metabolism (APOE4) were some of the biological reasons which made T2DM drugs useful for AD at the molecular level. Additionally, an in-silico strategy explores and evaluates the efficiency of T2DM medications like metformin, insulin, thiazolidinediones, etc. for AD treatment. The gene receptors for these drugs in the human system were predicted to understand the molecular pathways followed by these receptors which are common in AD pathology.

Keywords

Alzheimer’s Disease; Comorbidity, Drug Repurposing; Dementia; Neurodegeneration; Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Yadav R, Mani R. J, Kumar A, Ahmad S, Katare D. P. Comprehending the Rationale for Repurposing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Medicines for Alzheimer's Disease Patients Via Gene Networks Studies and its Associated Molecular Pathways. Biomed Pharmacol J 2024;17(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Yadav R, Mani R. J, Kumar A, Ahmad S, Katare D. P. Comprehending the Rationale for Repurposing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Medicines for Alzheimer's Disease Patients Via Gene Networks Studies and its Associated Molecular Pathways. Biomed Pharmacol J 2024;17(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/4fT1c3q |

Introduction

T2DM is a chronic metabolic disorder and global health concern remarked by hyperglycemia and insulin resistance 1. According to the latest IDF (International Diabetic Federation) reports there are 537 million adults of age 20-79 having diabetes in the year 2021 and expected to rise to 783 million by the year 2045. Furthermore, around 240 million individuals are still undiagnosed for Diabetic conditions 2. T2DM comprises approximately 90% of all diabetic cases 3. T2DM is insulin resistance associated with dysfunctional beta cells 4. Initially, the insulin level increases in compensation to maintain plasma glucose level, and then with the progression of the disease the β cells change and glucose homeostasis is dysregulated leading to hyperglycemia 5. Various risk factors for the disease include a sedentary lifestyle, improper calorie intake, increased obesity, and aging 6-8. All this has quadrupled the incidence of T2DM in the last 20 years. T2DM prevalence has been increasing exponentially, and an increased prevalence rate has been seen in developing nations and countries undergoing “modernization” or Westernization.9

T2DM can cause multiorgan complications and turn into other types of comorbidities like cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases, cancer, and dementia 10. Of all cases, 60% of affected individuals develop dementia in the later stages of their life. Several epidemiological studies have reported a pathological association between AD and T2DM. 11. New studies delineate a direct association between and sugar imbalance. Different studies like MRI and PET showcase impaired glucose as well as energy metabolism 12. Amyloidogenisis is a common characteristic in T2DM as well as AD. The presence of amyloidogenic peptide in the islets of Langerhans within the pancreas is a characteristic feature of T2DM, likewise, beta-amyloid plaque depositions are detected in the AD affected patients 13, 14. Alzheimer’s disease caused by diabetes mellitus induces neurodegeneration and cognitive dysfunction. A variety of histopathological evidence has shown that amyloid beta protein aggregation and hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins can be caused due to T2DM. This encapsulates the evidence that patients with T2DM are more vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease 15.

These diseases need to be monitored and managed in the early (prediabetic) stage of the disease. We are in dire need of medications that can tackle both T2DM and AD because unless T2DM is lowered we cannot lower the rising population of AD. Though there have been several drugs available for the treatment of these diseases (T2DM and AD) but fail to provide permanent cure or relief and come with multiple side effects. Also, the country’s medical healthcare system gets disturbed due to the high treatment cost, and this calls for the identification of alternative medicines for the disease for addressing this global concern.

The complexity and heterogeneity of AD have been connected to various molecular and genetic factors. The exploration of complementary approaches based on repurposing already-approved medications to treat AD has been encouraged by the sluggish pace and rising failure rate of conventional drug discovery 16. The notion of drug repurposing was initially proposed in 2004. Drug repurposing utilizes the currently available medications for disease and devises new strategies for reusing it in another disease 17. This approach has a lot of advantages over synthesizing drugs from scratch, making it a feasible and advanced approach. It involves the use of drugs in market whose patents have expired or drugs that have been withdrawn due to safety reasons and the ones which failed to show the desired safety and effectiveness in drug clinical trials. Drug repurposing is welcomed by various pharmaceutic industries due to its economic and time- saving attributes as it skips all the costly and time taking stages. This method is more advantageous than conventional approaches as it is practical, feasible and advanced. In this article, we have tried to summarize the possible connecting links between both the diseases and reported several repurposed drugs as probable therapeutics for AD. This review recapitulates and also offers information on novel potential targets for AD research.

Evidence linking T2DM AND AD

A few of the evidences validating the dementia of AD type as a comorbidity of T2DM are described below.

Preclinical studies

If T2DM shares pathological features with AD, then some crossover may be expected among both pathologies in their animal models. Though it remained undetermined to how much extent the animal models of AD showcase the evidence of metabolic changes similar to T2D, various recent studies have elucidated (a) neuropathology of AD type in T2D animal models and (b) elevated AD-type neuropathologies in rat AD models which follows experimental induction of metabolic variations of T2D like via dietary manipulations. For example, various neuronal changes have been exhibited by the T2DM rodent model BBZDR/Wor which were consistent with the pathology of AD which includes dystrophic neurites, neuronal loss, decreased insulin and IGF-1 receptor expression, tau hyperphosphorylation and increased β-amyloid (Aβ) levels 18. The OLETF model of rat 19 and db/db model of the mouse too showed Tau Hyperphosphorylation 20. There was a 9-fold elevation in the dystrophic neurites. The models provided us with useful tools for unraveling the mechanistic relationship between T2DM and AD. One major limitation of the model was that various underlying mechanisms like the role of hypercholesterolemia and caveolin signaling remained unexplored. Cognitive dysfunction and Tau hyperphosphorylation 21 are observed in Wistar rats induced with diabetes via streptozotocin (STZ). STZ is a toxin causing β-cell impairment in pancreatic cells 22. Various studies have shown that impaired signaling of insulin is due to STZ which results in lowered expression of IDE (insulin degrading enzyme) in the brain along with increased Aβ plaques and elevated tau phosphorylation 23. IDE is an important target for insulin signaling which gets elevated by the PI3K-AKT insulin pathway and forms a negative feedback mechanism 24. Hence, defective signaling of insulin might lead to lowered IDE levels because of decreased AKT activation. As IDE has also been demonstrated as a remarkable contributor for degradation of Aβ 25,26, any deprivation in the levels of IDE would cause reduced clearance of Aβ with subsequent increase in Aβ aggregation in the brain. Induction of IR in Tg2576 transgenic mice affected with AD via high fat diet leads to elevated accumulation of Aβ with lowered IDE 27. By this model, this can be hypothesized that insulin resistance might be an important underlying mechanism that is responsible for the elevated risk of AD pathology. APP/PS1 mice were given drinking water supplemented with sucrose. It exhibited increased levels of insulin, glucose intolerance, behavioral deficits and Aβ deposition 28. Thus, these evaluations via experimental paradigms linked T2DM-like metabolic variations promote neuropathologies of AD-type.

Clinical Studies

The epidemiological studies have been verified by different neuroimaging studies (MRI and PET) to monitor the brain structural alterations in AD and T2DM affected individuals and the data showed a remarkable overlap in the vulnerable regions of bran in both the pathologies.AD generally associates with brain atrophies that starts to begin in entorhinal cortex and transentorhinal cortex at an early stage and initiates its cascade in remaining neo-cortical areas 29.Several neuroimaging studies have shown that the widely emerged neurodegeneration pattern of AD in the neocortical and limbic areas that closely correlates with cognitive dysfunctions as well as behavioral patterns exhibited by AD patients .The early signs of AD pathology were found to appear in cholinergic cells at basal forebrain 30 in the NbM(nucleus basalis of Meynert) and this was revealed by a MRI studies of people affected with AD and MCI(Mild Cognitive Impairment). Moran et al.,2013 conducted a study on 350 T2DM affected indivuals with 363 controls and performed MRI scans for assessing their cognitive abilities and to find out the differential regions of brain atrophies. They found out that affected T2DM individuals had more cerebral infarction with decreased volumes of hippocampus, white matter and gray matter as compared to the unaffected diabetic individuals. Also, in T2DM patients there was a more prominent loss of gray matter in the in anterior, medial frontal, medial temporal, and cingulated lobe- the most affected regions in AD too. Moreover, the T2DM patients also showed visual spatial skills impairments. 31,32. One more study was conducted by Roberts et al.,2014 where he examined 1,437 old, aged people without dementia for knowing the T2DM association with cognitive abilities and imaging biomarkers and found that hippocampal and whole brain volumes have been reduced in midlife depicting cognitive decline in the later stages of diabetes 33. One more research was done by Wennberg et al.,2016 where 233 individuals with normal cognition were tested for blood glucose at fasting and then their MRIs were done for the cortical measurements 34. By this study they were able to predict that elevated blood glucose associates with decreased thickness of vulnerable regions of AD. Therefore, after all the observations it was concluded that brain atrophies in T2DM patients were similar to those seen in preclinical AD.

Processes linking AD and T2DM

The proposed biological processes linking T2DM, and AD are described below:

Insulin Signalling

Insulin has a vital role in controlling the release of neurotransmitters at the synapse that participate in activation of signalling pathways responsible for cognition and learning. Novel research showcases that altered insulin signalling can be involved in AD pathogenesis. Post-mortem studies on brain demonstrate that expression of insulin is inversely related to the progression of AD 35. Varied research has shown that ADDLs (amyloid beta derived diffusible ligands) act as neurotoxins and disrupt signalling at the synapses which in turn makes the cell resistant to insulin and thus, reduce the synaptic plasticity, potentiating the loss of synapse and eventually lead to the formation of reactive oxygen species resulting into oxidative damage and the formation of hyperphosphorylated tau of AD type 36,37. AD and T2DM also share certain signs of oxidative stress with AGEs (advanced glycation end products) [Figure 1]. T2DM patients tend to have a higher risk for AD development because of accumulation of AGEs in brains of AD 38. T2DM – a chronic metabolic disorder causes prolonged stress and inflammation leading to disrupted insulin signalling and impaired responsiveness 39. Many studies have demonstrated the link between neurodegeneration by Aβ formation to the mechanisms participating in T2DM in IR 40,41.In normal physiological conditions insulin binds to its receptor and starts the intrinsic activity of tyrosine kinase which further activates and phosphorylates IRS-1( insulin receptor substrate) at tyrosine position and affect downstream effector proteins like AKT/PI3K,PKβ for the metabolic functioning42 .In T2DM , faulty signalling of TNF α activates JNK(a stress kinase) which phosphorylate IRS-1 at the serine position further blocking all the downstream signalling of insulin therefore causing IR. Aβ formation also aberrantly activates TNF α , JNK and inhibition of IRS-1 at hippocampus43,44. Also, elevated level of phosphorylated IRS1 at serine position and activated JNK have been reported in the post-mortem reports of AD brains.

|

Figure 1: Association between Insulin Signalling and Alzheimer’s Disease |

Amylin receptor also acts as a common receptor for AD and T2DM. In AD, where insoluble aggregates form in the brain, amyloidogenic peptide i.e. Aβ plays a pivotal role, and in T2DM, amylin forms aggregate in the pancreas. Aβ and amylin have some common properties that can be useful for the treatment of AD and T2DM 45. Furthermore, insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) is an enzyme participates in the catalysis of Aβ clearance from brain. Its affinity for insulin is extremely high and because of this, Aβ degradation gets inhibited 46. Tau hyperphosphorylation gets affected due to defected insulin leading to formation of NFT (neurofibrillary tangles) 47. Aβ accumulation occurs due to competitive inhibition of insulin for IDE which leads to hyperinsulinemic condition and IDE deficiency. The production of IDE declines with age and the substrate level increases that lowers the insulin affinity for its receptor in-vitro. Additionally, ADDLs are also involved in causing insulin resistance (IR) in brains of AD patients. These are oligomers that are similar to prions in size and morphology. These are involved in lowering the level of insulin in brain of AD patients 39. They are more toxic than Aβ because of their diffusion rate. ADDLs works by disrupting the mechanism of binding of insulin to receptors by binding itself at the synapse changing the configuration and cause dysfunction. Due to the altered configuration at synapse, now binding of insulin is halted, further causing the damage in signal transduction causing insulin resistance. ADDLs are also involved in potentiating synaptic loss, oxidative damage and hyperphosphorylation 48. ADDLs affect the neuronal receptor signalling of insulin, cause diabetes in response to insulin resistance in brains of AD patients.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria are known as powerhouse of cell which has a very crucial role in production of ROS/RNS (reactive oxygen species /reactive nitrogen species) production. Whenever there is any dysfunction in mitochondria, oxidative imbalance occurs, and ATP production efficiency decreases that leads to elevated ROS production as in T2DM and AD. ROS production may be because of various enzymatic reactions that turns molecular oxygen to hydrogen peroxide and superoxide ions. It has been proposed that Aβ acts directly to disrupt the function of mitochondria and induces free radical production and causes neuronal damage in AD patients 49.Further, increased levels of AGEs (Advanced Glycation End-Products)/Oxidation and oxidative stress is also a common link between AD and T2DM. AGEs are the results of Maillard reaction which synthesize unstable and heterogeneous compounds by the reaction of reducing sugars to protein amino group by dehydration, rearrangement, and condensation reactions 50,51. AGE is known to cause oxidative stress by combining with free radicals and lead to cellular injuries 52,53. AGE production can elevate the risk of having AD for diabetic patients as these play an internal role in modifying Aβ plaques and tangles. The accumulation of AGEs in both T2DM and AD is due to existence of reactive sugars and phosphates, for example fructose and lead to altered cell functions, hypoglycemia and oxidative stress 54.

Systemic Inflammation

Over past few years human behaviour and lifestyle changes have greatly impacted the obesity and metabolic syndrome rates that widely contributes to T2DM. Adipokines serve to influence the mechanistic link between IR, obesity, and various inflammatory disorders 55. Macrophages and visceral fat secrete adipokines that causes lipid toxicity ultimately leading to oxidative stress, disruption of blood-brain barrier and formation of Aβ plaques (AD) 56. These adipokines include proteins like IL-1 (interleukin -1), IL6 (interleukin-1), TNFα (tumour-necrosis factor α), monocyte chemo attractant protein 1 and CRP (C Reactive protein) serving as inflammatory markers. IL6, TNF, INS, IL1B, AKT1, VEGFA, IL10, TP53, PTGS2, TLR4 are also some of the inflammatory markers common to both T2DM and AD57.

|

Figure 2: Schematic representation of series of events/processes linking T2DM and AD. |

They also function as modulators of lipid and glucose metabolism. Adipotoxicity leads to imbalance and down regulation of action of insulin on its targets, promoting inflammatory responses and cause IR and apoptotic pancreatic β cells 58. Distinct factors like JNK and Kβ-kinase inhibitor also down regulate signalling pathway of insulin and causes death of pancreatic beta- cells. This further leads to hyperglycaemia – a major characteristic feature of T2DM.

GSK3 (glycogen synthase kinase- 3) [Figure 2] has been demonstrated to be participating in pathogenesis of both AD and T2DM 59. It has been shown to be overexpressed in T2DM and its altered activity has been shown in AD too where it regulates the phosphorylation of tau and Aβ production in brain.

BACE – It is a protease which participates in cleaving APP and aids in development of AD 60. It gets expressed in β-cells of pancreas where its regulation is induced by AGEs and their receptors (RAGES) by formation of ROS through NF-Kβ pathway 61.

PLATLETS– These also represent link between AD and T2DM.AD occurs by protein misfolding with Aβ. This protein misfolding induces platelet aggregation via Ib α mediated aggregation, agglutination and CD636 62.CD636 levels of plasma are also shown to be increased in T2DM 63.

APOE (£4) -This gene plays an important role in lipid processing. Dyslipidaemia is a characteristic feature of diabetes with insulin and glucose impairment. It’s also referred to as susceptibility gene in AD having a positive correlation 64. Its prevalence varies from 5% in heterozygotes to 50 to 90% in homozygotes. The £4 isoform of APOE gene has elevated Aβ deposition. ABCA1 (a cholesterol transporter) also influence the lipid binding of APOE. In some cases, heavy deposition of Aβ occurs due to poor lipidation or deficient APOE whereas it’s over expression too is dangerous because it clears Aβ plaques beyond the appropriate level 65. Brains of AD patients and pancreas and vasculature of T2DM patients both share the pathological alterations so therefore T2DM with APOE £4 allele is more susceptible to get AD and even greater risk when provided exogenous insulin.

Table 1: Genes and pathways involved in common processes linking T2DM and AD.

|

Pathways |

Genes and pathways involved |

Summary |

|

Amyloid deposition and hyperphosphorylation in Tau |

APP, PSEN1, PSEN4 |

The presence of tau protein and β-amyloid in the pancreas is a characteristic feature for T2DM and their presence in brain indicates AD. |

|

Insulin signaling |

IRS1, IGF1, PTPN111, P85, P110, PDK1, PIP3, PTEN, PDE3B, FOXO, GSK3B, mTORC2, PI3K-Akt |

T2DM is remarked by IR or defective insulin signaling and is a very common co-morbidity and a risk factor for AD. |

|

Mitochondrial dysfunction |

APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 APOE, BACE 1, GCDH, LONP1, NOS3, JAK/STAT |

Whenever there is any dysfunction in mitochondria, oxidative imbalance occurs, and ATP production efficiency decreases that leads to elevated ROS production as in T2DM and AD. |

|

Alerted carbohydrate metabolism |

GLUT1, GLUT3, GLUT4 |

Any impairment in astrocytes can affect the survival of neurons and induce pathology like memory loss, depression and |

|

Altered protein metabolism |

IAPP, Fyn/ERK/S6 |

Oxidative alterations in proteins can lead to structural changes that can result in functional impairment contributing to mild cognitive impairment and memory loss. |

|

Systemic inflammation |

GSK3B, BACE1, APOE |

These have been shown to be overexpresssed in T2DM and its altered activity has been shown in AD too where it regulates the phosphorylation of tau and Aβ production in brain. |

|

Impaired Acetylcholine (Ach) Synthesis |

ACHE, Chat |

Lowered levels of insulin can cause AD through a decrease in Ach synthesis. |

|

Altered cholesterol metabolism |

APOE£4 |

APOE£4 plays a vital role in cholesterol hypothesis. |

|

Oxidative stress |

AGE, MDA,4-HNE, 8-OHdG, and OSI |

AGE cause oxidative stress by combining with free radicals ultimately leading to cellular injuries. AGE production can increase the risk of AD for diabetic patients. These play an internal role in modifying AβO plaques and tangles. |

|

Others |

RAGEs, LRP-1, LRP-6 |

Play an important role as a progression factor exacerbating the inflammatory and immune pathways that lead to cellular dysfunctions and may facilitate AD and T2DM interaction. |

pathological alterations so therefore T2DM with APOE £4 allele is more susceptible to get AD and even greater risk when provided exogenous insulin.

Impaired Acetylcholine (Ach) Synthesis

Multiple studies demonstrate the link between IR and abnormal Ach production 66,67. Acetylcholine transferase is involved in Ach synthesis. This enzyme is present in insulin as well as IGF-1 receptor neurons. The expression of ChAT (Acetylcholine transferase) increases with the increase in stimulation in Insulin or IGF-1. Therefore, the co-localization of ChAT in Insulin and IGF-1receptor neurons is decreased in AD patients. Decreased level of insulin and IR lowers ACH levels in body which links T2DM and AD. 68

Impaired Carbohydrate Metabolism

Altered Glucose Metabolism

Glucose is used as a source of energy for proper functioning of human body and its regulation involves a well- known coordinating role of different organs like liver, brain, and pancreas and any dysregulation in them can lead to development of various metabolic disorders. Brain has different transporters for glucose movement, GLUT-1 present in Astrocytes and endothelial cells and GLUT-3 present in neurons. Glucose crosses the blood brain barrier and enters brain via GLUT-1 and taken up by the cells for energy purposes and remaining glucose is converted to lactate. Astrocytes are involved in transport of lactate to brain by its conversion from glucose. Lactate plays a key role in neuronal metabolism like synapse and dendrite formation and gene expression in memory. Hyperglycaemia induces various changes in free radical production, glucose level in blood and neuronal apoptosis 69. Any impairment in astrocytes can affect the survival of neurons and induce pathology like memory loss, depression. Both hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia could be dangerous 70. In both T2DM and AD, age counts as a very important factor and brain at old age gets more prone to cellular damages due to excess glucose and this gives a possible reason for cognitive decline in diabetic patients 71.Thus the brain compromises due to the constant aging and hyperglycaemic condition and this very well describes the reason for T2DM patient’s brain showing patterns of cognitive impairment and cortical atrophies similar to the one that have been observed in AD preclinical stages 72,thus, if there is any impairment in the enzymes of Astrocytes that degrade glycogen, can influence the neuronal survival and it leads to formation of Aβ plaques and ultimately leads to cognitive decline and memory loss.

Altered Fructose Metabolism

Fructose –an isomer of glucose residing in two different forms in aqueous solvents. Due to its reactive open chemical structure, it has been used for baking products in the food industry. Intake of high fructose can induce protein degeneration directly as well as indirectly by elevating the glycated protein formation. Absorption of glucose occurs in small intestine that adapt to variations intake of fructose. The molecule of fructose is taken by enterocytes and transportation occurs via GLUT-5 73. Fructose is marked by high hepatic metabolism which is linked to low fructokinase activity. Fructose bypasses the energy gateway of phosphofructose kinase and gets converted to Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and pyruvate and enters the glycolytic pathway. These molecules form the backbone for triglycerides and glucose formation. These will eventually elevate the plasma glucose and stimulate insulin secretion by β -cells of pancreas and causes IR if the metabolic insulin becomes chronic and lead to high HP, endothelial dysfunction and T2DM 74. Fructose metabolism in cerebrum can play a key role in initiating AD pathway. Fructose lays a very important role by activating a survival pathway that protects the animals from starving by decreasing the energy in cells that associate it with degradation of adenosine monophosphate to uric acid. This lowered energy or energy fall from metabolism of fructose initiates foraging and intake of food by decreasing the function of mitochondria, IR and induces glycolysis. Over activation of fructose metabolism system can lead to obesity, diabetes, and AD too.75

Provision of sugar as liquid form induces more cognitive impairment as compared to the one taken in solid or for diets that are high in fats, and this occurs independently. Intake of sugars in the form of soft drinks causes cognitive dysfunction too. In FHS (Framingham Heart Study), juices and soft drinks intake is well associated to reduction(dose-dependent) in volume of hippocampus and total brain with deteriorated episodic memory 76. T2DM is also linked to the high sugar or high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) intake 77. However, there is some experimental evidences too that links this condition with endogenous production of fructose 78. Patients of T2DM with poor glycemic control also tend to have worse memory 79.

Impaired Protein Metabolism

Oxidative damage by proteins partially explains a wide variety of metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders like T2DM and AD respectively 80. T2DM is not only remarked by increased level of glucose and lipid level in blood but show a protein metabolic dysfunction also, which is mainly due to deficient secretion of insulin 81. Insulin promotes synthesis of protein and inhibition of protein decomposition 82 and elevated insulin and IGF1 levels in serum promote metabolism of proteins. Compared with a normal group, catabolism of protein was ameliorated in diabetic models whereas the syntheses of protein and mRNA expression of IGF1, IR as well as IGF1R were significantly decreased 83. Also, the branched-chain amino acids like leucine, isoleucine and other related metabolites have been associated positively with IR. The accumulation of protein is a common characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases. These proteins aggregate in different compartments from the ones they localize. Studies from last decade have predicted that the UPR (unfolded protein response) markers like p-inositol-requiring enzyme (IRE), phosphorylated- (p-) protein kinase double-stranded RNA-dependent (PKR)-like the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) kinase (PERK), eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (p-eIF2α) and binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP) were increased in tissues of AD patients 84-86. The widely studied markers in the UPR are PERK-eIF2α axis that facilitate production of Aβ and regulate synaptic plasticity 87. UPR and ER stress markers were found to be increased in the inflamed islets of T2DM mice 88,89. In addition, UPR or ER markers are also elevated in AD pathology 90. It is demonstrated that Aβ formation occurs upstream of tau hyperphosphorylation in the pathological cascade of AD 91-94. In AD phosphorylation of Tau is mainly at threonine and serine position. Generally, hyperphosphorylated tau gets detached from the microtubules in the axon and passes through the initial segment of axon, which acts as a diffusion barrier for physiologically phosphorylated tau and this process is controlled by Aβ 95-97. Recently, it has been elucidated that Aβ can trigger over expression of tau directly via translation of protein Fyn/ERK/S6 signaling pathway activation in somato-dendritic domain 97 Many evidences also suggest the role of Aβ, IAPP (islet amyloid polypeptide) and Tau in promoting T2DM and exacerbating neurodegeneration further. 98

Autophagy Dysfunction

Intracellular accumulation in misfolded proteins is an important characteristic of many neurodegenerative diseases 99. Autophagy is a mechanism of removal of protein aggregates from neurons. Oxidative stress is caused by IR in T2DM further causing ROS production and damage to various intracellular organelles like mitochondria and ER 100. This induces downstream pathways of clearance and removal of the misfolded proteins present in lumen of ER and damaged organelles 101. However, in continuous long stress cases inefficient autophagy and accumulation of autophagosomes increases. This leads to an impaired tolerance to glucose, decreased pancreatic β cells, lowered blood insulin 102. This leads to a progressive building up of toxic aggregates of proteins Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles triggering AD pathogenesis [Fig 3]. This autophagic impairment can also be a major risk factor to T2DM development leading to a vicious cycle where T2DM induces hyperphosphorylation of tau and promote autophagosomal accumulation in neurons. This abnormal clearance of autophage then promotes neurodegeneration leading to AD pathogenesis and opens new doors for developing pro-autophagy drugs.

Role of Gut Microbiota

There has been a lot of growing interest in the field of research to know the importance of gut microbial flora in human health and diseases. There have been a lot of technological advances that have initiated the interest in knowing the relationship between human health and gut microbiota. It includes around hundred trillion of microorganisms with thousands of different bacteria crucially participating in pathophysiological process 103. It is now well understood that the gut microbial flora can affect the central nervous system that leads to brain function modulation 104,105. Recently multiple studies have used germ-free organisms that have been exposed to antibiotics, probiotic and pathogenic bacteria have illustrated that gut microbiota composition can influence the post-natal development of brain 106. It plays a pivotal role in pain responses and changing behavior too 104-105. There are numerous evidences that supports the close interaction of the gut microbiota with immune system. It can also be postulated that gut microbiota influences the functions of central nervous system via immune cells. Immune cells like T- cells and microglia release cytokines that play crucial part in brain development and neuronal plasticity 107-109. Gut microbiota has a crucial impact in different neurological and psychiatric disorders via the influence of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune system interaction. Any imbalance in gastrointestinal environment (Dysbiosis) contributes to developing AD and T2DM. There are numerous nerves that end in intestinal mucosa and regulate the function of intestine and interact with brain via vagus nerve and transmit signals to GIS tract and vice versa. Dysbiosis breaks intestinal permeability leading to release of inflammatory cytokines in blood as well as brain. Mediators too can play this role via vagus nerve 110. Pathogens such as Salmonella produce H2S in the gut by degrading Sulphur containing amino acids. Elevated H2S level inhibits COX activity and shifts the metabolism to glycolysis and lead to upregulated lactate and decrease in ATP production 111. It has also been reported that increased H2S level results in decreased consumption of mitochondrial oxygen and all this leads to upregulation of proinflammatory mediators (IL6) causing AD and T2DM 112.

Hormonal Imbalance

Testosterone

Low testosterone or testosterone depletion in men also known as andropause leads to various symptoms that shows the vulnerability and impairment in the responsive tissues like muscle, brain, adipose tissues, and bone 113. Multiple studies have shown andropause as a crucial risk factor for the development of AD 114. Males with depleted of testosterone in brain 115 or blood 116 are at high risk to AD development. The lowering of testosterone starts even before the neuropathological or cognitive diagnosis 117 for AD which confirms it to be a defined contributing factor. Multiple growing epidemiological researches has indicated a strong link between the level of testosterone in T2DM as well as other metabolic diseases too. Various studies have illustrated a link between insulin resistance and low testosterone in males proposed the importance of lowered testosterone in insulin resistance 118. Low level of testosterone starts 10-15 years earlier before the development of any metabolic disease 119. Therefore, T2D affected men would have lowered free and total testosterone level. Testosterone therapy has proved to be efficient for treating androgen deficiency and significantly lowers the features of T2DM as well as other metabolic syndromes which includes cholesterol, adiposity and insulin resistance and improved the glycemic control 120. Also, the androgen deprivation therapy used for prostate cancer treatment has indicated that depletion of testosterone can elevate the prevalence and incidence of T2D 121 and metabolic syndrome 122. Various available researches have also demonstrated that T2DM significantly lowers the level of testosterone in males and conversely low level of testosterone can increase the risk of T2DM 123.

Other Factors

Among the other possible mechanisms oxidative stress, lipoprotein receptors and vascular risk factors are also involved in AD and T2DM relationship. Vascular risk factors comprise of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and cerebrovascular diseases. Various researches have showcased that the combining effect of these vascular factors advocates AD and its related malignancies development 124,125. Defects in blood-brain barrier and brain vasculature have been seen in patients affected with AD 126 proposing the importance of vascular factors in AD pathogenesis. Lipoprotein receptors as well as lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1) are some elements participating in T2DM and AD that help in clearance of Aβ from brain and liver 127,128. LRP-1 is involved in storage of fatty acids and intracellular cholesterol 129 and LRP-6 plays a very important role in regulating glucose homeostasis and body weight 130. Pathways that regulate LRP-1 improve Aβ-induced learning as well as memory deficits in rats 131. RAGE’s (the receptor for advanced glycation end products) have been found to be an important ligand for the Aβ plaques 132,133 and are found to be involved in neurotoxicity of Aβ fibrils in microglia and neurons 134. Also, RAGE modulates the Aβ accumulation and transport across the blood-brain barrier 135. RAGEs are upregulated in AD as well as T2DM 136 therefore, they play an important role as a progression factor exacerbating the inflammatory and immune pathways that lead to cellular dysfunctions 137 and may facilitate AD and T2D interaction.

Methodology

Literature Mining

Exhaustive literature review was done following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines 138. Various DBs were explored including PubMed, PMC, and Science Direct. Few of the keywords used for data mining were “Type 2 Diabetes and AD”, “Neurodegeneration in T2DM”, “Impaired insulin signaling”, “cognitive decline in T2DM”, “amyloid beta”, “neuroinflammation”, “drug repurposing” etc. Figure 1 demonstrates the plan followed for the text mining. The results were recorded and cited accordingly.

1985 records were screened in total that were obtained from the above-mentioned databases which were screened with the use of EndNote 20 first and then the duplicates 55 were eliminated. Abstracts and titles of the rest of the 1930 records were then screened further based on their target relevance. 390 records have been found appropriate and sought for their full reports and lastly 161 studies were selected that fell in the eligibility criteria [Figure 3].

Criteria of Inclusion and Exclusion

Systemic reviews were included and selected that usually had AD progression or AD or cognitive decline or improvement as a result. The studies and results of experiments were selected and considered when they showed significant data for mechanisms among T2DM as well as AD. Authentic studies that elucidated effects of the drugs available already and their relationship with the receptors serving as a potential target for the treatment of AD were included. Research studies lacking clarity and rigor were not included. And articles written only in English were considered [Figure 3].

|

Figure 3: Systematic literature review as guided by PRISMA 2020 guidelines. |

Results and Discussion

Repurposing of T2DM drugs for AD patients

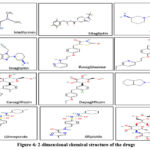

Drug Development is time-taking and a bit expensive process. Repurposing the current medications for therapeutics is an appealing strategy that expedites the development of drug at lower experimental costs 139. Chemical, biological and clinal field data is building up exponentially and has enough potential for accelerating and providing new insights for drug development. Creating analytical tools to integrate this heterogenous and complicated data to a testable hypothesis and useful insights is a challenging and opportunistic task, therefore the goal of computational pharmacology is to understand better and predict the mechanism of action of drugs in biological system. This can further enhance therapeutic use, prevent the negative side effects, and direct in selecting and developing better treatment. As all these drugs are approved already via regulatory agency such as FDA (the Food and Drug Administration) and their availability in bulk makes them economical and time and resource saving as compared to the conventional method where went through various preclinical trials and toxicity testing for ensuring safety 140. Drug repurposing for AD treatment appears to be a workable approach as strategies used conventionally for AD were proved unsuccessful from last 10 years. Figure 4 shows the drugs developed for T2DM that can be repurposed for the treatment of AD. With the approach of drug repurposing and focus on disease biology, several anti-diabetic drugs have been recognized that showed significant effects on AD pathogenesis. Also, it was noticed that the current drugs used for AD have their targets in the brain only, but the identified repurposed drugs target different receptors present in different organs of the body like the liver, pancreas, colon, bone marrow, etc. This thus widens the range of target receptors available for AD research presently.

Extensive Literature search was performed for knowing repurposed drug of AD that are recently being utilized and have shown an association with the receptors that may serve as significant target for the treatment. Initially, the drugs and their 2-D structures [Figure 4] have been procured form the PubChem Database 141. The aim was to determine the biological pathway used by the target protein classes of the repurposed medicines and whether it overlapped with any currently known AD-related pathways. Swiss Target Prediction 142 which is an online too offered by the ExPASy (Expert Protein Analysis System) 143 was used for the target receptor prediction and results are summarized in Table 2. This table compared the already available receptors with the one that have been predicted computationally through Swiss target Prediction. This will help us in designing of drugs for the pathologies by targeting the specific biological pathways.

Table 2: Gene receptors predicted for Type 2 diabetes drugs and their already known receptors.

|

Drug |

SMILES (From PubChem Database) |

Known Receptor |

Predicted Receptors (computationally) |

|

Metformin |

CN(C)C(=N) N=C(N)N |

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 β (GSK 3 -β) |

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator Histamine H4 receptor D-amino-acid oxidase Histamine H3 receptor Xanthine dehydrogenase Dihydrofolate reductase (by homology) Integrin alpha-V/beta-3 Coagulation factor IX Neuronal acetylcholine receptor; alpha4/beta2 S-100 protein beta chain Beta-hexosaminidase subunit alpha Beta-N-acetyl-D-hexosaminidase-A/B Solute carrier family 22 member 1 (by homology) |

|

Sitagliptin |

C1CN2C(=NN=C2C |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) |

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV Dipeptidyl peptidase VIII Fibroblast activation protein alpha Dipeptidyl peptidase IX Dipeptidyl peptidase II Glycine transporter 1 Chymase CaM kinase II C-C chemokine receptor type 2 Histone-arginine methyltransferase CARM1 (by homology) |

|

Alogliptin |

CN1C(=O) C=C |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) |

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV Dipeptidyl peptidase VIII Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M2 (by homology) Neurokinin 1 receptor (by homology) Delta opioid receptor Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase-1 Kinesin-like protein 1 Retinoid X receptor alpha Protein kinase C delta Protein kinase C alpha |

|

Linagliptin |

CC#CCN1C2=C |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) |

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M1 Dipeptidyl peptidase IV Fibroblast activation protein alpha Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 Dipeptidyl peptidase IX MAP kinase p38 alpha C-C chemokine receptor type 8 Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta Thrombin and coagulation factor X |

|

Rosiglitazone |

CN(CCOC1=CC=C |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG)

|

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma Thromboxane-A synthase Monoamine oxidase B Carbonic anhydrase II Type-1 angiotensin II receptor (by homology) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta Bile salt export pump Free fatty acid receptor 1 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase [NAD+] |

|

Pioglitazone |

CCC1=CN=C(C=C1) |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG)

|

Monoamine oxidase B Carbonic anhydrase II Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha Bile salt export pump Thromboxane-A synthase Type-1 angiotensin II receptor (by homology) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase [NAD+] Free fatty acid receptor 1 |

|

Canagliflozin |

CC1=C(C=C(C=C1) |

Sodium glucose co-transporter 2(SGLT2) |

Sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 Sodium/glucose cotransporter 1 Glucose transporter (by homology) Phosphodiesterase 5A Adenosine A1 receptor (by homology) Adenosine A2a receptor Adenosine A3 receptor Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 Adenosine kinase Coagulation factor VII/tissue factor |

|

Dapagliflozin |

CCOC1=CC=C(C=C1) |

Sodium glucose co-transporter 2(SGLT2) |

Sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 Sodium/glucose cotransporter 1 Sodium/myo-inositol cotransporter 2 Low affinity sodium-glucose cotransporter Adenosine kinase MAP kinase p38 alpha Adenosine A2a receptor (by homology) Adenosine A3 receptor Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 |

|

Gliclazide |

CC1=CC=C(C=C1) |

Sulphonylurea 1(SUR1) |

Phosphodiesterase 10A P2X purinoceptor 7 Cytochrome P450 19A1 Bromodomain-containing protein 4 Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2 Matrix metalloproteinase 9 Matrix metalloproteinase 2 Matrix metalloproteinase 14 Adenosine A2a receptor Adenosine A2b receptor |

|

Glimepiride |

CCC1=C(CN(C1=O) |

Sulphonylurea 1(SUR1) |

Proteinoid EP4 receptor Proteasome subunit beta type 9 Cannabinoid receptor 2 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 12 Tyrosine-protein kinase BRK PI3-kinase p110-delta subunit PI3-kinase p110-beta subunit PI3-kinase p110-gamma subunit PI3-kinase p110-alpha subunit Acetyl-coenzyme A transporter 1 |

|

Glipizide |

CC1=CN=C(C=N1)C |

Sulphonylurea 1(SUR1) |

Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK3 Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2 Serotonin 7 (5-HT7) receptor Serine/threonine-protein kinase mTOR Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 Prostanoid EP3 receptor Sodium channel protein type IX alpha subunit |

|

Acarbose |

CC1C(C(C(C(O1)OC2C |

Maltase-glucoamylase |

Pancreatic alpha-amylase AMY1C Lysosomal alpha-glucosidase Maltase-glucoamylase Sucrase-isomaltase Trehalase Adenosine A2a receptor (by homology) Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 Beta-glucocerebrosidase (by homology) Beta-galactosidase |

Anti-Diabetic Drugs which can be used for AD.

Insulin resistance develops when people affected with T2DM are unable to use the hormone insulin adequately 144. Insulin transports the blood glucose to cells where it is used as an energy source for the functioning of various bodily functions. Insulin resistance hampers the uptake of blood glucose in the cells which causes blood sugar levels to rise even while the cells are starving. The Rotterdam study found that people affected with diabetes mellitus are two times more likely to acquire AD, suggesting that antidiabetic medications may be helpful in treating AD 145.

Metformin

Patients affected with T2DM are given metformin which is an insulin-sensitizing medication that helps the body to effectively use insulin by overcoming insulin resistance and allowing the cells to use glucose. Metformin works by inhibiting GSK-3β enzyme present in liver which is thought to be advantageous for AD patients 146. Neuronal degeneration is caused by insulin resistance and hence by overcoming this will reduce the damage to neuronal system and improvise cognitive functioning. Figure 4 elucidates the 2-D structure for Metformin.

|

Figure 4: 2-dimensional chemical structure of the drugs |

Sitagliptin

It is an oral DPP-4 inhibitor that is effective in managing T2DM. It leads to an increase in GLP-1 and GIP and shows a strong response of insulin for glucose. The neuroprotective effects of dipeptidyl-peptidase (DPP)-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin have recently received much attention. Sitagliptin was also found to be effective in treating AD. Studies on animals demonstrated sitagliptin’s neuroprotective impact, which enhances learning. Additionally, via influencing macrophages, sitagliptin has demonstrated an anti-apoptotic action that was thought to be an anti-inflammatory drug 147. Figure 4 elucidates the 2-D chemical structure for Sitagliptin.

Alogliptin

It is an anti-diabetic drug that is significantly effective in treating AD. Alogliptin works by inhibiting DPP-4, which degrades GLP1 and GIP. Incretin activity is increased in plasma because of DPP-4 inhibition, aiding in glycemic management. Figure 4 elucidates the 2-D chemical structure for Alogliptin.

Linagliptin:

Linagliptin is another antidiabetic drug that has shown significant results in treating Alzheimer’s and is now under investigation. By blocking GSK3 activation, linagliptin improves insulin signaling and lowers tau protein hyperphosphorylation. A decline in the A42/A40 ratio was observed in a mouse study on the use of linagliptin for AD. This has led to a decrease in senile plaques formation as well as decreased deposition of NFT, improving the cognitive abilities 148. Hence, showing it to be a worthy candidate research. Figure 4 displays the 2-D structure for Linagliptin.

Rosiglitazone

PPARγ, which is present in colon adipose tissues and macrophages, is the major target of rosiglitazone. As a conventional anti-diabetic medication, it also helps in reducing neuroinflammation and aids in amyloid-beta peptide clearance in AD mouse models making it a potential therapeutic option for humans 149. The 2-D molecular structure of Rosiglitazone is shown in Figure 4.

Pioglitazone

Like Rosiglitazone, Pioglitazone also targets the Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and works by stimulating microglial cells in a specific way to reduce cytokine release, inhibit neuroinflammation, and catalyze the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides 149. The medication can be regarded as a viable treatment, despite the fact that research is still in its early phases. The 2-D molecular structure of pioglitazone is shown in Figure 4.

Canagliflozin

Canagliflozin is an SGLT-2 inhibitor that is taken to manage hyperglycemia in T2DM. Ongoing research shows activity of SGLT2 inhibitors on AChE2 enzyme (target for AD). Canagliflozin is involved in inhibition of both SGLT2 and AChE and this may be used for developing new drug for AD and T2DM 150. The 2-D molecular structure of Canagliflozin is shown in Figure 4.

Dopaglifozin

It’s a SGLT-2 inhibitor conventionally taken for treating T2DM..Recent studies elucidate its effectiveness in AD too. SGLT2 inhibitors were initially unknown in AD. According to some molecular docking studies, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition activity has been shown by various SGLT-2 inhibitors, which serves as a significant therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s. Dapagliflozin can act as inhibitor for both AChE and SGLT2. The possible effect of combined SGLT2 and AChE inhibition via single compound can be helpful in establishing novel drugs that act as antidiabetic action and anti-AD 151. The 2-D molecular structure of Dapagliflozin is shown in Figure 4.

Glimipiride

The sulfonylurea receptor, SUR1 present on the pancreatic cell membrane, which glimepiride binds to (Figure 4), stimulates insulin production by blocking the potassium ion channel. It is said to have additional pancreatic effects on glucose absorption, potentiating the release of GPI-anchored proteins, and PPARγ activation. Also, it upregulates the expression of PPAR’s target genes that include leptin and aP2 and improves the interaction of PPARγ with cofactors. PPARγ activation has been shown to lower Aβ and senile plaque levels, which enhances cognitive functions in affected AD people 152. Gliclazide and Glipizide are two more drugs having similar mode of action and act as an effective therapeutic for AD. The 2-D molecular structure of the Glimepiride, Gliclazide and Glipizide is shown in Figure 4.

|

Figure 5: Protein interaction networks of the individual drugs a) Linagliptin b) Metformin c) Glipizide d) Glimepiride e) Gliclazide |

Figure 5 shows the protein-protein interaction networks for the listed individual drugs. These networks have been extracted from a bioinformatic tool -Cytoscape. Cytoscape is a platform that is open sourced that visualizes complex networks by integrating them with attribute data. The protein targets were predicted via Swiss Target Prediction tool which belonged to different protein classes and later their biological processes were also identified (Table 3). It was seen that Metformin, Linagliptin, Canagliflozin, Liraglutide, Rosiglitazone and Pioglitazone participated in protein-kinase cascades processes through respective protein targets. The biological pathways shown by the conventional drug of T2DM are also the pathways generally affected in AD. Therefore, we can conclude that these drugs if used judiciously they can be taken for repurposing for treatment of AD.

Table 3: Biological Processes followed by the drug in Human Systems.

|

Name of drug |

Class |

P – value |

Biological processes involved |

|

Metformin |

Biguanide |

6.19E-07 0.00043 0.00043 0.00043 0.00054 0.00054 0.00071 0.00071 0.00071 0.0008 |

Signalling receptor binding Carbonate dehydratase activity Epidermal growth factor receptor binding Ion binding Nitric-oxide synthase activity Flavin adenine dinucleotide binding Integrin binding G protein-coupled amine receptor activity Tetrahydrobiopterin binding DNA replication origin binding |

|

Sitagliptin |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors |

6.24E-25

1.68E-24

3.72E-24

5.90E-24

4.87E-22

1.17E-21

1.34E-21

3.21E-21

6.89E-21

1.29E-20 |

Response to stimulus Signalling Cell communication Regulation of biological quality Cellular response to stimulus Response to organic substance Positive regulation of biological process Signal transduction Cellular response to chemical stimulus Response to chemical |

|

Alogliptin |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors |

1.49E-30 4.03E-22 1.09E-21 1.09E-21 2.10E-21 2.80E-21 4.70E-21 7.14E-21 7.14E-21 2.11E-20 |

Protein phosphorylation Cellular response to stimulus Signal transduction Intracellular signal transduction Signalling Response to stimulus Cell communication Protein metabolic process Response to oxygen-containing compound Cellular response to chemical stimulus |

|

Linagliptin |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors |

5.28E-31 1.32E-30 3.27E-26 9.29E-26 3.51E-25 1.03E-24 1.25E-24 1.58E-24 3.27E-24 8.67E-24 |

Protein autophosphorylation Protein phosphorylation Phosphorylation regulation of intracellular protein kinase cascade Response to stimulus Peptidyl-amino acid modification Signal transduction Response to chemical Protein metabolic process Regulation of cell population proliferation |

|

Rosiglitazone |

Thiazolidinedione |

5.81E-23 3.27E -02 9.03E-22 3.39E-19 4.38E-19 3.70E-18 8.80E-18 2.71E-17 7.55E-17 1.94E-16 |

Response to organic substance positive regulation of IL3-biosynthetic process Response to chemical Response to endogenous stimulus Cellular response to organic substance Cellular response to chemical stimulus regulation of intracellular protein kinase cascade Cell communication Response to stress Regulation of localization |

|

Pioglitazone |

Thiazolidinedione |

2.34E-18 4.11E-18 1.22E-17 1.57E-17 2.80E-17 5.54E-16 7.96E-16 2.06E-15 5.21E-15 1.19E-14 |

Response to oxygen-containing compound Response to organic substance positive regulation of IL-3 biosynthetic process Response to endogenous stimulus Response to chemical Cellular response to chemical stimulus Response to lipid Cellular response to endogenous stimulus Response to stimulus Regulation of biological quality |

|

Canagliflozin |

Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors |

1.32E-20 1.32E-20 1.32E-20 1.53E-20 1.91E-20 2.80E-20 3.43E-20 3.66E-20 3.92E-20 6.47E-20 |

Positive regulation of kinase activity Positive regulation of transferase activity Cellular response to chemical stimulus Regulation of transferase activity Organonitrogen compound metabolic process Response to chemical Positive regulation of cell communication Positive regulation of signalling Positive regulation of protein ser/thr kinase activity Metabolic process |

|

Dapagliflozin |

Sodium glucose co-transporter 2(SGLT2) inhibitors |

1.55E-27 6.94E-26 3.43E-23 2.94E-21 1.18E-20 1.18E-20 2.08E-20 6.68E-20 8.79E-20 9.19E-20 |

Phosphorylation Protein phosphorylation Phosphate-containing compound metabolic process Organic substance metabolic process Metabolic process Primary metabolic process Positive regulation of catalytic activity Regulation of transferase activity Cell surface receptor signaling pathway Positive regulation of protein metabolic process |

|

Gliclazide |

Sulphonylurea |

8.24E-25 1.37E-24 7.17E-24 1.29E-23 1.32E-23 1.32E-23 2.24E-23 8.56E-23 9.81E-23 9.81E-23 |

Response to organic substance Response to stimulus Cellular response to stimulus Cell communication Positive regulation of r protein metabolic process Positive regulation of protein metabolic process Signaling Signal transduction Regulation of cell communication Regulation of transferase activity |

|

Glimepiride |

Sulphonylurea |

3.82E-39 6.78E-38 1.05E-37 2.23E-36 2.22E-34 4.43E-33 1.09E-32 9.69E-32 6.14E-31 1.46E-30 |

Protein phosphorylation Phosphorylation Cellular response to organic substance Cellular response to chemical stimulus Response to organic substance Phosphate-containing compound metabolic process Intracellular signal transduction Cellular response to endogenous stimulus Response to endogenous stimulus Cellular response to oxygen-containing compound |

|

Glipizide |

Sulphonylurea |

1.96E-35 6.43E-30 1.16E-29 4.92E-29 8.69E-28 1.69E-27 2.12E-27 3.01E-27 1.04E-26 1.06E-26 |

Protein phosphorylation Cell communication Signalling Intracellular signal transduction Response to chemical Phosphate-containing compound metabolic process Cellular response to chemical stimulus Signal transduction Response to organic substance Regulation of response to stimulus |

|

Acarbose |

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors |

2.70E-14 7.48E-14 7.48E-14 3.57E-13 2.15E-10 7.17E-10 1.15E-09 2.42E-09 2.42E-09 2.88E-09 |

Response to organic substance Response to organic cyclic compound Response to chemical Response to oxygen-containing compound One-carbon metabolic process Response to organonitrogen compound Regulation of cell population proliferation Response to stimulus Cellular response to chemical stimulus Metabolic process |

Medications like Pioglitazone and Rosiglitazone participate in biosynthetic process of IL-3 that is one of the major processes studied for AD treatment. Hence it can be summarized that these medications can be repurposed with the current drugs of AD if wisely chosen. These medications also follow similar molecular and biological processes that can be seen in clinical stories of these repurposed drugs.

Side effects for the reported Repurposed Drugs

All the drugs come with

various complexities. Many side effects have been reported in AD patients

receiving T2DM drugs. Various major and minor side effects have been listed in

Table 4. Many of the side effects reported for all the drugs are very

detrimental for AD patients and therefore must be considered again prior to

going forward with them for AD treatment. Before considering any of

the medications as therapeutic target, it is important to take their toxicity

into account. This toxicity could be

harmful for AD patients due to their old age and a compromised immune system.

Table 4: Side effects of Type 2 Diabetes drugs in Alzheimer’s patients

|

Drugs |

General Side effects |

Side effects noticed in AD patients |

Citations |

|

Metformin |

Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, lactic acidosis; hypoglycemia, headache, rhinitis, chest discomfort. |

Worse cognitive performance; Vitamin B12 deficiency |

153 |

|

Sitagliptin, Alogliptin, linagliptin |

Gastrointestinal discomfort including nausea abdominal pain, diarrhea nausea and hypoglycemia |

Trembling or shaking, sweating, confusion, difficulty concentrating

|

154 |

|

Rosiglitazone, |

Liver disease, congestive heart failure, fluid retention |

Dizziness, Peripheral edema, hyperlipidemia, edema, dizziness Nasopharyngitis |

155 |

|

Pioglitazone |

Osteoporosis weight gain, edema, congestive heart failure (CHF) |

No side effect |

156 |

|

Canagliflozin, Dapagliflozin |

Elevated cholesterol, dehydration, yeast infections, kidney problems |

Genitourinary infections, euglycemic ketoacidosis |

157 |

|

Acarbose |

Diarrhea, abdominal distention, and nausea |

Intestinal side effects |

158 |

In summary, the current work displays the common links in T2DM, and AD. Various Epidemiological studies have reported pathological associations between AD and T2DM and have declared AD as a comorbidity of T2DM, thus making T2DM a major risk factor for AD. Insulin resistance, impaired glucose, carbohydrate and protein metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction have been found to be the characteristics common to both AD and T2DM. there have been many medications available for the treatment of both the disease but all these fail to provide permanent cure relief and have multiple side effects. Also, the country’s medical healthcare system gets disturbed due to the high treatment cost and this calls for identification of alternative medicines for the disease for addressing this global concern. There are many receptors common in both the disorders and hence calls for making drugs which can address both the pathologies Therefore, the exploration of repurposing already-approved medications of T2DM to treat AD has been encouraged.Drug repurposing utilizes the currently available medications for a disease and devises new strategies for reusing it in another disease.In this article we have tried to summarize the possible connecting links between both the pathologies and reported several T2DM drugs which can be repurposed as probable therapeutics for AD. This review also summarizes information on novel potential targets for AD research.

Our study confirms the feasibility of repurposed antidiabetic drugs for neurodegenerative disorders. AD is the one of the most prevalent neurological disorders in elderly people and recent studies provides detailed information of the epidemiological evidences about the relationship among T2DM and neurodegenerative disorders and mechanism of various antidiabetic drugs for treating neurodegenerative disorders. This work explores new receptors common to both the diseases based on the drugs which can be commonly used for this dual pathology. Drug repurposing is the future of pharmaceutics as it can bring novelty in its usage in a different disorder. Therefore, it should be encouraged in other diseases and more research should be done in this field.

Conclusion

In this article we have tried to summarize the common shared links between T2DM and AD which are the two most common independent metabolic malignancies. We have depicted the shared pathophysiology by elaborating the underlying mechanistic pathways. Cognitive impairment severity relies on the type of diabetes, the onset age, and other malignancies. Keeping in mind the current evidences it is very well known that hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, altered carbohydrate and protein metabolism relate to cognitive impairment and are important characteristics for T2DM. In T2DM affected people, insulin resistance causes dysregulated glucose and insulin metabolism, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation.

Various studies elucidate the feasibility of repurposed antidiabetic drugs for neurodegenerative disorders.AD is the one of the most prevalent neurological disorders in elderly people and recent studies provides detailed information of the epidemiological evidences about the relationship among T2DM and neurodegenerative disorders and mechanism of various antidiabetic drugs for treating neurodegenerative disorders. GLP-1 receptor agonists too have an important and significant neuroprotective as well as neurotrophic role by their intervention in PI3K/AKT and cAMP/PKA signaling pathway as well as regulating intracellular calcium homeostasis and inflammatory processes.

Based on all the results from the studies done, this conclusion could be made that drug repurposing can also serve as an important and novel approach for treating AD. Additionally, all these findings can also be justified further by the use of computational tools for the examination of the drug-target interactions and then the best drugs could be identified .Therefore this technique of drug repurposing could be considered as feasible and advanced approach for the drug development after working upon the certain loopholes.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Dr. Ashok K. Chauhan, Founder President, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida for providing the infrastructure and support.

Conflict of Interest

Prof. Deepshikha Pande Katare and Ravina Yadav declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

The study was not funded by any funding agency.

References

- Mirza Z, Ali A, A Kamal M, M Abuzenadah A, G Choudhary A, A Damanhouri G, A Sheikh I. Proteomics approaches to understand linkage between Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders. 2014; 13(2):213-25.

- Ogurtsova K, Guariguata L, Barengo NC, Ruiz PL, Sacre JW, Karuranga S, Sun H, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ.. IDF diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2022; 83:109118.

- Stumvoll M., Goldstein B.J., van Haeften T.W. Type 2 diabetes: Principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet. 2005; 365:1333–1346. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61032-X

- Cerf ME. Beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2013; 4:37.

- Cersosimo E, Triplitt C, Solis-Herrera C, Mandarino LJ, DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endotext [Internet]. 2018.

- Lee PG, Halter JB. The pathophysiology of hyperglycemia in older adults: clinical considerations. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(4):444-52.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 29(Suppl. 1). 2006; S43–S48pmid:16373932

- Khan MA, Hashim MJ, King JK, Govender RD, Mustafa H, Al Kaabi J..Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes–global burden of disease and forecasted trends. Journal of epidemiology and global health. 2020; 10(1):107.

- Wu Y, Ding Y, Tanaka Y, Zhang W. Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. International journal of medical sciences. 2014; 11(11):1185.

- Pradeepa R, Mohan V. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in India. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021; 69(11):2932.

- Grossmann K. Direct oral anticoagulants: a new therapy against Alzheimer’s disease?.Neural Regeneration Research. 2021; 16(8):1556.

- Ronnemaa, E., Zethelius, B., Sundelof, J., Sundstrom, J., Degerman-Gunnarsson, M., Berne, C., … Kilander, L.. Impaired insulin secretion increases the risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008; 71(14), 1065–1071.

- Stanciu GD, Bild V, Ababei DC, Rusu RN, Cobzaru A, Paduraru L, Bulea D. Link between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease due to the shared amyloid aggregation and deposition involving both neurodegenerative changes and neurovascular damages. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(6):1713.

- Haataja, L., Gurlo, T., Huang, C. J., and Butler, P. C. 2008 Islet amyloid in type 2 diabetes, and the toxic oligomer hypothesis. Endocr. Rev. 2020; 29, 303–316. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0037

- Mittal, K., & Katare, D. P. Shared links between type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2016; 10(2), S144–S149. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2016.01.021

- Padhi D, Govindaraju T. Mechanistic Insights for Drug Repurposing and the Design of Hybrid Drugs for Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2022.

- Zhu S, Bai Q, Li L, Xu T. Drug repositioning in drug discovery of T2DM and repositioning potential of antidiabetic agents. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2022.

- Li ZG, Zhang W, Sima AA. Alzheimer-like changes in rat models of spontaneous diabetes. Diabetes. 2007 Jul 1;56(7):1817-24.

- Jung HJ, Kim YJ, Eggert S, et al. Age-dependent increases in tau phosphorylation in the brains of type 2 diabetic rats correlate with a reduced expression of p62. Exp Neurol. 2013 ; 248C:441–450

- Kim B, Backus C, Oh S, et al. Increased tau phosphorylation and cleavage in mouse models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Endocrinology. 2019 ; 150:5294–52301

- Planel E, Tatebayashi Y, Miyasaka T, et al. Insulin dysfunction induces in vivo tau hyperphosphorylation through distinct mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2007; 27:13635–13648

- Biessels GJ, Kamal A, Urban IJ, et al. Water maze learning and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in streptozotocin-diabetic rats: effects of insulin treatment. Brain Res. 1998; 800:125–135

- olivalt CG, Lee CA, Beiswenger KK, et al. Defective insulin signaling pathway and increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity in the brain of diabetic mice: parallels with Alzheimer’s disease and correction by insulin. J Neurosci Res. 2008; 86:3265–3274

- Zhao L, Teter B, Morihara T, et al. Insulin-degrading enzyme as a downstream target of insulin receptor signaling cascade: implications for Alzheimer’s disease intervention. J Neurosci. 2004; 24:11120–11126

- Chesneau V, Vekrellis K, Rosner MR, Selkoe DJ. Purified recombinant insulindegrading enzyme degrades amyloid beta-protein but does not promote its oligomerization. Biochem J. 2000;351(Pt 2):509–516

- Farris W, Mansourian S, Chang Y, et al. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta0amyloid precursor protein intacellular domain in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003; 100:4162–4167.

- Ho L, Qin W, Pompl PN, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance promotes amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Faseb J. 2004; 18:902–904

- Cao D, Lu H, Lewis TL, Li L. Intake of sucrose-sweetened water induces insulin resistance and exacerbates memory deficits and amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282:36275–36282.

- Fjell, A. M., Amlien, I. K., Sneve, M. H., Grydeland, H., Tamnes, C. K., Chaplin, T. A., et al. The roots of Alzheimer’s disease: are high-expanding cortical areas preferentially targeted?. Cereb. Cortex 25, 2556–2565. 2015; doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu055

- Schmitz, T. W., Nathan Spreng, R., and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Basal forebrain degeneration precedes and predicts the cortical spread of Alzheimer’s pathology. Nat. Commun. 2016; 7:13249. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13249

- Beckett, L. A., Donohue, M. C., Wang, C., Aisen, P., Harvey, D. J., Saito, N., et al. The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative phase 2: increasing the length, breadth, and depth of our understanding. Alzheimers Dement. 2015; 11, 823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.004

- Moran, C., Beare, R., Phan, T. G., Bruce, D. G., Callisaya, M. L., Srikanth, V., et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and biomarkers of neurodegeneration. Neurology 85. 2015; 1123–1130.doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001982

- Roberts, R. O., Knopman, D. S., Przybelski, S. A., Mielke, M. M., Kantarci, K., Preboske, G. M., et al. Association of type 2 diabetes with brain atrophy and cognitive impairment. Neurology 82. 2014; 1132–1141. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000269

- Wennberg, A. M., Spira, A. P., Pettigrew, C., Soldan, A., Zipunnikov, V., Rebok, G. W., et al. Blood glucose levels and cortical thinning in cognitively normal, middle-aged adults. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016; 365, 89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.04.017

- Kroner Z. The Relationship between Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes: Type 3 Diabetes. Alternative Medicine Review. 2009 Dec 1;14(4).

- P.N. Lacor, M.C. Buniel, P.W. Furlow, A.S. Clemente, P.T. Velasco, M. Wood, K.L. Viola, W.L. Klein, Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease, J. Neurosci. 2007; 27 796–807.

- G.M. Shankar, B.L. Bloodgood, M. Townsend, D.M. Walsh, D.J. Selkoe, B.L. Sabatini, Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway, J. Neurosci. 2007; 27 2866–2875.

- Viola KL, Velasco PT, Klein WL. Why Alzheimer’s is a disease of memory: the attack on synapses by A beta oligomers (ADDLs).J Nutr Health A^íii^ 2008;I2:51S-57S.

- Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol 2011; 29:415–45

- Craft S. Alzheimer disease: insulin resistance and AD: extending the translational path. Nat Rev Neurol 2012; 8:360

- Bomfim TR, Forny-Germano L, Sathler LB, Brito-Moreira J, Houzel JC, Decker H, et al. An anti-diabetes agent protects the mouse S30 F.G. De Felice et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 10 (2014) S26–S32 brain from defective insulin signaling caused by Alzheimer’s diseaseassociated Ab oligomers. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:1339–53.

- White MF. Insulin signaling in health and disease. Science 2003; 302:1710–1

- Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Gorgun CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, et al. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature 2002; 420:333–6

- Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol 2011; 29:415–45

- Fu, W., Patel, A., & Jhamandas, J. H. Amylin Receptor: A Common Pathophysiological Target in Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes Mellitus. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 5. 2013; doi:10.3389/fnagi.2013.00042

- Craft S, Stennis G. Insulin and neurodegenerative disease: shared and specific mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2004; 3(3):169–78.

- Hong M, Lee Y. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 regulate tau phosphorylation in cultured human neurons. J Biol Chem. 1997; 272(31): 19547–53

- De Feiice FG. Wu D, Lambert MP, et al. Alzheimers 30. disease-type neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation induced by A beta oligoniers. Netirobiol Aging. 2008; 29:1334-1347

- M. Manczak, T.S. Anekonda, E. Henson, B.S. Park, J. Quinn, P.H. Reddy.Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006; 15, pp. 1437-1449

- Yamagishi S, Ueda S, Okuda S. Food-derived advanced glycation end products (AGEs): a novel therapeutic target for various disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2007; 13: 2832–6.

- Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S. Possible involvement of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008; 14: 973–8.

- Sato T, Shimogaito N, Wu X, et al. Toxic advanced glycation end products (TAGE) theory in Alzheimer’s disease. AmJ Alzheimers Dis Other Dcnien. 2006;21:197-208.

- Pasquier F, Boulogne A, Leys D, Fontaine P. Diahetcs mellirus and dementia. Diahetes Metah. 2006; 32:403- 414

- Munch G, Schinzel R, Loske C, Wong A, Durany N, Li JJ, Vlassara H, Smith MA, Perry G, Riederer P. Alzheimer’s disease – synergistic effects of glucose deficit, oxidative stress and advanced glycation endproducts. J Neural Transm. 1998; 105: 439–61

- Antuna-Puente, B., Feve, B., Fellahi, S., & Bastard, J.-P. Adipokines: The missing link between insulin resistance and obesity. Diabetes & Metabolism. 2008; 34(1), 2–11. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2007.09.004

- Adams Jr., J. Alzheimers Disease, Ceramide, Visfatin and NAD. CNS & Neurological Disorders – Drug Targets. 2008; 7(6), 492–498. doi:10.2174/187152708787122969

- Yuan X, Wang H, Zhang F, Zhang M, Wang Q, Wang J. The common genes involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes and their implication for drug repositioning. Neuropharmacology. 2023 Feb 1;223:109327.

- Eldor, R., & Raz, I. Lipotoxicity versus adipotoxicity—The deleterious effects of adipose tissue on beta cells in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.2006; 74(2), S3–S8.

- Jolivalt CG, Lee CA, Beiswenger KK, et al. Defective insulin signaling pathway and increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity in the brain of diabetic mice: parallels with Alzheimer’s disease and correction by insulin. J Neurosci Res 2008; 86: 3265-74.

- Ahmed RR, Holler CJ, Webb RL, Li F, Beckett TL, Murphy MP. BACE1 and BACE2 enzymatic activities in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 2010; 112: 1045-53