Patricia-Elizabeth Cossío-Torres1 , Aldanely Padrón-Salas*1

, Aldanely Padrón-Salas*1 , Anuradha Sathiyaseelan2

, Anuradha Sathiyaseelan2 , Manuel Soria-Orozco1

, Manuel Soria-Orozco1 and Amado Nieto-Caraveo1

and Amado Nieto-Caraveo1

1Department of Public Health, Autonomous University of San Luis Potosi, San Luis Potosí, 78210, Mexico.

2Department of Psychology, Christ University, Bangalore, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: aldanely.padron@gmail.com

DOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1706

Abstract

There is a tremendous global increase in the older adults’ population. Mental health in older age is as important in as it is for other age categories. Majority of older adults show healthy states, vitality, good humor and enthusiasm in performing various activities, interest in continuing to contribute to their family and society despite the difficulties of this stage of life due to large part to resilience they have. The aim of the study was to establish social and psychosocial factors associated with resilience. A cross-sectional and correlation study was conducted on older adults who were hospitalized in a public General Hospital of Mexico in 2013. Resilience, gender, occupation, family environment, self-esteem, presence of critical life events, and the presence of significant persons were assessed. 186 older adults participated. Higher levels of resilience were found in males and employed people. Participants with a functional family and high self-esteem had the highest levels of resilience. Besides, 15% of the variance of the total resilience score was explained by family environment, and 27% was explained by self-esteem (p<0.05). Although all participants were older adults, individual characteristics such as gender, occupation and self-esteem; besides family environment, were found to be associated to the levels of resilience in this population. Specific programs- -enhancing these factors are needed to improve resilience.

Keywords

Critical Events; Family; Older Adults; Resilience; Self-Esteem; Significant Persons

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Cossío-Torres P, Padrón-Salas A, Sathiyaseelan A, Soria-Orozco M, Nieto-Caraveo A. Psychosocial Correlates of Resilience Among Older Adults in Mexico. Biomed Pharmacol J 2019;12(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Cossío-Torres P, Padrón-Salas A, Sathiyaseelan A, Soria-Orozco M, Nieto-Caraveo A. Psychosocial Correlates of Resilience Among Older Adults in Mexico. Biomed Pharmacol J 2019;12(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/2HMe9xZ |

Introduction

Mexico is going through a process of demographic and epidemiologic transition, influenced by major changes in birth and death rates. In 2012, the National Institute of Statistics and Geography reported that the population over 60 years old represented 9.2 percent of the total population in Mexico and it is estimated that, by 2050 older adults will constitute about 28 percent of the national population.1,2 In 2010, 22.6 percent of the population over 60 years of age in Mexico did not have social security, including health services, however, they had the option of going to public hospitals that were paid by the government through a health service called “Seguro Popular” that only covered a catalogue of diseases and if an older adult got a disease that was not in the catalogue, they had to pay for health services which in turn created health disparities.3

Old age is a period of gradual adaptive challenges brought on by the changing physical and mental conditions along with the difficulties in the development of daily and social activities.4 Over the years, the natural wear and tear of the body, genetics, and lifestyle cause issues in the health of older adults, which make them more likely to be hospitalized, and puts them in a situation of vulnerability as a result.5,6

When it comes to mental health issues, older adult experience the same factors as other adults, but along with that they may be experiencing issues related to decline in functional ability such as restricted mobility, chronic pain, and fear of health issues. Added to that, there are other causes such as socio economic conditions and bereavement of loved ones and loneliness.

There are individuals who are able to withstand stress, tolerate pressure under conflict, violence or vulnerable situations, and face all by doing strategies that help them overcome adversities or even emerge stronger; these social and personal processes are known as resilience.7

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines resilience as a process of adapting and bouncing back to life from difficult experience. Resilience is a capacity to bounce back to normalcy and it is a capacity to face difficult situations during the changes in life. We could also say resilience is the individual, family or community capacity to develop processes to cope, adapt and thrive in adverse situations. The term was adapted to social sciences to characterize those who, despite being born and living in high-risk situations, face those circumstances and further strengthen from them, which not only means the reintegration of the person after adversity, but also includes a subsequent growth.8,9

There are characteristics that appear more frequently in those who have demonstrated resilience conditions that are part of the personality and perspective of life that each person has, and they constitute a basis from which the environmental and social factors act. These are: insight, morality, independence, relationships, initiative, humor and creativity (called the pillars of resilience), all supported by self-esteem. The most significant environmental and social factors are: family, friends, couple, occupation, critical life events, presence of a significant person as support, professional support, poverty level and others.8,9

A high level of resilience has shown to have a positive influence on health indicators, such as biochemical parameters, mental health and quality of life of older hospitalized adults that could result in the reduction of the number and duration of hospitalizations which in turn, could reduce the situation of vulnerability to which they are exposed to when they are hospitalized.11,12,13 High resilience has also been significantly associated with positive outcomes, including successful aging, lower depression, and longevity.14

Research in resilience allows going beyond a risk approach because it is possible to determine those protective factors that allow the person to cope with the adversities of life. Therefore, the identification of factors associated with a resilient personality translates into planning strategies and health policies that could ensure a better quality of life and success of health programs tailored to older adults, especially when they live alone, or they have to do everything by themselves.15

There is no universally agreed definition or measure of resilience and, partly as a result, there are wide variations in the measured prevalence of resilience and factors that are associated with resilience. However, there are three main methods for measuring resilience: measuring adversity, successful adaptation, and process. In this study, the measurement of resilience included only the measurement of adversity and process.16

This study was conducted to establish the psychosocial factors (gender, occupation, family environment, self-esteem, presence of critical life events, and presence of significant people) associated to resilience characteristics: Total Resilience, Strength and Self Confidence (independence and initiative, pillars of resilience), Social Competence (relationship, pillar of resilience), Family Support (environmental factor of resilience), Structure (creativity, pillar of resilience) and Social Support (environmental factor of resilience) among older adults hospitalized in a General Hospital of Mexico.

Materials and Method

A cross-sectional and correlation study was carried out from May to September 2013 (due to hospital permission) in a Public General Hospital of Mexico that has 250 hospital beds and is considered as a reference center for the north central region of the country. This hospital works with funding from Seguro Popular that is financed by government through taxes.

The study included hospitalized patients between 60 and 80 years of age. Patients who refused to participate were excluded from the study along with outpatients who were diagnosed with Delirium, Dementia and / or cognitive impairment.

The questionnaires were filled in by the patients and the interviews took place on the day when they arrived to the hospital or the day after, but they were always applied before a surgery if they needed it.

The study was approved by the Committee of Research and Ethics of the Hospital under the registration number 37-13. The written informed consents from the patients were appropriately obtained.

Tools

Socio-demographic variables were measured using a questionnaire created for this study (age, gender, civil status, education and occupation). Furthermore, three questions were asked in order to determine the presence of a significant person in the life of the older adult: under happy, sad, and problem circumstances.

The Resilience (RESI-M) questionnaire contains five dimensions: strength and self-confidence (score 19 to 76), social competence (score 8 to 32), family support (score 6 to 24), social support (score 5 to 20) and structure (score 5 to 20); the total resilience score includes all of them, with a minimum of 43 and maximum of 172 points. The instrument consists of 43 items, and highlights features of resilient personalities in different levels (individual, family and society) and divides them into five dimensions (Strength and self-confidence, social competence, family support, social support and structure).16

The family APGAR scale assesses family function through five components: adaptation, partnership, growth, affection and problem resolution.17

The Rosenberg self-esteem scale consists of 10 items and focuses on the feelings of self-respect and self-acceptance.18

The Thomas Holmes Critical Events Scale gives a certain value to events that cause stress.19

All the instruments that were applied were validated for Mexico population, the Cronbach’s Alpha for the APGAR Scale was 0.825 and for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was 0.687. For the Resilience Questionnaire, the Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.922 to 0.974 for each dimension.

Socio-demographic and psychosocial aspects were described in proportions as descriptive analysis. For the bivariate analysis, occupation and significant others were converted into binary variables in order to evaluate the mean differences between them and the different resilience dimensions; Mann-Whitney U Test and Kruskall-Wallis Test were used. The construction of multiple linear regression models was not possible because of multicollinearity among the variables that had a significant association in the bivariate analysis, so simple linear regression was used for the total resilience score instead. The V.11 statistical package STATA ® and SPSS version 21 statistics were used.

Results

Socio Demographic Descriptions

The data of total 186 hospitalized older adults are depicted in table 1, 11.20 % of which answered the instruments on the same day of admission and 88.30 % of them on the day after. The mean age was 68.1 years (Standard deviation: 5.83 years). The top three diagnoses upon admission were Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy ranked first with 11.8%, followed by Diabetes Mellitus and its complications with 11.2%, and in third place Postoperative Cholecystectomy with 6.4%. The total number of diagnoses on admission was 67 (data not shown). Half of the participants were males, 60.2% were married or in free union, 2.7% had a technical career or university degree, 37.6% were employed and 5.4% of them were in moderate poverty Table 1.

Table 1: Socio-demographic Aspects.

| Socio-demographic data | Frequency (n=186) | Percent (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 93 | 50.0 |

| Female | 93 | 50.0 | |

| Civil Status | Single | 25 | 13.4 |

| Married-consensual union | 112 | 60.2 | |

| Divorced-Widowers | 49 | 26.3 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 45 | 24.2 |

| Read and write | 8 | 4.3 | |

| Incomplete elementary school | 86 | 46.3 | |

| Complete elementary school | 22 | 11.8 | |

| Middle school | 16 | 8.6 | |

| High school | 4 | 2.1 | |

| Technical career | 3 | 1.6 | |

| University Degree | 2 | 1.1 | |

| Occupation | Currently unemployed | 116 | 62.4 |

| Employed | 70 | 37.6 | |

| Simplified poverty index | No evidence of family poverty | 25 | 13.4 |

| Low family poverty | 151 | 81.2 | |

| Moderate family poverty | 10 | 5.4 | |

Psychosocial Aspects

Table 2, shows the psycho social aspects. Only 37.1 % of participants had a functional family, the rest had some degree of family dysfunction. According to the scores on the Self-esteem scale, 42% of participants had a high self-esteem. 61.9 % had no major problems according to the scale of critical events. The most prevalent significant person was the partner, followed by the adult children. Nevertheless, about 15% of older adults did not share their happiness, sadness or problems with anyone.

Table 2: Psychosocial aspects.

| Psychosocial Data | Frequency (n=186) | Percent (%) | |

| Family Environment | Functional family | 69 | 37.1 |

| Mild dysfunction | 70 | 37.6 | |

| Moderate dysfunction | 29 | 15.6 | |

| Severe dysfunction | 18 | 9.7 | |

| Self-esteem | Low self-esteem | 53 | 28.5 |

| Moderate self-esteem | 55 | 29.5 | |

| High self-esteem | 78 | 42.0 | |

| Critical events | No major issues | 115 | 61.9 |

| Mild critical events | 54 | 29.0 | |

| Moderate critical events | 17 | 9.1 | |

| Significant person: happiness | Partner | 71 | 38.2 |

| Adult Children | 61 | 32.8 | |

| Otherϯ | 27 | 14.5 | |

| None | 27 | 14.5 | |

| Significant person: problems | Partner | 66 | 35.5 |

| Adult Children | 63 | 33.9 | |

| Otherϯ | 28 | 15.0 | |

| None | 29 | 15.6 | |

| Significant person: sadness | Partner | 65 | 35.0 |

| Adult Children | 62 | 33.3 | |

| Otherϯ | 28 | 15.0 | |

| None | 31 | 16.7 | |

Others include: friend, siblings, grandchild, nephews, mother, priest, sister-in-law.

The mean value of resilience was 136.9, the minimum was 60 and the maximum was 170 is shown in table 3. Statistically significant differences were found in the bivariate analysis between males and females in Strength and Self-Confidence, Structure and Total Resilience, with higher levels of resilience among male patients. Employed older adults had higher levels of Strength and Self-Confidence in comparison to those who were currently unemployed (p<0.05). There were statistically significant differences between all categories of family environment and functional family was found to have the highest levels of resilience, except for the structure dimension. Participants with a high self-esteem had the highest levels of resilience in all the dimensions, in contrast to participants with a low self-esteem who had the lowest levels of resilience (p<0.05) Table 3.

Table 3: Mean rank differences among the Total Resilience Scale and its dimensions with social and psychosocial factors.

| Factors | Characteristics | Total Resilience | Strength and self-confidence | Social competence | Family support | Social support | Structure | |

| n | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | ||

| Gender | Female | 93 | 88.5* | 85.9* | 86.4 | 95.3 | 93.6 | 88.5* |

| Male | 93 | 98.4* | 101* | 100.5 | 91.6 | 93.4 | 90.4* | |

| Occupation | Employed | 70 | 101.5 | 103.7* | 102.1 | 91.9 | 94.6 | 95 |

| Currently unemployed | 116 | 88.6 | 87.3* | 88.2 | 94.4 | 92.7 | 92.5 | |

| Family environment | Severe dysfunction | 18 | 51.1⁑ | 61.2⁑ | 62.8⁑ | 37.3⁑ | 52.8⁑ | 98 |

| Moderate dysfunction | 29 | 77.9⁑ | 80.7⁑ | 88.2⁑ | 79.5⁑ | 78.8⁑ | 81.5 | |

| Mild dysfunction | 70 | 89.6⁑ | 89.2⁑ | 91.4⁑ | 93.8⁑ | 86.6⁑ | 88.6 | |

| Functional family | 69 | 114.9⁑ | 111.6⁑ | 105.8⁑ | 113.7⁑ | 117.2⁑ | 102.3 | |

| Self-esteem | Low self-esteem | 53 | 60.5⁑ | 63.8⁑ | 72.9⁑ | 79.3⁑ | 72.6⁑ | 66.7⁑ |

| Moderate self-esteem | 55 | 84.3⁑ | 79.4⁑ | 87.9⁑ | 83.1⁑ | 95.8⁑ | 95.5⁑ | |

| High self-esteem | 78 | 122.2⁑ | 123.5⁑ | 111.3⁑ | 110.3⁑ | 106⁑ | 110.2⁑ | |

| Critical events

|

No major issues | 115 | 94.6 | 96 | 90.9 | 92 | 93.9 | 96.5 |

| Mild critical events | 54 | 88.4 | 85.7 | 93 | 97.9 | 93.5 | 86.8 | |

| Moderate critical events | 17 | 101.9 | 101.2 | 112.1 | 89.4 | 90.1 | 94.1 | |

| Significant person: happiness | Partner, adult children and others | 159 | 94 | 93.2 | 94 | 95.2 | 93.9 | 92.3 |

| None | 27 | 90 | 95 | 90 | 83.1 | 91 | 100 | |

| Significant person: problems | Partner, adult children and others | 157 | 95 | 94 | 95 | 94.5 | 94.5 | 92.4 |

| None | 29 | 85.3 | 90.3 | 85.2 | 87.5 | 87.5 | 99.1 | |

| Significant person: sadness | Partner, adult children and others | 155 | 95.5 | 93.9 | 95.7 | 96.1 | 95.1 | 92.8 |

| None | 31 | 83.4 | 91.1 | 82.1 | 80.3 | 85.1 | 96.9 | |

*p<0.05. Mann-Whitney U Test,⁑p<0.05. Kruskall-Wallis Test.

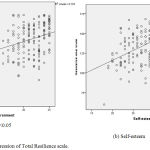

15% of the variance in the total resilience score was explained by family environment and 27% were explained by self-esteem Figure 1.

|

Figure 1: Simple Linear Regression of Total Resilience scale.

|

Discussion

This study focused on finding the relationship between psychosocial factors and resilience among older adults in Mexico. The previous section on results describes the socio demographic characteristics of the sample.

Resilience was found to be high among the participants, specifically males had higher levels of resilience. A study evaluated the socio-demographic characteristics and found that individuals who were occupationally active had a considerable number of reasons to feel emotionally satisfied.12

In this study, men and employed people were found to have higher levels of resilience. However the national data3 shows the employment rates are the same for men and women in Mexico, which is a unique finding from this study.

Most participants in this study had a high self-esteem (56% of participants), which is consistent with another study where 51% of participants had a high self-esteem and an adequate social functioning.20

It has been found that older adults with positive self-esteem consider themselves healthy despite being exposed to adverse conditions such as diseases.21,22

It is noteworthy that while analyzing the relationship between resilience and self-esteem, it appeared that those with high self-esteem had high resilience, which allowed us to affirm that self-esteem is one of the most important pillars of resilience. Thus, self-esteem is one of the most important psychological elements in the care of older adults and requires daily strengthening.20 Besides, self-esteem is a strong factor for the development of resilience as confirmed by studies.23, 24, 25, 26

When the older adults are having high self esteem, it increases their bouncing back capacity even during critical times in their life.

A study done in Cuba in 1998 assessed family functioning using the APGAR scale, and found that 33% of older adults had functional families.27 Family and other community systems can be seen as the context that nourishes and strengthens resilience in individuals.28 This study confirms that along with high self-esteem; adequate family environment is associated with high resilience (p < 0.001).

The presence of a significant person in the lives of older adults is of paramount importance, as it constitutes part of their family and social support. The literature supports the fact that partners are an important source of resilience against health and disability problems.8 In fact it was found that the partners, followed by the sons and daughters were the most important people for hospitalized older adults, but this variable was not associated with resilience (p>0.05) in this present study.

The presence of resilience among older adults is conceptualized as maintaining physical and psychological health despite threats and risks. However, this is not possible for all people, because the health process is multifactorial. For others, it is the challenge of maintaining stability despite the loss of a job, a loved one, or health. Thus, older people who have the ability to use personal resources and environmental factors as social support (in community, family, and professional sector) are more likely to be resilient, whether they are healthy or not.25

Conclusion

This study established that the psychosocial factors such as gender, occupation, family environment and self-esteem were associated with the levels of resilience in Mexican older adults. Self-esteem was the strongest factor associated. These findings should be considered in the design of local health programs for this specific population to improve their abilities to cope with adversities and foster the presence of resilience.

The government should opt for the creation of sustainable holistic programs by maintaining or enhancing social support and facilitating access to care and resources in order to promote resilience among older adults. Developing strategies and public policies aimed at improving the psychosocial status of older adults such as their self esteem as well as an adequate social network seem to be necessary. Training on ‘Integrating mindfulness’29 could also increases self esteem and resilience. The above could ensure better achievements in health programs as well as promote prevention, improve adherence to treatments and result in a dignified and better quality of life. Therefore, resilience among older adults should be seen as an opportunity for successful and dignified aging.

Limitations

There is no universally agreed measure of resilience and, partly as a result, there are wide variations in the measured prevalence of resilience as well as variations in the findings of factors that are associated with resilience. Consequently, it is very difficult to compare the results with that of other studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Saira Diaz for her dedication and efforts in getting the permissions to make this project possible. The authors wish Ms.Soumya R for her support in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding Source

This work was supported by the funding provided by the Faculty Improvement Program (PROMEP) of the Ministry of Public Education of Mexico, under the Grant PROMEP/103.5/12/3953.

Statement of Informed Consent

This study had done in agreement with the statement of informed consent.

Ethics of Human and Animal Experimentation

The study was approved by the Committee of Research and Ethics of the Hospital under the registration number 37-13. The written informed consents from the patients were appropriately obtained.

References

- Perfil sociodemográfico de adultos mayores. Mexico: INEGI. 2010. [cited 2016 Jul 20]. Available from: http://internet.contenidos.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/censos/poblacion/2010/perfil_socio/adultos/702825056643.pdf

- México en Cifras. Información Nacional, por Entidad Federativa y Municipios [cited 2013 Jul 16]. Available from: http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/mexicocifras/default.aspx

- “Estadísticas a propósito del…día internacional de las personas de edad (1 de octubre).” [cited 2016 Sept 28]. Available from: http://www.inegi.org.mx/saladeprensa/aproposito/2014/adultos0.pdf

- Gasparin L., Alejo J., Haimovich F., Olivieri S. and Tornarolli L. Poverty among older people in Latin America and the Caribbean. Journal of International Development. 2009; 22 (2): 176-207.

- Arrebola-Morenoa, A. L., Garcia-Retamero, R., Catenab, A., Marfil-Álvareza, R., Melgares-Morenoa, R. and Ramírez-Hernándeza, J. A. On the protective effect of resilience in patients with acute coronary syndrome. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology.2014; 14(2): 111-119.

- Christensen, K., Doblhammer, G., Rau, R. and Vaupel, J. W. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. The Lancet. 2009; 349 (9and96): 1196-1208.

- Herrman, Stewart, H., Diaz-Granados, D. E., Berger, N., Jackson, E. L., Yuen, B. and Tracy. What Is Resilience? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011; 56: 258-265.

- Wallhagen, M. I., Strawbridge, W. J., Shema, S. J. and Kaplan, G. A. Impact of Self-Assessed Hearing Loss on a Spouse: A Longitudinal Analysis of Couples. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2004; 59(3): S190–S196.

- Wiles, J. L., Wild, K., Kerse, N. and Allen, R. E. Resilience from the point of view of older people: ‘There’s still life beyond a funny knee’. Social Science and Medicine. 2012; 79(3): 416-424.

- Mosqueiro, B. P., Rocha, N. S. and Fleck, M. P. Intrinsic religiosity, resilience, quality of life, and suicide risk in depressed inpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015; 179: 128-133.

- Sarubin, N., Wolf, M., Giegling, I., Hilbert, S., Naumann, F., Gutt, D., Jobst A., SabaB L., Falkai P., Rujescu D., Bühner M. and Padberg, F. Neuroticism and extraversion as mediators between positive/negative life events and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015; 82: 193-198.

- Manuel, T. J., Patricia, S., Carlo, M. J. and Teresa, M. Resilience and coping as predictors of general well-being in the elderly: A structural equation modeling approach. Aging and Mental Health. 2012; 16(3): 317-326.

- Hao, S., Hong, W., Xu, H., Zhou, L. and Xie, Z. Relationship between resilience, stress and burnout among civil servants in Beijing, China: Mediating and moderating effect analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015; 83: 65-71.

- MacLeod, S., Musich, S., Hawkins, K., Alsgaard, K. and Wicker, E. R. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing. 2016; 37(4): 266-272.

- Hildon, Z., Smith, G., Netuveli, G. and Blane, D. Understanding adversity and resilience at older ages. Sociology of health & Illness. 2008; 30(5): 726-740.

- Lever, J. P. and Valdez, Y. N. Desarrollo de una escala de medición de la resiliencia con mexicanos (RESI-M). Interdisciplinaria. 2010; 27(1): 7-22.

- Gabriel, S. (1978). The Family APGAR: A proposal for family function test and its use by physicians. Journal of Family Practice. 1978; 6(6): 1231-1239.

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Science. 1965; 148 (3671): 804.

- Holmes, T. H. and Rahe, R. H. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967; 11(2): 213–218.

- Zavala G., Vidal D., Castro M., Quiroga P. and Klassen G. Funcionamiento Social Del Adulto Mayor Social Functioning Of Elderly. Ciencia y Enfermería. 2006; XII (2): 53-62.

- Collins, A. L. and Smyer, M. A. The Resilience of Self-Esteem in Late Adulthood. Journal of aging and health. 2005: 471-489.

- Gallacher, J., Mitchell, C., Heslop, L. and Christopher, G. (2012). Resilience to health related adversity in older people. Quality in Ageing and older adults. 2012; 13(3): 197-204.

- Lamond A.J., Depp C.A., Allison M., Langer R., Reichstadt, J., Moore D.J. and Jeste D.V. Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling older women. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008; 43: 148-154.

- Windle G., Markland DA and Woods RT. Examination of a theoretical model of psychological resilience in older age. Journal of Aging and Mental Health. 2007; 12: 285-292.

- Mehta M., Whyte E., Lenze E., Hardy S., Roumani Y., Subashan P and Studenski S. Depressive symptoms in late life: associations with apathy, resilience and disability vary between young‐old and old‐old. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.2008; 23: 238-243.

- Gooding P.A., Hurst A., Johnson J. and Tarrier N. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.2011; 27: 262-270.

- Díaz O., Soler M. and García M. The family APGAR in cohabiting elderly. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral. 1998; 14: 548-553.

- Adams K., Sanders S. and Auth E. Loneliness and depression in independent living retirement communities: risk and resilience factors. Aging and Mental Health. 2004; 4: 475-485.

- Sathiyaseelan A. and Sathiyaseelan B. Integrating ‘mindful living’ for a peaceful life. Research journal of social science and management. 2014; 4: 189-192.