Kiran Chawla1* , Ajay Kumar2

, Ajay Kumar2 , Asha Hegde3

, Asha Hegde3 and Arun Kumar Govindakarnavar4

and Arun Kumar Govindakarnavar4

1Department of Microbiology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal. Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India

2Department of Microbiology, Manipal TATA Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India

3Department of Paediatrics, Melaka Manipal Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India

4Manipal Centre for Virus Research, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India

Corresponding Author E-mail: kiran.chawla@manipal.edu

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/2405

Abstract

Objective: Aetiological diagnosis can significantly impact the clinical management and outcome of acute lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) in children. There is a paucity of data on etiological agents of acute LRTI among children in Karnataka, especially in Udupi district. Present study provides an insight into the pathogens associated with acute LRTI among children in Udupi district of south coastal Karnataka. Methods: A cross sectional study was performed at a rural hospital in south coastal Karnataka, A total of 50 children clinically diagnosed for acute LRTI and admitted in paediatric ward were enrolled for the study. Nasopharyngeal/throat swab specimens were collected, and nucleic acid was extracted, and Multiplex real-time PCR was performed for detection of bacterial and viral aetiology. Results: S. pneumoniae was detected in 16% (8/50), followed by Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) 14% (7/50), H. influenzae 8 % (4/50) and M. pneumoniae 2% (1/50). Mixed infection was detected in 28% (14/50) of children. S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae was the most prevalent co-infection and was detected in 10% (5/50) followed by H. Influenzae and RSV (4%, 2/50) co-infection. Conclusion: S. pneumoniae and RSV were the most predominant bacterial and viral pathogens respectively associated with LRTIs among paediatric population in present study. Further we found very high number of cases with mixed infections which signifies the urgent need of much elaborate studies for elucidating the clinical significance of these infections as well as for better understanding of epidemiology of LRTI among children in this region.

Keywords

Haemophilus influenzae; Influenza Virus A; Respiratory Syncytial Virus; Streptococcus pneumoniae

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Chawla K, Kumar A, Hegde A, Govindakarnavar A. K. A Pilot Study on Aetiology of Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infections Among Children Hospitalized of Respiratory Illness at a Rural Hospital in South Coastal Karnataka. Biomed Pharmacol J 2022;15(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Chawla K, Kumar A, Hegde A, Govindakarnavar A. K. A Pilot Study on Aetiology of Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infections Among Children Hospitalized of Respiratory Illness at a Rural Hospital in South Coastal Karnataka. Biomed Pharmacol J 2022;15(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/3Mb6oAj |

Introduction

The burden of respiratory tract infections among the paediatric population in India is growing faster day by day due to polluted environment, poor lifestyle, and inadequate care. Respiratory tract infections account for the highest number of deaths among children every year in majority of developing countries like India. Pneumonia accounts for 17% of all deaths among the children below 5 years of age in India1. Further 30-40 % of hospital admissions in developing countries are due to lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI)2. Thus, LRTI remains one of the major healthcare issues worldwide. Due to involvement of a wide range of pathogens, lack of specific clinical presentation, and inability of conventional diagnostic methods to provide timely and efficient diagnosis; establishing the aetiology of LRTI always remains a challenge. Recently developed molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and real time PCR offer great promise as future diagnostics for respiratory tract infection providing rapid identification of pathogens with high sensitivity and specificity. It also permits identification of more than one pathogen in the same respiratory specimen that has previously been difficult to culture3. Aetiological diagnosis can significantly impact the clinical management and outcome of acute LRTI in children. There is a paucity of data on etiological agents of acute LRTI among children in Karnataka, especially in Udupi district. Present study provides an insight into the pathogens associated with acute LRTI among children in Udupi district of south coastal Karnataka.

Material and Methods

Study setting: A cross sectional study was conducted from August 2017 to November 2017 at Department of Microbiology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, in collaboration of Dr. TMA Pai Rotary Hospital, Karkala and Manipal Centre for Virus Research, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Deemed to be University), after obtaining approval from Institutional Research and Ethical Committee (IEC-336/2017). A total of 50 children presenting with fever and cough and clinically diagnosed for acute LRTI as per Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) guidelines were admitted in paediatric ward and were enrolled for the present study. Samples were collected after obtaining the written consent from the parents of the enrolled participants.

Sample collection

Two nasopharyngeal/throat swab specimens were collected from each participant using nylon flocked swabs (COPAN, Italy) and then swabs were placed in tubes containing universal transport medium and viral transport medium. Respective nasopharyngeal swabs were transported to the laboratory maintaining cold chain.

Molecular Detection of Bacterial Aetiology

DNA was extracted from samples using a commercial kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) using manufacturer’s guidelines and Multiplex real-time PCR was performed for detection of Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae using AllplexTM Respiratory Panel 4 kit (Seegene, Seoul Korea) as per manufacturer’s guidelines.

Molecular Detection of Viral Aetiology

Total nucleic acid was extracted using MagMax kit (Ambion Inc., USA) and tested using multiplex real time PCR assay (Respiratory 21, Fast -Track Diagnostics, Luxemburg) for Influenza Virus A and B, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Adenovirus, Enterovirus, Parainfluenza Viruses 1-4, Human Coronaviruses and Human Boca virus.

Data collection

Demographic data, immunization status and history of present illness were collected by interviewing the parents of the patients. Nutritional status was assessed using weight for age National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) centile charts.

Statistical analysis

Details of the enrolled children was recorded in an excel spread sheet and statistical analysis was done using SPSS 16 (IBM, USA). Association between categorical variables was evaluated by Chi-squared test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 50 children clinically diagnosed for LRTI and hospitalized in general ward were enrolled for the present study, 30 among them were male whereas 20 were females. Median age and weight were found to be 31.5 months (Range: 4 months- 144 months) and 10kg (Range: 3.7-27.5 kg) respectively, A detailed description of demographic details and clinical findings of the enrolled children is given in Table 1.

Table 1: Details of children enrolled for the study.

| Details of children enrolled for the study | |||

| Positive for viral or bacterial aetiology

(n=34, %) |

Normal

(n=16) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI)

p value |

|

| Age, Mean (SD) in months

Range in months |

45.15 (38.18)

4-144 |

35.05 (23.04)

5-72 |

–

0.25 |

| Gender, Male

Female |

18(36)

16(32) |

12(24)

04(08) |

0.38 (0.1,1.4)

0.13 |

| Weight, Mean (SD)

Range in Kg |

12.07(6.18)

3.7-27.8 |

11.13 (4.98)

5.1-19 |

–

0.58 |

| Housing Condition, Kuccha

Pukka |

26(52)

8(16) |

15(30)

01(02) |

0.22 (0.02,1.9)

0.13 |

| Nutritional Status, Normal

Malnourished, PEM, FTT, Obese |

17(34)

17(34) |

9(18)

7(14) |

0.78 (0.24,2.57)

.67 |

| Immunization status, up to date

Due |

30(60%)

04(08) |

14(28)

02(04) |

1.07 (0.17,6.56)

0.94 |

| Fever, Present

Absent |

32(64)

02(04) |

15(30)

01(02) |

1.07 (0.09,12.71)

0.96 |

| Cough, Present

Absent |

33(66)

01(02) |

14(28)

02(04) |

4.71(0.39,56.32)

0.18 |

| Blocked runny nose, Present

Absent |

30(60)

04(08) |

13(26)

03(06) |

1.73 (0.34,8.85)

0.50 |

| Difficult Breathing, Present

Absent |

24(48)

10(20) |

13(26)

03(06) |

0.55 (0.13,2.38)

0.42 |

| Chest Indrawing, Present

Absent |

17(34)

17(34) |

12(24)

04(08) |

0.33 (0.09,1.24)

0.09 |

| X-ray findings, Normal

Suggestive of Pneumonia/Asthma |

24(48)

10(20) |

13(26)

03(06) |

0.55 (0.13,2.38)

0.42 |

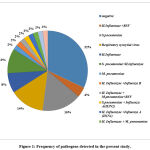

A total of 34 (68%) children were found to have infection either bacterial/ viral or mixed. S. pneumoniae was the commonest (16%; 8/50) organism, followed by Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) 14% (7/50), H. influenzae 8% (4/50) and M. pneumoniae 2% (1/50). Mixed infection was detected in 28% (14/50) of children. S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae was the most prevalent co-infection and was detected in 10% (5/50) followed by H. Influenzae and RSV (4%, 2/50) co-infection. A detailed description of the pathogen detected in the present study is given in Fig 1.

|

Figure 1: Frequency of pathogens detected in the present study. |

On analysing the aetiology among different age groups, we found that RSV (28.57%, 4/14) infection was commonly observed in children between age group 0-1 years, whereas S. pneumoniae (24.14%, 7/29) was commonest in children between 1 year to 5 years. Further, mixed infections (33.33%, 12/36) were more prevalent among children above 1 year of age. Normal duration of hospital stay was found to be 5-7 days. Recovery rate was 100% as all hospitalized children with LRTI responded well to intravenous combination of beta lactams plus amino glycoside treatment.

Discussion

Present study provides an insight into the infectious aetiology of lower respiratory tract infections among hospitalized children in Udupi district of south coastal Karnataka. Several studies in past have reported S. pneumoniae as the most common pathogen associated with LRTI in children; similar to their findings 16 % of the children in present study were also detected to have S. pneumoniae infection4-7. For PCR based diagnosis quantification of bacterial DNA load is important; a cut off value of CT ≥ 35 (≥ 8000 copies/ ml) has been described previously for distinguishing pneumococcal infection from asymptomatic colonization thus in present study a sample was considered positive only if the mean cycle threshold (CT) value was less than 358,9.

RSV is the most frequently isolated virus in infants and children worldwide in LRTI. In the present study also, RSV remained the commonest viral agent accounting for 14% cases10-12. Age dependant distribution of pathogens showed RSV (8%, 4/50) as a substantial threat in children below 1 year of age as maternal antibodies are the only means of protection during initial 6-12 months of their age13. Earlier studies have reported a gradual decrease in the prevalence of RSV with increase in age due to development of child’s own immunity against RSV; similar pattern was also seen in the present study13, 14.

Mixed infections due to respiratory pathogens are reported frequently; 28% (14/50) cases in present study were also found to have mixed infections, 12 % (6/50) among them had mixed bacterial infection. Several epidemiological studies have reported a positive correlation between colonization of S. pneumoniae and H. Influenzae, a recent study also showed increase in pneumococcal biofilm formation in presence of H. influenzae. In concordance to them 10% (5/50) cases in present study were also found to have co-infection of S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae15. A study showed that viral infection predisposes the host to bacterial infection by favouring bacterial attachment to the nasopharyngeal sites and promoting bacterial growth. 16% (8/50) cases in present study had both bacterial and viral mixed infections16, 17.

Although few Indian studies has shown significant correlation when clinical, demographic and risk factors were compared between infected and non-infected cases of acute LRTI, no such significant correlation was seen in present study18,19. The possible reason for discrepancy might be the low sample size in the present study which is one of the major limitations of this study. Further the prevalence of bacterial and viral pathogens majorly depends on the geographical area, seasonal variations and the pathogen panel included for PCR. Though we have included major pathogens responsible for acute LRTI among paediatric age group discrepancies may arise. Despite above limitations the present study provides important baseline information on aetiology of acute LRTI among paediatric population in Udupi district of south coastal Karnataka which can be useful for future researchers in formulating strategies for larger surveys or management in this region.

Conclusion

S. pneumoniae and RSV were the most predominant bacterial and viral pathogens respectively associated with LRTI among paediatric population in present study. Further we found very high number of cases with mixed infections which signifies the urgent need of much elaborate studies for elucidating the clinical significance of these infections as well as for better understanding of epidemiology of LRTI among children in this region.

Acknowledgment

Authors would like to acknowledge all the technical staff of Department of Microbiology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Dr. TMA Pai Rotary Hospital, Karkala for their contributions and support in the current study.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

This study was partially supported by the ICMR grant No. 5/8/7/15/2010-ECD-I of Dr Arun Kumar Govindakarnavar.

References

- Krishnan A, Kumar R, Broor S, Gopal G, Saha S, Amarchand R, Choudekar A, Purkayastha D.R, Whitaker B, Pandey B, Narayan VV. Epidemiology of viral acute lower respiratory infections in a community-based cohort of rural north Indian children. J Glob health, 2019; 9(1). doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.010433

CrossRef - Richter J, Panayiotou C, Tryfonos C, Koptides D, Koliou M, Kalogirou N, Georgiou E, Christodoulou C. Aetiology of acute respiratory tract infections in hospitalised children in cyprus. PloS one, 2016 ;13;11(1): e0147041. doi: 1371/journal.pone.0147041

CrossRef - Aydemir O, Aydemir Y, Ozdemir M. The role of multiplex PCR test in identification of bacterial pathogens in lower respiratory tract infections. Pak J Med Sci, 2014; 30(5):1011–1016. doi: 12669/pjms.305.5098

CrossRef - Capoor MR, Nair D, Aggarwal P, Gupta B. Rapid diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia using the Bac T/alert 3D system. Braz J Infect Dis, 2006; 10:352–356. doi: 1590/s1413-86702006000500010

CrossRef - Farooqui H, Jit M, Heymann DL, Zodpey S. Burden of severe pneumonia, pneumococcal pneumonia and pneumonia deaths in Indian states: modelling based estimates. PLoS ONE, 2015; 10: e0129191. doi: 1371/journal.pone.0129191

CrossRef - Rudan I, O’Brien KL, Nair H. e Liu L, Theodoratou E, Qazi S, et al. Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia in 2010: estimate of incidence, severe morbidity, mortality, underlying risk factors and causative pathogens for 192 countries. J Global Health, 2013; 3:10401. doi: 7189/jogh.03.010401

- Mathew JL, Singhi S, Ray P, Hagel E, Saghafian–Hedengren S, Bansal A, Ygberg S, Sodhi KS, Kumar BR, Nilsson A. Etiology of community acquired pneumonia among children in India: prospective, cohort study. J Global Health, 2015; 5:1–9. doi: 7189/jogh.05.020418

CrossRef - Collins AM, Johnstone CM, Gritzfeld JF, Banyard A, Hancock CA, Wright AD, Macfarlane L, Ferreira DM, Gordon SB. Pneumococcal Colonization Rates in Patients Admitted to a United Kingdom Hospital with Lower Respiratory Tract Infection: a Prospective Case-Control Study. J Clin. Microbiol, 2016; 54(4):944-949. doi: 1128/jcm.02008-15

CrossRef - Albrich WC, Madhi SA, Adrian PV, Van Niekerk N, Mareletsi T, Cutland C, Wong M, Khoosal M, Karstaedt A, Zhao P, Deatly A. Use of a rapid test of pneumococcal colonization density to diagnose pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis, 2012; 54(5):601-609. doi: 1093/cid/cir859

CrossRef - Arden KE, McErlean P, Nissen MD, Sloots TP, Mackay IM. Frequent detection of human rhinoviruses, paramyxoviruses, coronaviruses, and bocavirus during acute respiratory tract infections. J Med Virol, 2006; 78(9):1232-1240. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20689.

CrossRef - Wong S, Pabbaraju K, Pang XL, Lee BE, Fox JD. Detection of a broad range of human adenoviruses in respiratory tract samples using a sensitive multiplex real time PCR assay. J Med Virol, 2008, 80(5):856-865. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21136.

CrossRef - Castro‐Rodriguez JA, Daszenies C, Garcia M, Meyer R, Gonzales R. Adenovirus pneumonia in infants and factors for developing bronchiolitis obliterans: a 5-year follow-up. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2006, 41(10):947-953. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20472

CrossRef - Niewiesk S. Maternal Antibodies: Clinical Significance, Mechanism of Interference with Immune Responses, and Possible Vaccination Strategies. Front Immunol, 2014; 5:446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00446.

CrossRef - Khadadah M, Essa S, Higazi Z, Behbehani N, Al‐Nakib W. Respiratory syncytial virus and human rhinoviruses are the major causes of severe lower respiratory tract infections in Kuwait. J Med Virol, 2010; 82:1462–1467. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21823.

CrossRef - Richter J, Panayiotou C, Tryfonos C, Koptides D, Koliou M, Kalogirou N, Georgiou E, Christodoulou C. Aetiology of Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Hospitalised Children in Cyprus. PLoS ONE, 2016; 11 (1): e0147041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147041.

CrossRef - Wolter N, Tempia S, Cohen C, Madhi SA, Venter M, Moyes J, Walaza S, Malope-Kgokong B, Groome M, du Plessis M, Magomani V. High nasopharyngeal pneumococcal density, increased by viral co-infection, is associated with invasive pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis, 2014; 210: 1649–1657. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu326.

CrossRef - Serin DÇ, Pullukçu H, Çiçek C, Sipahi OR, Taşbakan S, Atalay S. Bacterial and viral etiology in hospitalized community acquired pneumonia with molecular methods and clinical evaluation. J. Infect Dev Ctries, 2014; 8(04):510-518. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3560.

CrossRef - Singh AK, Jain A, Jain B, Singh KP, Dangi T, Mohan M, Dwivedi M, Kumar R, Kushwaha RA, Singh JV, Mishra AC. “Viral aetiology of acute lower respiratory tract illness in hospitalised paediatric patients of a tertiary hospital: one-year prospective study,” Indian J Med Microbiol, 2014; 32: 13–18. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.124288.

CrossRef - Bharaj P, Sullender WM, Kabra SK, Mani K, Cherian J, Tyagi V, Chahar HS, Kaushik S, Dar L, Broor S. “Respiratory viral infections detected by multiplex PCR among pediatric patients with lower respiratory tract infections seen at an urban hospital in Delhi from 2005 to 2007,” Virol J, 2009; 6, 89. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-89.

CrossRef