Tahani H Ibrahim1* , Sara Almutiri1, Manahil Alharbi1

, Sara Almutiri1, Manahil Alharbi1 , Dana Alotaibi1

, Dana Alotaibi1 , Mehboob Ali2

, Mehboob Ali2 , Waleed Hamza3

, Waleed Hamza3  and Mohamed Zaki4

and Mohamed Zaki4

1Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, Qassim University, Buraidah KSA.

2Prince Sultan cardiac center, King Fahad Specialist Hospital, Buraydah, QHC, MOH,KSA

3King Saud Hospital, Unaizah, QHC, MOH,KSA.

4Al-Bukayria General Hospital, QHC, MOH,KSA.

Corresponding Author E-mail: tahani-ibrahim@hotmail.com

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/2756

Abstract

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) which known as subcategory of coronary heart disease is considered a major cause of death. In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of ACS is 8.2%. Early recognition of risk factors (RFs) associated with ACS is essential to prevent its progression. Therefore, the goals of this study is to estimate the prevalence of cardiovascular RFs among ACS patients and to appraise its association with the development of ACS. This retrospective multi-center cross-sectional study involved 170 patients admitted to Prince Sultan cardiac center, King Saud Hospital, and Bukayriyah General Hospital in Al Qassim, KSA. The participants categorized into three groups UA, NSTEMI, and STEMI. Patients with stable angina or previous MI were excluded from the study. 73.5% were males and 26.5% were females with a mean age of 58.2 ± 11.9. The distribution of ACS subtypes was 51.2%, 27.6%, and 21.2% for STEMI, NSTEMI and UA, respectively. The most common RFs were diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (66% each), and dyslipidemia (58%). The prevalence of RFs among STEMI group was 65.6% active smokers, 54.5% dyslipidemia, and 52.2% ischemic heart disease (IHD). On the other hand, in NSTEMI group hypertension and DM were nearly the same (32% & 30% respectively), however family history of IHD was 42.9%. UA revealed a strong association with IHD and family history of IHD (30.4%, 28.6%, respectively).To conclude, most of ACS patients presented with STEMI followed by NSTEMI and the least with UA. Among the cardiovascular risk factors, HTN, DM, and dyslipidemia, were presented in more than half of the patients which strongly suggests an association with developing ACS.

Keywords

Acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI; Risk factors; STEM; Unstable angina

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Ibrahim T. H, Almutiri S, Alharbi M, Alotaibi D, Ali M, Hamza W, Zaki M. Relationship between Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Development of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Biomed Pharmacol J 2023;16(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Ibrahim T. H, Almutiri S, Alharbi M, Alotaibi D, Ali M, Hamza W, Zaki M. Relationship between Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Development of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Biomed Pharmacol J 2023;16(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/3Lr3kls |

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a subcategory of ischemic heart disease, is considered a major cause of mortality.1 In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of ACS among the population is 8.2%, most of them diagnosed with unstable angina (19.2%).2 ACS comprise a group of disorders that arise from acute myocardial ischemia.3 These disorders include UA, NSTEMI , and STEMI.3-5 Risk factors of coronary artery disease include non-Modifiable RFs which comprise family history, race, age, and gender; modifiable like type2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, Obesity, and metabolic syndrome.6.7 Prevention and early detection of risk factors diminished the rate of morbidity and mortality associated with CAD. In spite of the fact that Saudi Arabia is known for its ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity which may contribute to ACS, there is a lack of studies about ACS. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the prevalence of cardiovascular RFs among patients admitted to Prince Sultan cardiac center, King Saud Hospital, and Bukayriyah General Hospital and to determine their association with different ACS subtypes.

Research Design and Methods:

Study design

A retrospective multi-center cross-sectional study was conducted on 170 patients admitted to Prince Sultan cardiac center, King Saud Hospital, and Bukayriyah General Hospital in Al Qassim, KSA. The ACS patients were classified into UA, NSTEMI, and STEMI. Patients with stable angina or previous MI were excluded from the study. Participants’ data was retrieved from patients’ medical records in a predesigned data collection form focusing on demographic characteristics and RFs such as family history, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Al- Qassim Regional Ethical Committee.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was fed to IBM SPSS software version 22 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL). All statistical analysis was done using two-tailed tests. Descriptive analysis performed for all variables including patients’ socio-demographic data, weight, height, and nationality. Different risk factors of ACS were also displayed such as diabetes, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, and IHD history. Crosstabulation was used to evaluate the distribution of ACS subtypes by reported risk factors and patients’ data. Pearson chi-square test and exact probability test for small frequency distributions were used to assess the associations. P-value less than 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

A total of 170 patients were included. Patients’ ages ranged from 28 to 87 years with a mean age of 58.2 ± 11.9 years old. 125 patients (73.5%) were males and 45 (26.5%) were females. As for nationality, 131 (77%) patients were Saudi. Considering body mass index, 36 (21.2%) patients had normal weights, 82 (48.2%) were overweight, and 52 (30.6%) were obese (Table 1).

Table 1: Bio-demographic data of study participants

|

Data |

N |

% |

|

Age in years |

|

|

|

< 50 |

43 |

25.3 |

|

50-59 |

52 |

30.6 |

|

60-69 |

45 |

26.5 |

|

70+ |

30 |

17.6 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

Male |

125 |

73.5 |

|

Female |

45 |

26.5 |

|

Nationality |

|

|

|

Saudi |

131 |

77.1 |

|

Non-Saudi |

39 |

22.9 |

|

Body mass index |

|

|

|

Normal |

36 |

21.2 |

|

Overweight |

82 |

48.2 |

|

Obese |

52 |

30.6 |

A total of 87 patients (51.2%) had STEMI, 47 (27.6%) had NSTEMI, and 36 (21.2%) complained of unstable angina (Figure1).

|

Figure 1: Distribution of acute coronary syndromes subtypes among study participants. |

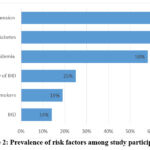

Figure 2 demonstrates the risk factors prevalence among patients with ACS. The most-reported risk factors were diabetes mellitus, and hypertension (66% each), followed by dyslipidemia (58%), family history of IHD (25%), smoking (19%), and IHD (14%).

|

Figure 2: Prevalence of risk factors among study participants |

Table2 shows a significant difference regarding smoking status by patient age as all patients aged 70 years or more were non-smokers compared to 41.9% of the age group less than 50 years were active smokers (P=.001). All other risk factors were insignificantly associated with patients’ age but all of them were higher among old aged patients (70 years or more) except for IHD.

Table 2: Association between risk factors and different age groups

|

Risk factors |

Age in years |

p-value |

|||

|

< 50 |

50-59 |

60-69 |

70+ |

||

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

||

|

Active smoker |

.001 |

||||

|

Yes |

18 (41.9) |

10 (19.2) |

4 (9.1) |

0 (0) |

|

|

No |

25 (58.1) |

42 (80.8) |

40 (90.9) |

30 (100) |

|

|

Hypertension |

.818 |

||||

|

Yes |

26 (60.5) |

35 (67.3) |

30 (68.2) |

21 (70) |

|

|

No |

17 (39.5) |

17 (32.7) |

14 (31.8) |

9 (30) |

|

|

Diabetes |

.221 |

||||

|

Yes |

27 (62.8) |

30 (57.7) |

33 (73.3) |

23 (76.7) |

|

|

No |

16 (37.2) |

22 (42.3) |

12 (26.7) |

7 (23.3) |

|

|

Dyslipidaemia |

.980 |

||||

|

Yes |

24 (55.8) |

31 (59.6) |

26 (57.8) |

18 (60) |

|

|

No |

19 (44.2) |

21 (40.4) |

19 (42.2) |

12 (40) |

|

|

Family history of IHDa |

.526$ |

||||

|

Yes |

1 (11.1) |

2 (28.6) |

1 (20) |

3 (42.9) |

|

|

No |

8 (88.9) |

5 (71.4) |

4 (80) |

4 (57.1) |

|

|

IHDa |

.368$ |

||||

|

Yes |

7 (33.3) |

2 (11.8) |

3 (21.4) |

2 (14.3) |

|

|

No |

14 (66.7) |

15 (88.2) |

11 (78.6) |

12 (85.7) |

|

P: Pearson X2 test $: Exact probability test N: number

P-value < 0.05 considered significant

a, IHD: ischemic heart disease

Table 3 shows the distribution of different ACS subtypes by age, gender, and BMI. 65.1% of young aged patients (< 50 years) had STEMI while 40% of old aged patients (70+) had NSTEMI with no statistical significance (P=.188). A total of 52.8% of males had STEMI versus 46.7% of female patients (P=.375). Also, 61.1% of patients with normal body weight had STEMI compared to 52.4% of overweight and 42.3% of obese patients (P=.229).

Table 3: Distribution of acute coronary syndrome subtypes by age, gender, BMI

|

Personal data |

Type |

p-value |

||

|

NSTEMIb |

STEMIa |

Unstable angina |

||

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

||

|

Age in years |

.188 |

|||

|

< 50 |

10 (23.3) |

28 (65.1) |

5 (11.6) |

|

|

50-59 |

11 (21.2) |

27 (51.9) |

14 (26.9) |

|

|

60-69 |

14 (31.1) |

21 (46.7) |

10 (22.2) |

|

|

70+ |

12 (40.0) |

11 (36.7) |

7 (23.3) |

|

|

Gender |

.375 |

|||

|

Male |

31 (24.8) |

66 (52.8) |

28 (22.4) |

|

|

Female |

16 (35.6) |

21 (46.7) |

8 (17.8) |

|

|

Body mass index |

.229 |

|||

|

Normal |

10 (27.8) |

22 (61.1) |

4 (11.1) |

|

|

Overweight |

23 (28.0) |

43 (52.4) |

16 (19.5) |

|

|

Obese |

14 (26.9) |

22 (42.3) |

16 (30.8) |

|

Regarding Association between different ACS subtypes and cardiovascular risk factors (Table4). The exact 65.6% of active smokers had STEMI compared to 48.2% of non-smokers with no statistical significance (P=0.190). Also, 50% of patients with hypertension complained of STEMI versus 54.4% of non- hypertensive (P=0.158). STEMI was diagnosed among 52.6% of non-diabetic patients compared to 50.4% of diabetic patients (P=0.542). Additionally, 54.5% of patients with dyslipidemia complained of STEMI versus 46.5% of others without (P=0.308). Family history of IHD was associated with developing NSTEMI (42.9%) compared to 28.6% of patients without (P=0.550). A total of 52.2% of patients with IHD developed STEMI compared to 51% of others without (0.351).

Table 4: Association between different acute coronary syndrome subtypes and cardiovascular risk factors.

|

Risk factors |

Type |

p-value |

|||||

|

NSTEMIb |

STEMIa |

Unstable angina |

|||||

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

|||||

|

Active smoker |

.190 |

||||||

|

Yes |

7 (21.9) |

21 (65.6) |

4 (12.5) |

||||

|

No |

40 (29.2) |

66 (48.2) |

31 (22.6) |

||||

|

Hypertension |

.158 |

||||||

|

Yes |

36 (32.1) |

56 (50.0) |

20 (17.9) |

||||

|

No |

11 (19.3) |

31 (54.4) |

15 (26.3) |

||||

|

Diabetes |

.542 |

||||||

|

Yes |

34 (30.1) |

57 (50.4) |

22 (19.5) |

||||

|

No |

13 (22.8) |

30 (52.6) |

14 (24.6) |

||||

|

Dyslipidaemia |

.308 |

||||||

|

Yes |

28 (28.3) |

54 (54.5) |

17 (17.2) |

||||

|

No |

19 (26.8) |

33 (46.5) |

19 (26.8) |

||||

|

Family history of IHDc |

.550$ |

||||||

|

Yes |

3 (42.9) |

2 (28.6) |

2 (28.6) |

||||

|

No |

6 (28.6) |

11 (52.4) |

4 (19) |

||||

|

IHDc |

.351 |

||||||

|

Yes |

4 (17.4) |

12 (52.2) |

7 (30.4) |

||||

|

No |

43 (29.3) |

75 (51) |

29 (19.7) |

||||

Discussion

Out of the total number of patients included in the current study, 51.2% of them presented with STEMI, while 27.6% and 21.2% of them presented with NSTEMI and UA respectively. The distribution of ACS subtypes was as expected according to previous studies which reported that STEMI was the most common presentation in ACS patients, followed by NSTEMI, and UA. 8,9 STARS-1 Program (The first survey of the Saudi Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry Program ) reported that among 2233 patients with ACS, 65.9% of them had STEMI and 34.1% had NSTEMI. They attributed this distribution to the relatively young age of ACS appearance in their sample.10 However, in contrast to their findings, the current study revealed that younger patients have the lowest risk factors.

According to the current study, 73.5% of the patients were males, while 26.5% were females. These findings align with various studies that have indicated a higher prevalence of all risk factors among males.11,12,13,14 Despite the fact that more than half of male patients present with STEMI, the occurrence of NSTEMI is lower compared to female patients, as confirmed by multiple studies.15,16 However, the gender association with ACS progression remains uncertain.

Most of the ACS patients in the current study were 50 years old or older (74.7%), and among all age groups, STEMI was higher in the younger age. In agreement with this finding, earlier studies documented inverse relationship between STEMI and patients’ age.9,17

Considering body mass index four publications examined CVD prevalence rates according to obesity status and discovered a favorable correlation between obesity and elevated CVD prevalence.18, 19, 20, 21.

Based on the patients’ BMI data our results showed that obese and overweight patients were at higher risk for ACS compared to normal-weight patients and most of them presented with STEMI. And our claim was supported by a study performed locally that demonstrated that even a mild elevation in a patient’s BMI was considered as a risk factor for developing ACS.22, 23, 24. Interestingly our results showed that overweight patients were at higher risk of ACS (48.2%) compared to obese patients (30.6%). However, unexpectedly normal weight patients were the most diagnosed with STEMI (61.1%) compared to both overweight and obese patients. In our study, the BMI relationship with UA has a predictable pattern which exhibits that with each increase in BMI the percentage of UA cases increases.

We generally recognize risk factors through epidemiological findings.25 The high prevalence of the cardiovascular disease is due to specific lifestyle characteristics and related risk factors. Many cardiovascular risk factors contribute to ACS. These factors are classified into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.26 In Saudi Arabia according to the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology study (PURE-Saudi) which focus on the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease risk factors demonstrated that the most common risk factor was physical inactivity (69.4%) followed by obesity 34.4%, unhealthy eating 32.1%, dyslipidemia (32.1%), hypertension (30.3%), diabetes (25.1%) and low percentage of the population were active smokers (12.2%).27

In the present study, a significant percentage of ACS patients had DM (66%) and HTN (66%) as risk factors, followed by dyslipidemia with a percentage of 58%. However, we observed a low percentage of active smokers among the patients. This could be due to the fact that the average age of our sample is 58 years old, with the majority of patients being above 40 years old. Previous studies conducted in Saudi Arabia have shown that the younger age group (40 years old or younger) has the highest percentage of smokers, reaching 84.8%.28

The main concern of our study was to find the association between cardiovascular risk factors and ACS subtypes, and we focus on six main risk factors. Starting with smoking which is considered a crucial risk factor.29 Most of the smokers’ patients in our sample were at higher risk for developing STEMI (65.6%) compared to non-smokers. Out of studies that have supported this association, one study showed that smoking raises the risk of developing ACS even in those who smoke less than 5 cigarettes per day.30, 31

HTN along with DM appears to be higher in NSTEMI compared with other ACS subtypes. These results were consistent with some previous studies. An epidemiological study conducted on patients with NSTEMI shows that two-thirds of the population was suffering from chronic HTN. 32

According to the Saudi Project for Assessment of Coronary Events (SPACE) study HTN was the second most risk factor found in CAD patients in Saudi Arabia with a percent of 48%.8 Hypertension prevalence increases with age.33 Seeing that most of our patients were older, it is no strange that HTN was one of the most risk factors along with DM according to our results.

In Saudi Arabia according to the latest edition of “IDF Diabetes Atlas” the prevalence of adults with diabetes currently is 18.7%. And Saudi Arabia classified as the seventh-highest country with new cases of diabetes type 1.34 In general, men with diabetes were twice more susceptible to CVD than nondiabetic . Among diabetic women, the prevalence of CVD was about three times that those who were nondiabetic .35 Dyslipidemia also appeared to be a critical risk factor for ACS according to our findings and previous studies.33,36 By comparing dyslipidemia presence with ACS subtypes it showed an increased presentation of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. These outcomes were compatible with earlier studies.36, 37 In one study that was conducted on ACS patients with a mean age of 59 years old which is similar to what we got (58 years) shows that most of them presented mostly with STEMI (61%) followed by NSTEMI (25.7%) and with a lower percentage of UA (13.3%).37Finally Based on our results, having an IHD or a family history of IHD was associated with a higher percentage of UA but particularly IHD as a risk factor was associated with a higher occurrence of STEMI unlike the family history of IHD where most patients presented with NSTEMI. 24

Conclusion

To conclude, out of 170 patients with ACS included in the study most of them were males, at the age of 50 years old or more, with elevated BMI. Furthermore, 51.21% of them presented with STEMI followed by 27.6% with NSTEMI and 21.2% with UA. Among the cardiovascular risk factors, HTN, DM, and dyslipidemia were presented in more than half of the patients which strongly suggests an association with developing ACS.

References

- Barstow C, Rice M, McDivitt JD. Acute coronary syndrome: Diagnostic evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(3):170–7.

- Mohammed S, Mohammed A, Alharbi S, Algorinees R, Alghuraymil AA, Alsaif M. Incidence of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS). In: EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARC.

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, De C, Ganiats TG, Dr H. AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):e344-426.

- Singh A, Museedi AS, Grossman SA. Acute Coronary Syndrome. In: FL: StatPearls Publishing. 2021.

- Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA. JAMA patient page. Acute coronary syndrome. JAMA [Internet]. 2015;314(18):1990. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12743

CrossRef - Maleki A, Ghanavati R, Montazeri M, Forughi S, Nabatchi B. Prevalence of coronary artery disease and the associated risk factors in the adult population of Borujerd city, Iran. J Tehran Heart Cent [Internet]. 2019;14(1):1–5. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.18502/jthc.v14i1.648

CrossRef - Nowbar AN, Gitto M, Howard JP, Francis DP, Al-Lamee R. Mortality from Ischemic heart disease: Analysis of data from the World Health Organization and coronary artery disease risk factors from NCD risk factor collaboration. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes [Internet]. 2019;12(6):e005375. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005375

CrossRef - AlHabib KF, Hersi A, AlFaleh H, Kurdi M, Arafah M, Youssef M, et al. The Saudi Project for Assessment of Coronary Events (SPACE) registry: Design and results of a phase I pilot study. Can J Cardiol [Internet]. 2009;25(7):e255–8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70513-6

CrossRef - Al Bugami S, Alhosyni F, Alamry B, Alyami A, Abadi M, Ahmed A, et al. Acute coronary syndrome among young patients in Saudi Arabia Single center study. J cardiol curr res [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Feb 12];12(12). Available from: https://medcraveonline.com/medcrave.org/ index.php/JCCR/article/view/7754

CrossRef - Alhabib KF, Kinsara AJ, Alghamdi S, Al-Murayeh M, Hussein GA, AlSaif S, et al. The first survey of the Saudi Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry Program: Main results and long-term outcomes (STARS-1 Program). PLoS One [Internet]. 2019;14(5):e0216551. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216551

CrossRef - Jafary MH, Samad A, Ishaq M, Jawaid SA, Vohra EA. Profile of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2007;23(4):485–9.

- Balakrishnan VK, Chopra A, Muralidharan TR, Thanikachalam S. Clinical profile of acute coronary syndrome among young adults. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Res. 2018;4(1):52–9.

- Cheema FM, Cheema HM, Akram Z. Identification of risk factors of acute coronary syndrome in young patients between 18-40 years of age at a teaching hospital. Pak J Med Sci Q [Internet]. 2020;36(4):821–4. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.4.2302

CrossRef - Styczkiewicz K, Styczkiewicz M, Myćka M, Mędrek S, Kondraciuk T, Czerkies-Bieleń A, et al. Clinical presentation and treatment of acute coronary syndrome as well as 1- year survival of patients hospitalized due to cancer: A 7-year experience of a nonacademic center: A 7-year experience of a nonacademic center. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2020;99(5):e18972. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018972

CrossRef - Mariani J, Macchia A, De Abreu M, Gonzalez Villa Monte G, Tajer C. Multivessel versus single vessel angioplasty in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: A systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016;11(2):e0148756. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148756

CrossRef - Page RL 2nd, Ghushchyan V, Van Den Bos J, Gray TJ, Hoetzer GL, Bhandary D, et al. The cost of inpatient death associated with acute coronary syndrome. Vasc Health Risk Manag [Internet]. 2016;12:13–21. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S94026

CrossRef - Ahmed E, Alhabib KF, El-Menyar A, Asaad N, Sulaiman K, Hersi A, et al. Age and clinical outcomes in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes. J Cardiovasc Dis Res [Internet]. 2013;4(2):134–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcdr.2012.08.005

CrossRef - Bhatti GK, Bhadada SK, Vijayvergiya R, Mastana SS, Bhatti JS. Metabolic syndrome and risk of major coronary events among the urban diabetic patients: North Indian Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease Study-NIDCVD-2. J Diabetes Complications [Internet]. 2016;30(1):72–8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.jdiacomp.2015.07.008

CrossRef - Tamba SM, Ewane ME, Bonny A, Muisi CN, Ellong NE, Mvogo A, et al. Micro and macrovascular complications of diabetes mellitus in Cameroon: risk factors and effect of diabetic check-up-a monocentric observational study. Pan African Medical Journal. 2013;15(1).

CrossRef - Wentworth JM, Fourlanos S, Colman PG. Body mass index correlates with ischemic heart disease and albuminuria in long-standing type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract [Internet]. 2012;97(1):57–62. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2012.02.012

CrossRef - Glogner S, Rosengren A, Olsson M, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Svensson AM, Lind M. The association between BMI and hospitalization for heart failure in 83 021 persons with Type 2 diabetes: a population-based study from the Swedish National Diabetes Registry. Diabetic medicine. 2014;31:586–94.

CrossRef - Al-Nozha MM, Arafah MR, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Maatouq MA, Khan NB, Khalil MZ, et al. Coronary artery disease in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(9):1165–71.

- Foussas S. Obesity and acute coronary syndromes. Hellenic J Cardiol [Internet]. 2016;57(1):63–5. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1109-9666(16)30023-9

CrossRef - Basoor A, Cotant JF, Randhawa G, Janjua M, Badshah A, DeGregorio M, et al. High prevalence of obesity in young patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart Hosp J [Internet]. 2011 Summer;9(1):E37-40. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.15420/ahhj.2011.9.1.37

CrossRef - Epidemiology is a science of high importance. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2018;9(1):1703. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04243-3

CrossRef - Acute coronary syndrome: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Pharm J [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 12]; Available from: https://pharmaceutical- journal.com/article/ld/acute-coronary-syndrome-risk-factors-diagnosis-and-trea

- Alhabib KF, Batais MA, Almigbal TH, Alshamiri MQ, Altaradi H, Rangarajan S, et al. Demographic, behavioral, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Saudi population: results from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology study (PURE-Saudi). BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020;20(1):1213. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09298-w

CrossRef - AlMutairi H, Aftan A, Alqarni L, Amer F, Alhajji M, AlSaihati R, et al. Smoking and related diseases in Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Dev Ctries [Internet]. 2019;586–91. Available from: https://www.ejmanager.com/mnstemps/51/51- 1548005162.pdf?t=1644434513

CrossRef - Yagi H, Komukai K, Hashimoto K, Kawai M, Ogawa T, Anzawa R, et al. Difference in risk factors between acute coronary syndrome and stable angina pectoris in the Japanese: smoking as a crucial risk factor of acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiol [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2022 Feb 12];55(3):345–53. Available from: https://www.journal-of-cardiology.com/article/S0914-5087(10)00006-7/fulltext

CrossRef - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US), Office on Smoking and Health (US). Cardiovascular diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

- Neaton JD, Kuller LH, Wentworth D, Borhani NO. Total and cardiovascular mortality in relation to cigarette smoking, serum cholesterol concentration, and diastolic blood pressure among black and white males followed up for five years. Am Heart J [Internet]. 1984;108(3):759–70. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002- 8703(84)90669-0

CrossRef - Picariello C, Lazzeri C, Attanà P, Chiostri M, Gensini GF, Valente S. The impact of hypertension on patients with acute coronary syndromes. Int J Hypertens [Internet]. 2011;2011:563657. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/563657

CrossRef - Levy D, Wilson PWF, Anderson KM, Castelli WP. Stratifying the patient at risk from coronary disease: New insights from the framingham heart study. Am Heart J [Internet]. 1990;119(3):712–7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0002- 8703(05)80050-x

CrossRef - IDF diabetes atlas [Internet]. Diabetesatlas.org. [cited 2022 Feb 12]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org

- Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: the Framingham study. Circulation [Internet]. 1979;59(1):8–13. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.59.1.8

CrossRef - Gonzalez-Pacheco H, Vallejo M, Altamirano-Castillo A, Vargas-Barron J, Pina-Reyna Y, Sanchez-Tapia P, et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors and lipid profiles in patients with acute coronary syndrome and significant coronary disease. Ther Clin Risk Manag [Internet]. 2014;815. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.s67945

CrossRef - Dhungana SP, Mahato AK, Ghimire R, Shreewastav RK. Prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with acute coronary syndrome admitted at tertiary care hospital in Nepal: A descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc [Internet]. 2020;58(224):204–8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.31729/jnma.4765

CrossRef